The man dubbed the Balkan 'Cocaine King' was depicted in regional media as the brain behind one of the largest and most successful drug-smuggling operations ever recorded in the region since his name first surfaced in connection with a massive cocaine seizure in 2009.

He and several of his alleged associates also stand accused of laundering about € 22 million (more than US$ 23 million), the profits from years of smuggling operations. Some of the 18 people who were indicted along with him signed plea agreements.

The elusive drug lord operated under the eyes of law enforcement in several countries for years, and his success was partly due to strong connections he had with several powerful Serbian and Montenegrin businessmen and officials.

In July 2015, Saric was sentenced to a 20-year prison term for cocaine smuggling, which he has appealed.

His long-running money laundering trial (it began in 2011) is, however, still ongoing.

Saric stood before the court to face his money laundering accusations again in a hearing on Jan. 14, 2016. This is the second time the money laundering trial has restarted, due to administrative reasons within the Serbian justice system.

The Cocaine Cartel Surfaces

In October 2009, law enforcement in Uruguay seized more than two tons of cocaine from a British-flagged yacht named "Maui " in the port of Santiago Vasquez, west of Montevideo, Uruguay's capital. Two people were arrested - one Uruguayan and one Croatian national.

The two were part of a group trying to transfer the cocaine from the yacht to a larger ship which was set to arrive in western Europe. However, the cargo was intercepted as part of a police operation code-named "The Balkan Warrior" – a long-running joint operation between the US Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA), the Serbian Intelligence Agency (BIA), and police in Uruguay and Argentina.

Three people accused of involvement with the smuggling operation were arrested the same day, and a series of additional arrests followed across Serbia. Some of the suspects were convicted criminals previously known to authorities.

One of the first three to be arrested was Zeljko Vujanovic, who was picked up at a nightclub called "Casino" that he managed. The club was owned by Saric, his cousin.

Enter: Darko Saric

Soon, Saric would be named as the mastermind behind a powerful Balkan organized crime group which smuggled huge quantities of cocaine into the European drug market between 2006 and 2009 from South American countries such as Brazil, Argentina and Uruguay.

The drugs were transported from the east coast of South America to Italy, Spain, Greece and other countries in Western Europe.

Although he owned real estate, cafes, nightclubs, restaurants and multiple companies in Serbia, Saric was not very well known to the public. Investigators say they knew about his involvement in the drug trade since 2005, but that no investigation against him was initiated until 2008.

Slobodan Homen, the former Secretary to the Serbian Ministry of Justice, said Saric's group amassed billions of dollars in the course of its operations.

Saric went into hiding following the seizure in Uruguay, and in January 2010, Serbia issued an international arrest warrant for him. Between 2010 and 2012, prosecutors filed eight indictments against him, accusing him of money laundering and organizing the smuggling of 5.7 tons of cocaine.

Saric was on the run for four years until March 2014, when he turned himself in voluntarily.  Darko Saric

Darko Saric

According to Justice Minister Nikola Selakovic, Saric caught wind that Serbian authorities were hot on his trail and decided to surrender to avoid a possible bloodbath. However, Saric was believed to be in talks with the government for some time before surrendering.

During his drug-smuggling trial, Saric maintained the charges were politically motivated, as the former Serbian government wanted him to testify against Montenegro, where documentation obtained by the OCCRP reveals he was a top depositor in the First Bank of Montenegro, which is controlled by the family of Montenegrin Prime Minister Milo Djukanovic. He also got loans on very good terms from the Prime Minister's family bank.

Nevertheless, he was convicted of cocaine smuggling and sentenced to 20 years in prison on July 13, 2015. A number of his associates were also sentenced to long terms; some, who are still on the run, were sentenced in absentia. He is currently appealing his sentence. In Serbia politicians, businessmen and drug dealers often get significant reductions of their sentences during the appeal process.

Money laundering?

Prosecutors believe Saric and his associates laundered the proceeds from their drug smuggling operations by buying shares in an array of Serbian companies.

One of the three money laundering indictments describes a plan the group allegedly devised in order to invest €280,000 (US$308,000) of drug money into purchasing 70 percent of shares in the state company "Bratstvo". The plan included a strategy to hide the real buyers of the shares. Prosecutors say one of the suspects would bring a large bag of drug money to a local bank, along with a number of IDs of various people. The bank would open bank accounts for those people, and the suspects would deposit portions of the dirty money into those accounts.

The money from those accounts would subsequently be paid to the company that, in collusion with another company, would later privatize Bratstvo.

These amounts never exceeded €15,000 (US$16,500), the amount above which banks must report transactions to the Administration for the Prevention of Money Laundering.

According to OCCRP and KRIK, a list of Saric's companies shows he laundered money by privatizing hotels in Serbia and buying companies and property from people who were either charged with or convicted of involvement in organized crime.

He controlled an array of companies in Serbia and Montenegro which were involved in various activities, from media and construction to kindergartens and nightclubs.

In 2010, Saric sent a letter to prosecutors saying he was a legitimate businessman who had acquired his money legally. In the letter, Saric explains that he earned € 30 million (US$ 33 million) just from his sale of Serbia's leading distribution company, Stampa Sistem, to a German media concern.

What the letter did not include, however, is Saric's explanation of how he acquired Stampa Sistem in the first place.

His money-laundering trial began in February 2011, and has been re-started twice since then.

The first time the trial was stalled was in March 2012, when one of the judges presiding over the case, Nada Zec, was swapped with judge Aleksandar Tresnjev.

Now, according to KRIK, the same thing has happened again.

Judge Vladimir Vucinic, who had presided over the case for five years, was transferred to serve at another department within the Serbian High Court as of Jan. 1, 2016.

The High Court of Serbia said it made the decision because Vucinic's mandate serving in the Organized Crime Department had expired.

However KRIK reports that Vucinic told the newspaper "Politika" that he has doubts about the decision. He said that all judges that were in the Special Department for Organized Crime had their mandates extended except for him.

He will be replaced by Judge Dragomir Gerasimovic.

However, according to KRIK, these developments should not delay the trial. The court will not hear the defendant's testimonies, nor will the evidence against Saric and his associates be presented anew.

Saric – How the Balkan Cocaine Cartel Conquered EuropeKRIK reports that at the start of the trial on Jan. 14, Saric said, "I stand by what I said before. I have nothing to add or subtract."

Saric – How the Balkan Cocaine Cartel Conquered EuropeKRIK reports that at the start of the trial on Jan. 14, Saric said, "I stand by what I said before. I have nothing to add or subtract."

Whether he will ultimately face a long prison sentence is still unclear. Since the government of Prime Minister Aleksandar Vucic took over in 2014, some of the judges, prosecutors, police and intelligence agents responsible for Balkan Warrior and other prosecutions of organized crime have been fired, reassigned or retired.

International law enforcement officials say Serbia is no longer cooperating effectively on organized crime investigations. In Serbia, where justice has a political component, Saric's ultimate term may be more dependent on political manuevering behind the scenes.

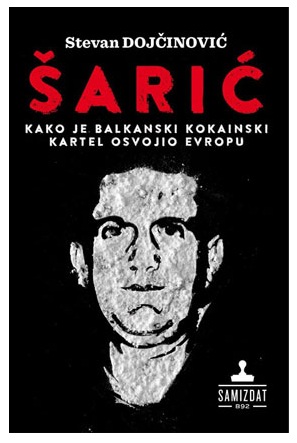

Editors Note: Saric's rise from a young man stealing salami to the very top of the Balkan cocaine cartel, worthy of a Hollywood movie script, is described by KRIK chief editor Stevan Dojcinovic in his book "Saric – How the Balkan Cocaine Cartel Conquered Europe".