The newly frozen assets appear to include upscale London real estate and Wall Street apartments, according to analysis of property records and a leaked French investigation file obtained by reporters.

The United States, Canada, and the United Kingdom imposed the latest sanctions on Salame and his associates on Aug. 10, shortly after the 73-year-old stepped down from his 30-year tenure at the Banque du Liban (BdL) amid a flurry of corruption probes.

“Salame abused his position of power, likely in violation of Lebanese law, to enrich himself and his associates by funneling hundreds of millions of dollars through layered shell companies to invest in European real estate,” the U.S. Treasury said in its announcement.

His “corrupt and unlawful actions have contributed to the breakdown of the rule of law in Lebanon,” it added.

Salame’s brother Raja, his son Nady, his former advisor Marianne Hoayek, and former romantic partner Anna Kosakova were also targeted with travel bans and asset freezes.

The new sanctions — which add to measures imposed by three European countries last year — should freeze three apartments in Manhattan, which appear in U.S. property records and a 2021 French judicial investigation file seen by OCCRP and its Lebanese partner, Daraj.

The properties, one of which is previously unreported, were purchased for a combined $5.62 million by subsidiaries of two Jersey-based companies which French investigators said in a 2021 memo were owned by Salame’s brother, Raja.

The U.K. sanctions should freeze commercial and residential properties across the country with a total purchase value of at least 41.56 million British pounds ($59.3 million), according to OCCRP’s analysis of property records. Many of the properties were bought several years ago and their value is likely to have increased significantly.

Properties linked to Salame in the U.K. include a 3.5-million-pound (roughly $4.1 million at the time) London apartment, owned by his son Nady, overlooking Kensington Gardens in one of the world’s most expensive postcodes. The property was first acquired by a Panama shell company, which transferred the property to Riad Salame for free in 2017. Ownership was transferred again to Nady Salame a day later.

The London apartment has been barred from sale since April 2022, according to a restraint order from the country’s Crown Prosecution Service cited in property records. That measure also included five commercial buildings in London, Birmingham, and Bristol owned by Salame’s Luxembourg-based Fulwood Invest S.a.r.l., all of which should be covered by the new sanctions.

Salame’s brother Raja is also the beneficial owner of 10 additional London apartments, including in the affluent Chelsea area, collectively worth at least 8.56 million pounds (almost $13 million), U.K. company and property records show.

“The sanctions are a clear message and warning to corrupt local politicians that they may be able to stifle and suppress the justice system in Lebanon, but cannot control external justice and international accountability,” Nasser Saidi, who served as Salame’s first vice governor and then became Lebanon’s minister of economy and trade and minister of industry, told OCCRP.

Salame, his brother Raja, and his son Nady did not respond to OCCRP’s requests for comment.

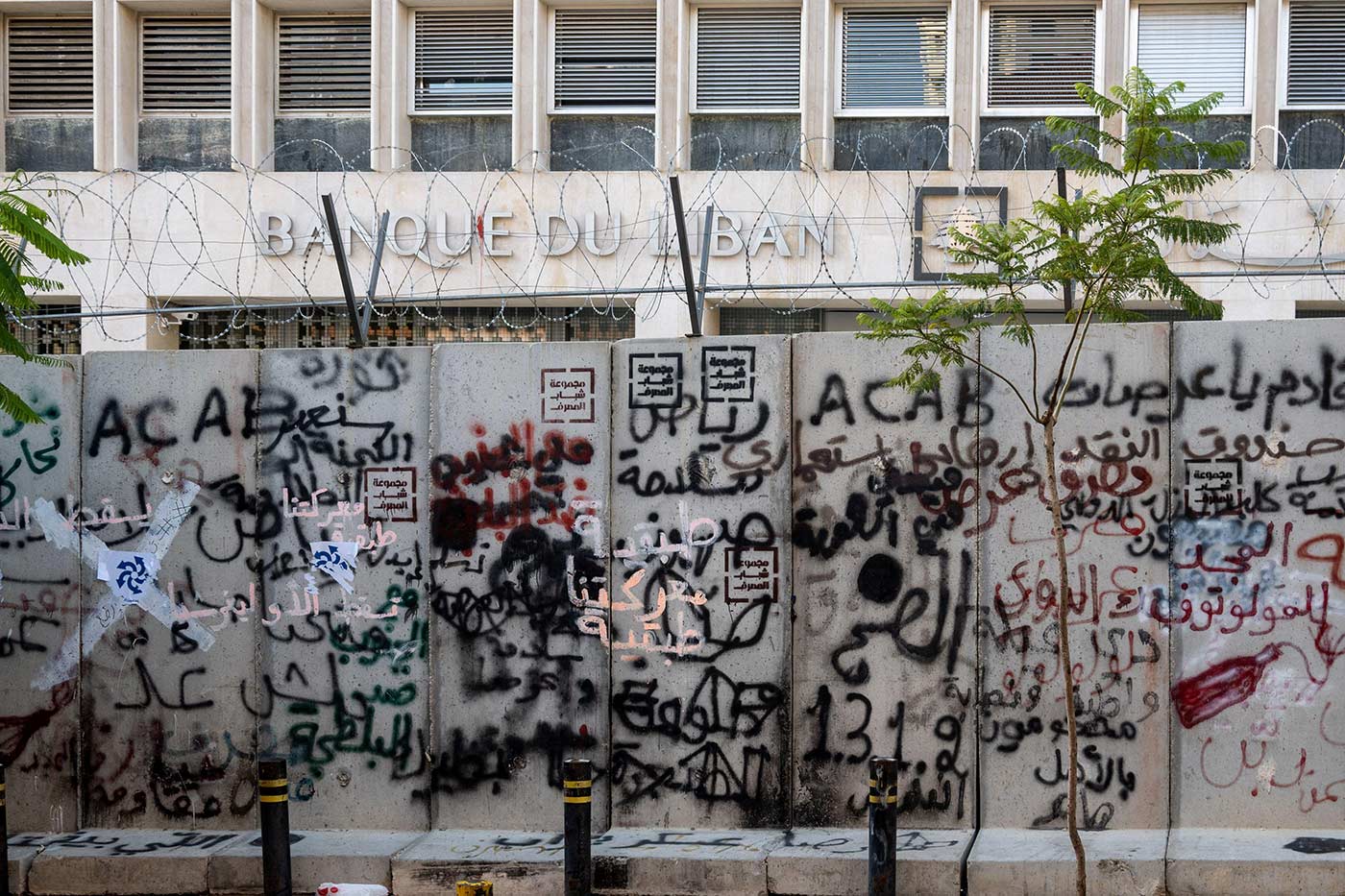

Graffiti and barbed wire around Lebanon’s central bank in Beirut in 2020. (Photo: Abaca Press / Alamy Stock Photo)

Graffiti and barbed wire around Lebanon’s central bank in Beirut in 2020. (Photo: Abaca Press / Alamy Stock Photo)

Previous Asset Freezes

The new sanctions build on the 120 million euros ($130 million) worth of assets linked to Salame frozen last year in Germany, France, and Luxembourg by the European Union Agency for Criminal Justice Cooperation (Eurojust).

Many of the assets were first uncovered in a joint OCCRP-Daraj investigation in 2020 and a second investigation published later that year.

Salame has denied allegations of corruption and told Reuters earlier this month he would challenge the latest sanctions.

But his room for maneuver is limited.

Once lauded for stabilizing Lebanon’s economy after the 1975-1990 civil war, Salame has fallen from grace under accusations of running a country-level "Ponzi scheme” that hastened his country’s historic economic collapse.

Since 2019, Lebanon’s financial meltdown has plunged more than 80 percent of the population into poverty and sent inflation sky-high. Salame and his associates, meanwhile, have been “lining their pockets with money belonging to the Lebanese people,” the U.K. said in its sanctions statement.

Authorities in France, Germany, Liechtenstein, Luxembourg, and Switzerland have since opened criminal investigations into Salame’s alleged embezzlement and laundering of public funds. Several investigators have cited the OCCRP-Daraj investigations.

Salame’s ability to travel is already curtailed by two Interpol “Red Notice” arrest warrants issued by France and Germany earlier this year.

Nor is Lebanon a safe haven. The former bank governor is due to appear before an investigative tribunal there on August 29 for charges pressed against him and his associates in February of embezzlement, money laundering, and tax evasion.

Last week, Salame and his associates’ domestic bank accounts were frozen at the request of the BdL’s Special Investigation Commission. Banking secrecy, which is enshrined in Lebanese law, was also lifted on the accounts of all five after the U.S. sanctions, a Lebanese official who requested anonymity told OCCRP.

French Report Lists Luxury Properties

A file from a French investigation into Salame, seen by OCCRP, shows how the former central bank governor and his associates bought up luxury properties in the country while attempting to conceal their ownership.

It lists multiple properties purchased by them in France between 1999 — six years after Salame became central bank governor — and 2014. These include three floors of an office space on the iconic Champs Elysées worth a combined 8.8 million euros ($9.6 million); two apartments in Paris’s affluent Neuilly-sur-Seine neighborhood; and another two apartments in the 16th arrondissement.

According to investigators, Salame transferred several of these properties, as well as shares in one of his companies, to his children as “donations” in an attempt to “launder the proceeds” of his crimes.

In July, reports emerged that French authorities had transferred millions of euros worth of assets belonging to Salame and his associates to Lebanese authorities.

The file also uncovers how Lebanon’s central bank, despite having no license to work in France, rented office space for 10 years in central Paris that was owned by Anna Kosakova, who is the mother of one of his children.

Kosakova bought the offices using funds transferred from a company in Belize owned by Salame, then leased them to the BdL, according to the report.

Kosakova did not respond to OCCRP’s request for comment.

The Champs Elysées in Paris. (Photo: Brian Jannsen / Alamy Stock Photo)

The Champs Elysées in Paris. (Photo: Brian Jannsen / Alamy Stock Photo)

“Illegitimate” Commission Payments

This month also saw the publication of a leaked audit report which portrayed a central bank where Salame operated with effectively unchecked power.

The preliminary report, prepared for Lebanon’s finance ministry by the New York-headquartered company Alvarez & Marsal, highlighted $107.7 million in “illegitimate” commission payments sent from a BdL account to unknown beneficiaries between 2015 and 2020.

The audit said that the operation “appears to be a continuation” of a scheme that allegedly began in 2002, when Salame approved a contract allowing Forry Associates Limited, a British Virgin Islands company owned by his brother Raja, to receive commissions on the purchase of financial instruments from the BdL by Lebanese retail banks.

Between 2002 and 2015, Forry Associates received payments worth around $330 million from a central bank account, according to a leaked request for mutual legal assistance the Swiss attorney-general’s office sent to Lebanese authorities in 2020.

This month, the U.S. Treasury said Forry Associates “provided no apparent benefit for these transactions” but diverted its earnings to accounts held by Salame and Raja, or to other shell companies. It said that Hoayek “joined [Salame] and Raja in this venture by transferring hundreds of millions of dollars — far more than her official BdL salary accounted for — from her own bank account to those of [Salame] and Raja.”

Hoayek did not respond to a request for comment.

The Alvarez & Marsal report said $107.7 million in commissions were paid between 2015 and 2020 from the same central bank account that had made payments to Forry Associates, though the auditors could not establish where the money ended up because BdL, citing Lebanon's banking secrecy, redacted payment records shared with the international firm.

Between 2015 and 2020, Salame’s personal accounts at the central bank were also credited with $95.9 million in check deposits whose origin Alvarez & Marsal could not establish.

During the same period, Salame transferred $75.1 million to bank accounts in Switzerland, Germany, Luxembourg, the U.K., Lebanon, the U.S., France, and other unknown jurisdictions, the auditors found.

Lebanon’s deputy prime minister, Saadeh Al-Shami, called the report’s findings “shocking” and urged the cabinet to send the findings of the report to Lebanon’s judicial authorities “to be added to the files under investigation”

He also called for granting the auditors permission to cover the period from 2021 to 2023, noting that they were blocked by the bank’s management from accessing certain data and interviewing BdL officials who had information that could be relevant to the audit.

Protesters staging a sit-in outside the central bank in Beirut. (Photo: Paul Doyle / Alamy Stock Photo)

Protesters staging a sit-in outside the central bank in Beirut. (Photo: Paul Doyle / Alamy Stock Photo)

Asset Repatriation

Helen Taylor, Senior Legal Researcher at the U.K.-based charity Spotlight on Corruption, said the coordinated sanctions imposed this month “send a powerful message to Lebanon’s ruling elite that corruption won’t be tolerated and that there needs to be change.”

But she warned that they do not ensure the assets will be repatriated. For that to happen, “law enforcement has to establish that the property is the proceeds of a crime — and that has to go through a court.”

Tom Keatinge, director of the Centre for Financial Crime and Security Studies at the U.K.-based think tank Royal United Services Institute, said that some governments could use legal tools, such as the U.K.’s “Unexplained Wealth Orders,” which would put the onus on Salame to prove that his assets were not acquired with illegally obtained funds.

Such instruments effectively say “‘We think [these are] the proceeds of crime. You need to prove to us that [they] aren’t’,” Keatinge told OCCRP.

Thamer Obeidat, a Jordanian lawyer with experience tracing and repatriating assets in the Middle East, told OCCRP that efforts to repatriate stolen assets will depend on the political will of Lebanese authorities.

He added that recent reforms by Organization for Economic Co-Operation and Development (OECD) countries, including adopting common reporting standards, “will most likely facilitate the efforts of the Lebanese state in locating assets that have been taken by Riad Salame.”

William Bourdon, founder of the French NGO Sherpa that filed a legal complaint against Salame in 2021, said that France’s judicial process to return assets “will take years,” but that “the determination is there.”

He added that it was "disappointing" that the European Council had not yet adopted concrete sanctions.

“There is a lack of political will and courage to do so, while the impact of the widespread corruption on the economic crisis [has] been long recognized,” he said.