The family left in 2012, when protesters started taking to the streets at the beginning of a decade-long civil war. After moving repeatedly, they now live in the Rukn al-Din neighborhood of the capital. Um Ahmed — who asked to be identified by her nickname due to a fear of reprisals from the government — said her family occupies a gloomy rental flat, a far cry from their previous home, which was filled with light from dawn until dusk.

“My house was furnished, the pharmacy was full of medicine, and now I have nothing,” she lamented. “It has all become a dream.”

The ruins of Um Ahmed’s 100-square-meter house in Daraya, a former base for the opposition Free Syrian Army, cost 25,000 Syrian pounds to clear of debris. She was out of money before she could even begin to think of rebuilding.

In May 2014, while watching state television, she learned about the Syrian Reconstruction Committee, an agency set up by the government ostensibly to help people to rebuild their shattered homes. She submitted a claim shortly after, but has heard nothing since.

Like Um Ahmed, thousands of people have applied for compensation from local branches of this national committee, which was set up in 2012. But many report that they still haven’t received help.

An estimated 6.2 million people have been internally displaced by Syria’s long-running civil war, which has plunged the country into a deep economic and humanitarian crisis. Another 5.6 million have fled and are registered as refugees. In 2018, the United Nations estimated the cost of destruction from the war at some $388 billion, nearly 20 times more than Syria’s entire economy was worth last year.

The West has balked at paying for Bashar Al-Assad to rebuild Syria. The European Union and United States have said they will not support the reconstruction of the country until there is a political transition, while the U.S.’s 2019 Caesar Act makes engaging in the regime’s efforts almost impossible.

This week, what has been described as “sham” elections take place in Syria. Criticized for not being free or fair, the election on Wednesday will almost certainly not result in a political transition, as Bashar al-Assad is expected to retain power.

With international funds not forthcoming, the Syrian regime has levied its own tax to finance reconstruction. In 2012, it formed a committee to help rebuild the country under the control of then Deputy Prime Minister and Minister of Local Administration Omar Ghalawanji, who was put on the European Union’s sanctions list the same year.

The committee has raised an estimated 386 billion Syrian pounds, according to an analysis by OCCRP, its Syrian partner SIRAJ, and Finance Uncovered. But there is little evidence that the money has been spent helping civilians like Um Ahmed.

Instead, available records show that the regime’s Reconstruction Committee has mostly allocated funds to government ministries and public institutions, making it impossible to track what is spent. Some of the funds that OCCRP did manage to trace, although they were a small proportion of the whole, went to refurbish military facilities and housing for government forces. Money spent on civilians has often gone to those in pro-government areas.

These findings are consistent with research from the Carnegie Middle East Center, which found President Bashar Al-Assad’s regime has used “selective reconstruction” to shore up its political and economic power in some areas, while ignoring poorer social classes that the regime views as threatening.

For example, in July 2017 the Reconstruction Committee granted 175 million Syrian pounds ($340,000) for maintenance work in Mazzeh 86, a Damascus neighborhood and a backbone of support for the regime.

Meanwhile almost nothing has been rebuilt in nearby Daraya, a former base for the opposition Free Syrian Army, even though it was heavily damaged in the war.

Civilians originally from the rebel-held town of Daraya are evacuated from a rebel-held area of Damascus where they had sought refuge to government-controlled shelters in southern Damascus in September 2016. (Credit: Ammar/Xinhua/Alamy Live News)

Civilians originally from the rebel-held town of Daraya are evacuated from a rebel-held area of Damascus where they had sought refuge to government-controlled shelters in southern Damascus in September 2016. (Credit: Ammar/Xinhua/Alamy Live News)

The Reconstruction Committee “allows for the disbursement of money taken from reconstruction funds, explicitly to the military, police and security services," said architect Mazhar Sharbaji, a governance officer from the Local Administration Councils Unit, an opposition group that monitors reconstruction efforts.

“These concerns are heightened because of a lack of transparency, particularly when it comes to how much money has been collected and where the cash has gone,” Sharbaji said.

"The committee has clearly given money to military security, internal and political security sectors at the expense of civilian victims.”

The Reconstruction Committee did not respond to several requests for comment. A media officer at the Ministry of Finance directed OCCRP to the Ministry of Information to obtain permission to submit questions to the committee. The approval is yet to be granted.

The Promise

In 2013, the government issued Law No. 13, which stipulated that the reconstruction would be funded by a 5 percent levy on direct taxes, such as on the selling of real estate and renewal of car licenses, as well as indirect taxes such as VAT and fees for legal cases. Income taxes were exempt. In 2017, the cash-strapped government doubled the levy to 10 percent.

When the increase was announced, then-Minister of Finance Mamoun Hamdan was quoted in local media explaining that the government needed to collect more funds to rebuild infrastructure and private properties that were destroyed during the war.

Zubair Darwish, then director general of Syria’s General Commission for Taxes and Fees, also told Syrian state newspaper Tishreen that the money would be spent on “supporting restoration and rebuilding what was destroyed, as well as supporting the resettlement of displaced families.”

The public was led to think the taxes were going to rebuild their homes — and, indeed, a system was set up through the Reconstruction Committee to allow citizens to apply for compensation for their destroyed property at a subcommittee in each governorate controlled by the regime of Bashar al-Assad. (Currently the Syrian regime holds 65 to 70 percent of the country, while the rest is controlled by opposition groups or the Kurdish-led Syrian Democratic Forces.) These subcommittees would then send claims to the central Reconstruction Committee for approval.

But a review of documents by OCCRP, SIRAJ, and Finance Uncovered suggests this has not happened.

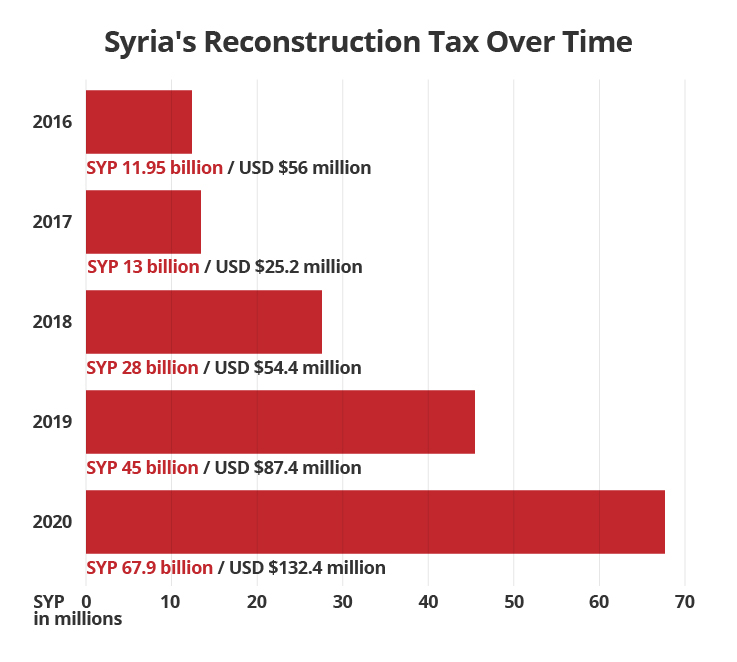

Data from open sources, parliamentary debates, and state media indicates Syria’s government allocated 30 billion Syrian pounds ($266 million) to the Reconstruction Committee in 2013, then 50 billion Syrian pounds (worth $40 million at today’s exchange rate) every year since — a total of 380 billion Syrian pounds, or over $1.4 billion. Earnings from the reconstruction levy have increased over the years from the equivalent of $56 million in 2016 to $132.4 million in 2020.

Syrian Reconstruction Committee Spending disclosures show spending commitments totalling just 263 billion Syrian pounds. This leaves a potential underspend of 117 billion Syrian pounds (approximately $229 million, though the value of the pound has fluctuated wildly during this period). Where the money lies remains a mystery.

The documents suggest only 24.2 billion Syrian pounds ($101 million) — less than 10 percent of the funds allocated to the committee since 2014 — has been spent on rebuilding citizens’ homes.

By contrast, 90.3 percent of the budget has gone to government ministries and public institutions, where it has been impossible to ascertain how the great majority of it has been spent. A small fraction — 1.32 billion Syrian pounds ($2.7 million) — could be pinpointed as having been spent on Syria’s military and security forces.

Money raised by Syria’s reconstruction tax over time. The value of the Syrian pound against the U.S. dollar dropped precipitously during this period. (Credit: Edin Pasovic/OCCRP)

Money raised by Syria’s reconstruction tax over time. The value of the Syrian pound against the U.S. dollar dropped precipitously during this period. (Credit: Edin Pasovic/OCCRP)

OCCRP, Finance Uncovered, and SIRAJ analyzed figures from 16 of Syria’s leading companies — 14 private banks and two telecommunications companies — and found that their contributions rose from 477 million Syrian pounds ($2.2 million) in 2016 to over 1.4 billion Syrian pounds ($2.8 million) in 2019.

"Society’s lack of oversight on the work of government entities allows the regime total freedom to make use of public resources, even humanitarian assistance,” said Haid Haid, a senior consulting research fellow at Chatham House in London.

“Therefore, the regime can use this money to maintain itself and ensure its continuity either by using it for police and security matters, or to finance itself.”

Reconstruction efforts started on the wrong foot, says Syrian architect Mazhar Sharbaji, who has researched how war-torn countries like Lebanon, Germany, Japan, and South Korea managed to rise from the ashes of war. He said an independent commission should have been tasked with overseeing reconstruction, not a government ministry.

"The committee has clearly given money to military security, internal and political security sectors at the expense of civilian victims," said Sharbaji.

It’s a contention that’s difficult to prove, given the lack of transparency. But Sharbaji used the example of his home town, Daraya, which has been devastated by war: About 70 percent of the city is partially demolished, and around half is wrecked beyond repair, Sharbaji said.

To date, electricity is almost non-existent, infrastructure and sewage systems are completely destroyed, and no housing or infrastructure has been built over the past three years, according to Sharbaji.

Funds for the Military

Reports by Syria’s central Reconstruction Committee, which sets disbursement priorities and allocates funds, show that at least 1.27 billion Syrian pounds ($2.6 million) of the cash has gone to the military and police forces.

While the amounts are small, the lack of transparency could mean much more was diverted to the military from a program designed to help civilian homeowners.

Money to the Military

Reporters reviewed successive Committee decisions published on the MOLA website and found multiple examples of spending on properties and medical facilities linked to the army and security forces.

In August 2016, the Reconstruction Committee granted 50 million Syrian pounds (then over $232,000) to 167 members of the army and the police. Later on, the Committee granted compensation to another 60 military personnel.

In July 2017, the committee approved spending 91 million Syrian pounds ($175,000) to reconstruct police and security departments, as well as 100 million Syrian pounds ($193,000) to restore the military hospital in Homs, in western Syria.

The same month it approved spending 480 million Syrian pounds ($930,000) to rehabilitate the road leading to Tishreen Military Hospital in Damascus.

In September 2017, the Committee approved paying for the reconstruction of homes belonging to wounded auxiliary forces who fought with the Syrian army, without outlining how much it would cost.

In November 2017, the committee recommended granting funds for the restoration of 20 apartments owned by the Ministry of Defense for injured military personnel. The announcement did not provide figures.

The Reconstruction Committee recommended the approval of annual work contracts for personnel to care for the wounded from the auxiliary forces as part of the "Wounded of the Homeland" initiative. The Committee did not provide figures.

In 2018, the Committee also allocated 350 million Syrian pounds ($680,000) for the restoration and modernization of military hospitals in the coastal towns of Latakia and Tartus, traditionally pro-regime areas. Another 200 million ($389,000) was spent on restoring the Abdul Wahab Agha Military Hospital in Aleppo.

Osama Kadi, head of the Syrian Economic Task Force, which monitors reconstruction efforts, suggests the reconstruction tax is being used to bail out governmental finances.

“Lack of transparency and widespread corruption within successive Syrian governments for five decades makes it difficult to determine the fate of the huge monies that the regime has obtained from Syrians in the name of reconstruction,” Kadi said.

“Nearly 10 million Syrians still live outside their homes, all the infrastructure continues to suffer from structural problems, as electricity and water are constantly cut, in addition to other services,and basic goods are not well available.”

Gavin Hayman, Executive Director of the Washington-based Open Contracting Partnership, agreed with Kadi’s assessment.

“The huge sums of cash, fragile environment, and lack of oversight make reconstruction funds easy pickings for unscrupulous actors,” he said. “It’s a recipe for disaster. The investments, budget and contracts need to be managed in the open to ensure the cash is used to rebuild the economy and give the country’s citizens the life they deserve.”

For the regime, a large pot of reconstruction cash could be a tempting prospect given the dire state of Syria’s economy. The situation has been compounded by the Syrian pound’s plunge in value. It lost two-thirds of its value against the U.S. dollar in 2020, and hit a record low in March this year. According to the UN’s World Food Programme, prices of basic food soared by 251 percent in the last year alone.

Former rebel-held cities where the Syrian regime has regained control, like Old Homs and the surrounding countryside, Rif-Dimashq, Aleppo, Dara’a, Deir Al-Zour, and many others, remain in rubble. This is despite the fact the government has been collecting taxes in these once-opposition areas.

Haid Haid, from Chatham House in London, said the Syrian government has even refused offers to help citizens in former opposition-held areas, such as Dara'a, suggesting “the regime is not interested in real reconstruction.”

Syrian economic journalist Sameer Tawil said the country needs a national plan, supported by international donors, agencies and companies, to ensure it is rebuilt equitably.

“Syrian citizens and businesses are the victims of a systematic government effort to collect funds through a reconstruction tax, while completely failing to deliver,” he said.

Ali Ibrahim (SIRAJ) contributed reporting.

This story was completed with support from Journalismfund.eu’s Money Trail Project.