Yes, he had said in his TV report that the COVID-19 quarantine camp in the Pakistani city of Chaman, on the border with Afghanistan, lacked proper facilities. The washrooms were in poor condition, he had said; people didn’t have enough water.

But was that such a crime?

The public deserved to know that around 200 camp occupants, some potentially infected with the virus, had broken through a gate and escaped, after protesting against management that had refused to let a sick woman be taken to hospital.

A few days after his report on the camp aired last summer, the Quetta-based reporter for the Urdu-language Samaa News was threatened, abducted, beaten, and jailed.

"My only crime was telling the truth,” Achakzai, 44, told OCCRP.

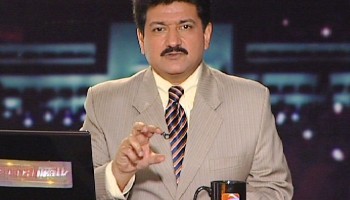

Saeed Ali Achakzai, journalist with Urdu-language channel, Samaa News, reporting from Chaman, Pakistan’s Balochistan province.

Saeed Ali Achakzai, journalist with Urdu-language channel, Samaa News, reporting from Chaman, Pakistan’s Balochistan province.

His case illustrates the dire conditions journalists face in Pakistan, where reporters are routinely harassed, abducted, and sometimes killed.

More than 25 journalists were murdered because of their reporting from 2013 until Imran Khan became prime minister in August 2018, according to Freedom Network, a Pakistani media watchdog. Although police referred many of these killings to prosecutors, just a handful of suspects were ever tried. Just one person was convicted, and even that ruling was overturned on appeal. Since Khan took over, the International Federation of Journalists has recorded the killings of 15 journalists by more or less unknown assailants, seven of them in 2020.

Observers say Khan’s tenure has not improved an existing impunity crisis, with an increase noted in orchestrated harassment campaigns targeting journalists, as well as various methods used to censor media.

“There is a climate of fear and a high level of self-censorship, as many journalists refrain from reporting on ‘red-line’ topics such as the army,” Aliya Iftikhar, research associate at the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ), told OCCRP.

Reporters who criticize the government or expose facts that it wants to hide become targets, she said, adding that in some abduction cases, evidence points to the involvement of government officials. The CPJ has documented the Pakistani security forces’ record of abducting critical journalists for more than a decade.

Pakistan dropped three places — ranking 145 out of 180 nations surveyed — in Reporters Without Borders’ 2020 World Press Freedom Index, which cited a tightening grip on independent media by Pakistan’s military and intelligence agencies.

When asked about press freedom during an official visit to the United States in July, 2019, Khan insisted that Pakistan has one of the freest presses in the world, adding that, “to say there are curbs on the Pakistan press is a joke.”

Heavy censorship, layoffs due to financial constraints and threats that lead to self-censorship have long plagued Pakistan’s media, with local and international experts saying things have deteriorated in recent years.

"I don't mind criticism, but there is blatant propaganda and fake news against the government," Khan tweeted in September, responding to such accusations.

In Balochistan, the southwestern province from which Achakzai was reporting, press freedom has seen serious crackdowns by the Frontier Corps, an 80,000-troop military security unit tasked with surveilling the country’s borders with Afghanistan and Iran.

Nobody at Achakzai’s office took the telephone threats he received from the commander of the Frontier Corps seriously. When he and a colleague were summoned to the commander’s office a few days later, he thought a conversation would solve any problems that arose.

But when the two entered a building, officers took their phones, ordered them to unlock the devices, and asked them whether they supported the Pashtun Tahafuz Movement, a group that advocates for the human rights of ethnic Pashtuns, the largest minority in Pakistan.

Though the reporters insisted they had nothing to do with the movement, they say the officers quickly tied their hands, blindfolded them, and handed them over to another unit. And that, Achakzai said, is when he was kicked and beaten with batons and cables.

Saeed Ali Achakzai, reporter for Urdu-language channel, Samaa News, shows bruises from beating by law enforcement officers. Courtesy of Saeed Ali Achakzai.

Saeed Ali Achakzai, reporter for Urdu-language channel, Samaa News, shows bruises from beating by law enforcement officers. Courtesy of Saeed Ali Achakzai.

“At one point I thought I would be killed, and that my killers would go free,” he said.

When news of the detention of the two reporters spread, the journalism community held demonstrations outside the building, leading to their release 48 hours later. But despite being freed, Achakzai said he has been placed on a “suspected person watch list” that bans him from leaving his city, and requires him to inform police before he leaves his house.

Achakzai’s story is far from an isolated incident, explained Shah Nawaz Tarakzai, 41, who works with Radio Mashaal, a Pashto-language broadcaster that is a member of Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty.

Tarkazai said he was abducted in 2017 by government officials who blindfolded him and drove him to an unknown location, where for two days they interrogated him about his work. His family is still emotionally traumatized by the incident. “They were looking for me in hospitals and morgues,” he said of his relatives’ frantic search.

Although his ordeal occurred a year before Khan came into power, he said that “freedom of media has declined in the country during Prime Minister Imran Khan’s regime.”

Journalists who report on the culture of violence, corruption, crime and the disappearances of their colleagues, “are almost always harassed, intimidated, or even killed by state and non-state actors,” he said.

The forced disappearances, he said, “are used as a weapon to silence media professionals by making sure that journalists are performing their duties under constant fear.”

A previous version of the story included comments from a source that were collected by the reporter originally for use by another news organization. OCCRP has removed the information. We regret the error.