After Bulgaria’s state-owned aviation firm traded a Soviet-era military transport helicopter for a more modern Russian model better suited for shuttling officials around the country, the company’s director boasted that the government “did not pay a penny for it.”

Government officials had hyped the bargain in Bulgarian media when the deal was made in 2012, and Pencho Penchev, then head of the state company Aviootryad 28, told a local aviation publication that his firm had delivered.

“We received the Russian machine on the principle of exchange,” he was quoted as saying in the August 2012 issue of AeroPress magazine.

But the government was not the only beneficiary of the deal, according to leaked documents, including bank records and contracts, from a London-based company services firm called Formations House.

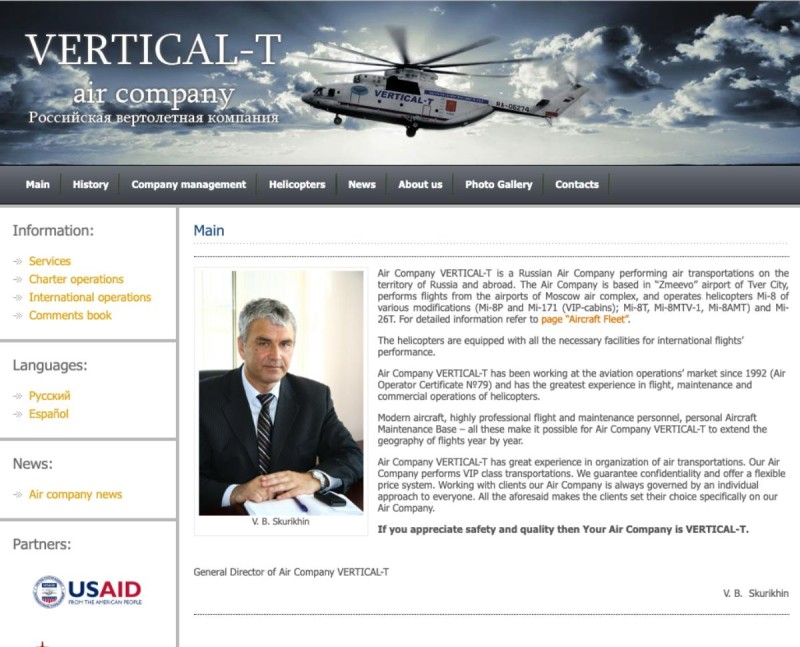

Vladimir Skurikhin, a Russian aviation tycoon, appears to have pocketed almost $1.3 million by using two companies to facilitate the chopper swap, according to the documents. However, it is difficult to determine whether the paperwork matches the reality of the deal or obscures it, and Skurikhin did not reply to multiple requests for comment.

Whatever happened, experts say, Formations House should have noted glaring irregularities in transactions by a company it had created for Skurikhin, STS Corporation LLP, which was at the center of the deal. Formations House managed accounts for STS, and had access to the contracts and transactions involved in the swap.

Details of the deal and several others found in STS records kept by Formations House should have prompted “reasonable suspicion on the part of the accountant that money laundering was in train,” said Ray Blake, an anti-financial crime consultant.

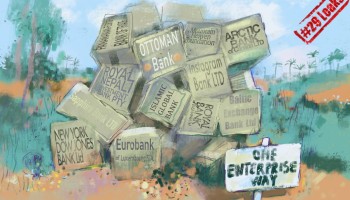

They add to a body of evidence showing a pattern of obliviousness on the part of Formations House to its clients’ activities. The firm created tens of thousands of companies for people around the world, some of which have been used in multi-million-dollar fraud scams. Some of those schemes have now been uncovered by reporters sifting through the trove of internal documents from Formations House, which were obtained by the information activist group Distributed Denial of Secrets.

The leaked data also exposes the lax regulatory environment in the UK, which experts say allows company registrars like Formations House to ignore the suspicious activities of their clients with few repercussions. The firm was able to carry out questionable deals even as its founder, Nadeem Khan, was being investigated for money laundering in the UK. He was charged in April 2014, but died before facing trial.

In an emailed statement to journalists, Formations House’s current owner and Khan’s stepdaughter, Charlotte Pawar, said the leaked data has been reported as stolen, and that the firm has faced extortion attempts. She did not provide evidence to support these claims, despite several inquiries from reporters.

Dirty Laundry

In addition to creating the company, Formations House provided it with services including accounting. Among the leaked documents are records of several STS transactions unrelated to the helicopter deal, but which experts say should have been warning signs for anyone carrying out proper due diligence.

In 2014, STS transferred more than $300,000 to a Scottish LP, Progate Solutions. That company was part of a scheme that funneled billions of dollars of embezzled tax revenue out of Russia. The scandal became known as the Magnitsky case after Sergei Magnitsky, the lawyer who uncovered the fraud and then died after mistreatment in a Russian prison in 2009.

“They should have been doing ongoing due diligence, which can be as simple as a Google search,” said Ben Cowdock, lead investigator at the UK chapter of Transparency International.

“Currently, egregious behavior appears to go unpunished, proving little incentive for rogue agents to stay within the law.”

The leaked documents show Formations House continued taking on questionable clients after the UK’s tax authority warned in 2016 it could face criminal prosecution if it did not put proper due diligence checks in place. HMRC’s agents visited its offices four months after the firm’s exploits were revealed in a long profile by the UK’s Guardian newspaper.

In a citation letter, HMRC warned Pawar that Formations House needed to “identify and scrutinise complex or unusually large transactions [and] unusual patterns of transactions” — both of which would have applied to STS activities, according to experts. Yet there is no evidence the regulator took any further action.

Such checks are not regular enough, according to David Clarke, chair of the advocacy group Fraud Advisory Panel, and former director of the National Fraud Intelligence Bureau, meaning that formation agents have little reason to follow the rules. “Because people are not inspected, there is a more of an incentive to do the wrong thing than to do the right thing,” he said.

In response to a series of articles by OCCRP and its partners exposing the inner workings of Formations House — known collectively as the #29Leaks project after Formations House’s London address at 29 Harley Street — the UK’s anti-corruption chief, John Penrose, said the country must introduce more stringent rules for creating new companies.

“Reputations take years to earn but can be lost in an instant, so we simply can’t let kleptocrats or crime lords channel dirty money through Britain’s system,” he told The Times of London, which worked on the project.

Pawar said that STS is no longer a client of Formations House and that the firm has improved its compliance processes since 2016. HMRC declined to comment on the outcome of its investigation into Formations House or any follow-up actions it may have taken, saying it was unable to discuss issues related to any specific business.

How the Deal Went Down

Rather than the cheap and simple exchange described by Bulgarian officials, reporting by OCCRP and its Bulgarian member center, Bivol, shows the 2012 helicopter deal was a complicated and costly scheme, involving closely connected companies and a curious cast of characters.

On its face, the trade looked like a good one — but only if the price tags authorities put on both helicopters are to be trusted.

An April 2012 contract shows that STS paid Vertical-T $847,000 to buy the Mi-8, which it would trade to the government for the older Mi-17. A June 2012 exchange contract states that the value of the Mi-17, which the government was giving up, was about $900,000.

The similar values of both machines — at least as stated in those contracts — would appear to be the basis of Penchev’s claim that the government did not “pay a penny” for its new VIP helicopter, although it would still represent about a $53,000 loss.

Yet the subsequent sales contract between STS and Inoxis suggests that Aviootryad’s appraiser undervalued the Mi-17 by more than $1 million. That contract shows STS sold the Mi-17 to Inoxis for $2.1 million. Since STS had given the government a machine valued at $847,000, it seems to have netted a profit of around $1.3 million on the deal, at the expense of Bulgarian taxpayers.

Bulgarian defense ministry records also indicate that the Mi-17 was worth much more than assessors said. According to those public documents, the ministry sold five aging Mi-17 helicopters just the year before for about $2.5 million each, and one for $2.7 million.

Furthermore, Rumen Nikolov, the head of Inoxis, told OCCRP that after purchasing the Mi-17 from STS for $2.1 million, he sold it to another party for even more money, though he declined to name the price or identify the buyer.

“Yes, we made a profit and paid all taxes due,” said Nikolov, without elaborating. The Mi-17 is now registered in Moldova.

Ilian Vassilev, a former chairman of the auditing firm Deloitte Bulgaria who has also served as Bulgaria’s ambassador to Russia, said the opaque nature of the transaction should have served as a red flag.

“Swaps of this nature are typical for state-owned enterprise managers that want to pocket the difference in price differentials, which can naturally emerge from lack of independent market valuations,” he said.

“That is why it is essential that such transactions take place in the open, via a tender process.” .

Since the assessed value of the Mi-17 is inconsistent with what it actually sold for, assessors could have undervalued the Mi-8 as well. One reason for that would be to avoid paying taxes on the sale. If that was the case, Formations House had a responsibility to look into the deal and determine whether tax evasion might have been occuring, according to Blake, the financial compliance expert.

“At the very least you would expect the accountant to have made enquiries to establish any additional facts or context that could assuage the suspicion,” he said.

Meanwhile, the leaked Formations House documents raise serious questions about who orchestrated the big chopper swap, which was presented to the public as a bargain for Bulgarian taxpayers.

After receiving the newer helicopter, Aviootryad’s director at the time, Penchev, told AeroPress magazine that two firms, which he did not name, had come forward when the tender was issued.

“We decided on the proposal of a Russian company that had a nice Mi-8,” he told the magazine.

In fact, the “Russian company” did not bid directly, according to procurement documents. Instead, the bid was made by Skurikhin’s STS, which at the time was owned by two Seychelles-based companies.

On paper, STS was owned by one Evaline Joubert. She signed an April 11, 2012, contract to buy the Mi-8 from Vertical-T, which was represented by Skurikhin, the Russian aviation tycoon. As it turns out, Skurikhin was also the beneficial owner of STS.

Joubert signed a second contract that day, cementing the STS sale of the old Mi-17 to Inoxis, the Bulgarian company that promised to pay $2.1 million for it. Then on June 26, 2012, STS signed a contract with Aviootryad, the state company, sealing the swap.

But that wasn’t the whole scheme. Records show STS signed another contract that June, in the Estonian capital of Tallinn, with Belize-registered Powerstone Holding LTD.

After payments from Inoxis for the old helicopter landed in its Cypriot bank account, STS made four transfers totalling $1.25 million — almost the same sum it earned from the swap — to Powerstone’s account at ABLV, a bank in Latvia.

Six years later, ABLV would collapse after the United States cut it off from its financial system for laundering money and working with unsavory clients.

The Players

It is difficult to determine who is behind Powerstone because of the lack of corporate transparency in Belize. The company, which on paper shared a suite in Belize City with almost 100 other firms, is now listed as inactive.

In response to a reporter’s inquiry, an Aviootryad spokesperson insisted that the helicopter swap had been “economically advantageous for the state.”

Rumyana Yankova-Ivanova, the company’s legal adviser, said in an email that the Mi-17 had been in poor condition and that its value of nearly $900,000 had been properly established by an independent appraiser. She did not explain why — if that assessment was correct — the Mi-17 was then sold to Inoxis for $2.1 million.

The leaked documents, as well as company registries in Russia and the UK, show that Skurikhin owned both companies involved in the helicopter swap.

The STS contract listed Joubert as the company director — a role she played in a number of entities registered in offshore jurisdictions, including the Seychelles and British Virgin Islands. She was also a proxy at STS for Skurikhin, who was the sole owner of Vertical-T.

Although on paper STS was owned in 2012 by two companies registered in the Seychelles, the phone contact listed in Bulgaria’s public procurement registry was the same as the number listed for Skurikhin’s Vertical-T. The Seychelles companies also signed a contract for STS to represent Vertical-T outside the Russian Federation, the leaked documents show.

In 2016, when updated UK transparency laws required companies to declare individuals with significant control, Skurikhin was registered as the beneficial owner of STS, indicating that he had at least a 75 percent stake in the company.

Vertical-T and STS did not respond to multiple requests for comment.

Inoxis, the Bulgarian company owned by Nikolov that generously took the aged Mi-17 off STS’s hands for $2.1 million, regularly receives government contracts.

On his LinkedIn profile page, Nikolov lists a long history of positions within the Bulgarian military establishment, including a stint at the defense ministry’s procurement department. Nikolov’s military and defense experience appears to have served him well. Between 2010 and 2015, Inoxis won more than $3 million worth of public procurement contracts.

One of those contracts, in 2015, paid Inoxis $526,560 to replace the engine of a VIP Mi-8 helicopter – the same one the Bulgarian government had swapped for the old Mi-17.