A cargo airline owned by a company with past ties to Azerbaijan’s ruling Aliyev family won some lucrative contracts from the U.S. military, according to documents obtained in 2016 through Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) requests filed in the U.S. by a reporter for the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project (OCCRP).

In late 2005, as the war in Afghanistan was in its fourth year, the U.S. government began contracting with the carrier, Silk Way Airlines, to transport ammunition and other non-lethal materials to U.S.-trained Afghan forces and the International Security Assistance Force (ISAF) in the country.

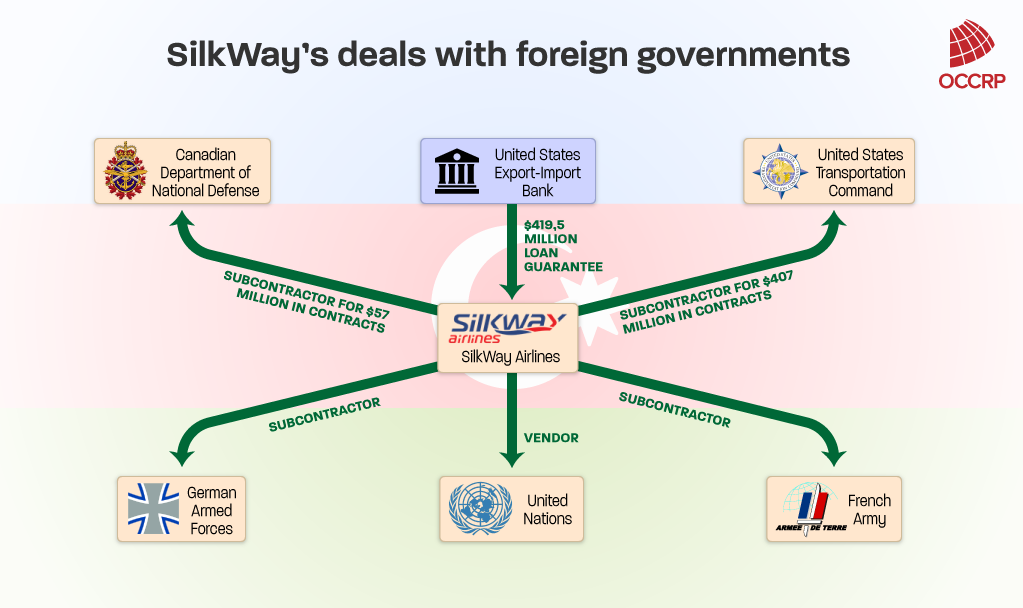

Silk Way participated in contracts worth more than $400 million with the U.S. Defense Department’s Transportation Command for more than a decade, thanks in part to a $420-million loan guarantee from the U.S. Export-Import Bank to enable it to buy three 747-8 freighter airplanes from Boeing.

The airline has had its share of controversy. Last July, the Bulgarian website Trud posted leaked correspondence between Azerbaijan and Bulgaria showing that Silk Way had used at least 350 flights with diplomatic clearance to surreptitiously transport “hundreds of tons of weapons” to war zones in the Middle East and elsewhere between 2014 and 2017.

Nevertheless, Boeing appears unfazed, and Silk Way’s business with the U.S. aviation giant continued to grow, with the Azerbaijanis signing a $1 billion deal with the company in April 2017 for 10 new 737 MAX passenger planes. This newer deal does not involve any U.S. guarantees, and it is unclear how it is being financed.

Last October, airline officials announced that Silk Way planned to buy two more 747-8 Freighter airplanes. Again, no financing details were provided. Silk Way officials did not respond to reporters’ requests for comment; nor did the Boeing Corporation want to shed light on the matter. “We don't discuss the contractual terms of any of our customers,” said Boeing spokeswoman Elena Alexandrova.

Neither the loan guarantee nor the full extent of the Pentagon’s relationship with Silk Way Airlines, which goes back to 2005 and continues today, have been previously reported.

Silk Way’s fleet is growing, and while these revelations may raise a few eyebrows, it seems that the sky truly is the limit.

Skeletons in the Closet

The airline is owned by Silk Way Group, which, at least at one point, was closely associated with Azerbaijan’s ruling Aliyev family (which has used its planes for private trips) and has benefited from benevolent state deals. Information obtained through FOIA requests shows that Silk Way Airlines took steps to conceal its owners’ identity, perhaps to improve its chances of winning the valuable U.S. loan guarantees and military contracts.

A possible reason for that reticence is Azerbaijan’s poor record on corruption and human rights. The country ranks 122nd out of 180 countries in Transparency International’s corruption perception index, while President Ilham Aliyev's family owns luxury properties around the world worth over $140 million. The Panama Papers and other leaks have implicated the country’s first family as being involved in nearly all sectors of the Azerbaijani economy, from luxury hotels to mining to banking.

“Silk Way was a crucial partner for the Azerbaijan-Central Asia route, which was used to bring in one-third of all non-lethal materiel [into Afghanistan],” explains Matthew Bryza, the U.S. ambassador to Azerbaijan from 2010-2011. “The U.S. military rightfully focused on its urgent operational-logistical needs rather than on democracy.” The former ambassador added that democracy promotion remains a vital U.S. interest, but must be balanced against other considerations.

Human rights activists who have followed Azerbaijan over the years, however, believe the decision to use Silk Way Airlines was short-sighted.

“The dilemma [between democracy promotion and urgent military needs] is quite often put that way, but U.S. foreign policy traditionally has longer-term goals. Among those are promoting rule of law, a diverse economy, more accountable governance, [and] democratization,” said Nate Schenkkan, project director of the Nations in Transit report at Freedom House, a US-based nonprofit that monitors democracy and human rights around the world.

Azerbaijan's President Ilham Aliyev casts his vote during presidential elections, Baku, April 2018. Credit: Vugar Amrullayev / Azertac / Reuters

Azerbaijan's President Ilham Aliyev casts his vote during presidential elections, Baku, April 2018. Credit: Vugar Amrullayev / Azertac / Reuters

A Deal as Smooth as Silk

Washington paid handsomely. In 2014, through the Export-Import Bank of the United States (EXIM), the U.S. government awarded a $419.5 million loan guarantee to Silk Way Airlines to buy the three Boeing 747-8 Freighter airplanes.

The deal was as controversial as it was generous. According to the loan guarantee agreement, if the privately-owned airline failed to repay the loan, the loss would be borne not by its shareholders, but primarily by the state-owned International Bank of Azerbaijan.

This was followed by an additional $1 billion contract with Silk Way for 10 more passenger planes in April 2017, and plans to buy two more 747-8 Freighter airplanes in October that same year. EXIM was not involved in that deal, as the bank has sharply curtailed its lending under increasing pressure from politicians who want to shut it down.

The U.S. government’s 2014 loan guarantee allowed Silk Way Airlines to borrow money at a reduced interest rate, as there was no risk to the lender of a default on a loan backed by the U.S. government. According to the minutes of an EXIM board meeting, the loan guarantee was awarded on the grounds that the transaction with Boeing would support approximately 2,800 American jobs at Boeing, GE, and Gulfstream.

However, the guarantee also meant that, if the Azerbaijani state bank itself failed to replay the airline’s loan, U.S. taxpayers would be on the hook. The guarantee allowed Silk Way Airlines to borrow money at an interest rate of three-month LIBOR + 0.6 percent (LIBOR is a benchmark interest rate that banks charge for lending money to one another).

This is nearly the same rate given six months later to General Electric Capital, a U.S. company with a much higher credit rating, which received a non-EXIM backed loan with an interest rate of one-month LIBOR + 0.5 percent. In other words, the loan guarantee enabled Silk Way Airlines to get U.S. government-backed financing at nearly the same rate as General Electric Capital.

EXIM and its Critics

EXIM, or the United States Export-Import Bank, is the U.S. government’s official export credit agency. Founded in 1934, its goal is not to compete with commercial lenders, but instead provides capital for transactions and investments which other lenders would be unwilling to undertake, given financial or political risks.

Opinion remains divided about its efficacy, if not its purpose.

“For years, [the bank] has been a political punching bag for conservatives who have called it a tool of corporate cronyism and a meddler in free markets,” New York Times reporter Alan Rappeport wrote in May 2017.

EXIM has also come under fire after a series of investigations found it gave guarantees to suppliers of mining companies accused of slave labor, to Mexico’s state-owned oil company Pemex with its history of workplace casualties and explosions, and to a whole host of environmentally disastrous projects.

“Export-Import Bank has never been too concerned about who they are giving loan guarantees to, so long as the loan gets paid,” said David Kramer, who served from 2008-2009 as the U.S. Assistant Secretary of State for Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor.

“I remember one incident when I was at the State Department where I told them a certain company shouldn’t receive a loan guarantee as it was owned by a person who had blood on his hands. Their question was, how much blood?”

To assuage concerns over repayment, EXIM officials received a guarantee from the state-owned International Bank of Azerbaijan that it would repay the loan in case Silk Way was unable to do so.

“Staff believe the financial condition of Silk Way is not yet sufficiently strong enough to justify a financing of this size, and therefore the International Bank of Azerbaijan will also guarantee the transaction, and as the strongest of the guarantors, IBA will be the primary source of repayment,” stated the minutes of a meeting of EXIM’s board directors in June 2014.

These revelations have caused consternation amongst anti-corruption activists, who worry that Azerbaijani taxpayers could end up bailing out a private company with ownership ties to the rulers of their country — with the assistance of a U.S. government body. (The bank has also been implicated in the Azerbaijani Laundromat, a massive scheme that pumped nearly $3 billion out of the country through various shell companies.)

As Freedom House’s Schenkkan puts it, “[This is] not the kind of thing that the United States has traditionally wanted to see in how they work with partner countries and allies… So this is something that even if it’s not EXIMs role to look into, someone should take a look at this and see if this is what we want to endorse.”

“In Azerbaijan, where one family dominates economically and politically, and is then using state institutions to back its economic projects, there’s an obvious conflict of interest,” he continued.

Notably, just a few months before the 2014 EXIM transaction, the Azerbaijani government made an “unprecedented” announcement that there would be a $500 million infusion into the International Bank of Azerbaijan, a point that was favorably noted by the EXIM board before approving the transaction.

The International Bank of Azerbaijan was not such a secure guarantor after all.

Two currency devaluations in 2015, combined with crashing oil prices, adversely affected the bank, causing it to default on $3.3 billion in liabilities and file for protection under Chapter 15 of the U.S. Bankruptcy Code in New York. This prompted the Azerbaijani government to step in and take over $2.2 billion in external debt owned by the bank in March 2018.

In addition to its relationship with the U.S. government, Silk Way Airlines has also worked as a subcontractor for the Canadian Department of National Defense, the German armed forces, and the French army. The American government was unable to say exactly how much of the $400 million has gone to Silk Way Airlines, as contracts are awarded to prime contractors and not subcontractors.

SilkWay Airlines’ contracting deals with foreign governments. Click to enlarge. Credit: Edin Pasovic / OCCRP

SilkWay Airlines’ contracting deals with foreign governments. Click to enlarge. Credit: Edin Pasovic / OCCRP

Strictly First Class

Silk Way’s ties to Azerbaijan’s ruling family have long been reported.

A 2010 investigation by Radio Free Europe found that Arzu Aliyeva, the president’s younger daughter, was one of three owners of Silk Way Bank, the financial arm of Silk Way Holding. After this information was revealed, the president’s spokesperson defended her right to be an independent businesswoman.

According to a 2017 Silk Way Bank annual report, neither the Aliyev family nor Silk Way Group appears to still hold any stake in the bank.

Silk Way Holding, also referred to as Silk Way Group (SW Group) on its website, is a conglomerate that has currently listed 11 companies in its portfolio, including the airline. Until June 2017, it had listed 14 different companies, including Silk Way Bank (whose entry was removed from their website over the course of reporting this investigation).

Over the years, the Silk Way group of companies — which includes Silk Way Airlines, Silk Way Construction, and Silk Way Insurance, among others — have taken over large parts of Azerbaijan’s aviation sector. So influential was the airline that in 2014, a U.S.-based competitor, Kalitta Air, opposed a request by Silk Way West Airlines to the U.S. Department of Transportation for a foreign air carrier permit on the grounds that “Azerbaijan is not an open and competitive market for U.S. carriers — unless, of course, they contract with Silk Way.”

Kalitta’s objection stated that “Silk Way has set itself up as the gatekeeper of all air transportation (at least in the cargo sphere) in and out of Azerbaijan” by managing to “own and control not only the Baku Airport Cargo Terminal, but also the airport’s ground handling, catering, maintenance and repair, duty free shop, business aviation and helicopter service, not to mention the Sheraton Baku, an insurance company and other concerns.”

Silk Way Holding’s domination of the country’s aviation sector owes a lot to the 2003 privatization of state carrier AZAL airlines by Azerbaijan’s Ministry of Economic Development. This process, by which Silk Way absorbed many of the former state airline’s businesses, was described by a financial expert as “dodgy from the start” because it took place in secret, without benefit of bids and tenders.

The Aliyevs have their fingers in plenty of other pies. A similar privatization of the telecom sector ended up with the family earning about $1 billion in bribes in cash and share value, according to an earlier OCCRP story. The investigation also found that the money was funneled to the first family through various secret offshore companies. These companies have enabled the Aliyevs to control stakes in gold mines, telecommunications and construction businesses in Azerbaijan.

True to form, Silk Way Holding also has an offshore company that operates in the shadows and plays a pivotal role in its functioning: the International Handling Company (IHC).

A Silk Road to the Caribbean

The earliest known reference to Silk Way Airlines’ ownership comes from a document called the “AMC Form 207” that Silk Way filed in 2006, a copy of which was obtained through a FOIA request. Any airline wishing to move cargo for the U.S. military must submit this form.

In its application, Silk Way Airlines stated it was owned by IHC, an offshore company based in the British Virgin Islands (BVI). It did not provide any information on who owned IHC, despite being explicitly asked to do so on the form. The IHC owner could not be independently identified due to secrecy laws in the BVI.

The U.S. Transportation Command did not respond to reporters’ questions as to why Silk Way Airlines was allowed to move cargo for the military despite not revealing its ultimate ownership; a standard requirement in such cases.

In 2007, in a separate application filed before the Department of Transportation in Washington, Silk Way Airlines stated that 40 percent of the company was owned by IHC, while 60 percent was now owned by SW Holding, “effectively controlled” by Zaur Akhundov, an Azerbaijani citizen. Once again, the airline did not disclose IHC’s owners in the documents it filed.

IHC is linked to the Aliyev family through its director Jaouad Dbila, who in 2016 was also on the supervisory board of Silk Way Bank. Furthermore, Dbila has reportedly served as a proxy for the first family’s business interests in the past.

As director of Silk Way Inn from early 2012 to late 2013, Dbila developed a track record of managing investments for the Aliyevs and their business associates in neighbouring Georgia, according to an investigation by independent news site Meydan TV. In 2014, Dbila won an award from Ilham Aliyev, Azerbaijan’s president, for “services in civil aviation.”

By 2015, Dbila was director of the new Terminal One at Baku International Airport, according to an industry publication by SITA, an information technology company in the air transport industry. Jaouad Dbila could not be reached for comment, despite several emails to Silk Way Airlines and his brother Mike Dbila, who serves as the airline’s representative in Chicago.

A SilkWay Airlines Boeing in Milan Malpensa Airport, 2016. Credit: Anna Zvereva / Wikimedia Commons

A SilkWay Airlines Boeing in Milan Malpensa Airport, 2016. Credit: Anna Zvereva / Wikimedia Commons

No Easy Loan

The plan to apply for what would later become the $420 million loan guarantee was first raised by the general manager of Azerbaijan Airlines during a 2008 visit of the U.S. Export-Import Bank chairman to Azerbaijan, according to a U.S. diplomatic cable released by Wikileaks.

For reasons not altogether clear, a loan application was only received in early 2014, six years later. By that time, IHC was no longer in the picture — at least, not in the official loan paperwork, which requires the submission of ownership and shareholder information.

Sometime between 2007 and 2014, IHC gave up its stake in Silk Way. But while the IHC relinquished its ownership stake (at least on paper) it did not relinquish control over the airline.

In 2011, a Russian-born manager, Grigory Yurkov, was given power of attorney for both Silk Way Holding and IHC, according to Luxembourg’s official gazette. The power of attorney ensures that, through Yurkov, IHC would be able to enter agreements and make financial commitments on behalf of Silk Way Airlines, regardless of the airline’s formal ownership.

“While it is generally not illegal to have such a structure, such an ownership structure can be used to conceal and/or evade disclosure obligations and shroud conflict of interest or the identity of persons involved,” said Tom Gorman, a partner at the law firm Dorsey & Whitney LLP who reviewed the history of the company’s ownership.

“Such a concealed conflict of interest could have significant political implications,” he continued, pointing to the earlier 2010 investigation in which the president’s daughter Arzu was found to be a partial owner of Silk Way Bank, one of the companies in the Silk Way conglomerate.

Filings by Silk Way Airlines in 2015 before the Department of Transportation in Washington also show that IHC owns five of 11 aircraft used by Silk Way Airlines. One expert sees this as a possible mechanism for funneling money towards the owners of IHC, by having Silk Way pay an inflated amount for renting these aircraft.

Due to the formal change in ownership, EXIM did not ask any questions about IHC or its role before approving the loan guarantee, despite the offshore company’s continued influence over the airline.

When questioned on this point, a spokesperson of EXIM redirected reporters to minutes of an EXIM board meeting containing no discussion of IHC.

Meet the Mystery Man

Many unanswered questions remain about Silk Way and its business dealings. However, the company’s 2014 loan guarantee application did reveal one important fact: by that time, Zaur Akhundov, a former Azerbaijani government official, had become the 100 percent owner of the entire Silk Way Group. By that time, the firm and its many holdings were already worth billions of dollars.

Little is known about Akhundov, who has managed to maintain a relatively low profile. Observers who have been following corruption scandals in Azerbaijan, however, say they recognize a familiar pattern.

“This is a recurring aspect of corrupt business transactions in Azerbaijan. Someone will come out of nowhere and become the face of a company, although they won’t be the final beneficial owners,” noted Richard Kauzlarich, the U.S. ambassador to Azerbaijan from 1994-1997.

“I don’t personally know [Akhundov], but it sounds like a familiar pattern. This business model has been a feature of Azerbaijani transactions over the years,” he continued, pointing to an earlier Global Witness investigation into Azerbaijan’s oil company.

In 2010, Akhundov was listed as the chair of Silk Way Bank’s supervision board. The same document also listed the president’s daughter as a founder-shareholder in the bank.

The application filed by Silk Way Airlines with EXIM also reveals previously unreported personal information on Akhundov, who could not be reached for comment despite several emails and phone calls to his lawyers in Washington.

Akhundov, who is now 50, has spent most of his life working for the Azerbaijani government in various capacities. He started his career in the planning committee of the Azerbaijan government around 1991, and later moved to the Ministry of Foreign Economic Relations. He obtained a PhD in economics from the Azerbaijan State Economic Institute in 1997, after which he was appointed for three years as director of Cargo Aviation company of state-owned Azerbaijan Airlines.

Akhundov was director of Baku’s Airport during the 2003 privatization wave, during which many of Azerbaijan Airlines’ businesses were absorbed by Silk Way Holding. He was a founder of Silk Way Airlines in 2001 and later appointed its president in 2005; he was subsequently elevated to president of Silk Way Holding in 2006, a position he has held ever since.

Based on his background of government service, it is unclear how Akhundov became the owner of a billion-dollar conglomerate with more than 10 aircraft, an insurance company, a construction company and an aircraft maintenance company, to name a few of the enterprises in the Silk Way Group.

It is also not clear how he came to acquire ownership of the group from IHC, or why IHC continues to have the power to enter into agreements and make commitments on behalf of Silk Way Airlines.

“Azerbaijan can be described as a centralized, vertical pyramid where the benefits go to one family that collects rents throughout the economy,” said Schenkkan of Freedom House.

“This includes all sorts of transactions, not only official state transactions that might involve taxes and public funds, but also things that involve what we normally consider the private sector: import-export, consumer goods, transport - any area of the economy, the family has a stake in it and receives a cut on what takes place.”

This story was produced in collaboration with the Stabile Center for Investigative Journalism, Columbia University.