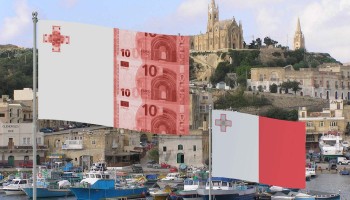

Next month, the European Union is due to review this blacklist. And as it does so, it may want to take note of a prominent individual who, thus far, has slipped through the cracks.

A joint investigation by the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project (OCCRP), the Russian newspaper Novaya Gazeta, and the French Le Monde reveals the extent to which one of Russia’s most infamous oligarchs — Putin’s childhood friend Boris Rotenberg — is entrenched in the French Riviera.

Arkady Rotenberg, Boris’s even wealthier older brother, was one of those sanctioned by the EU in 2014, losing his extensive Italian properties and the right to travel to Europe. But — supposedly thanks to the Finnish citizenship he obtained through an earlier marriage — Boris himself was left off the list, enabling him to continue enjoying his French assets.

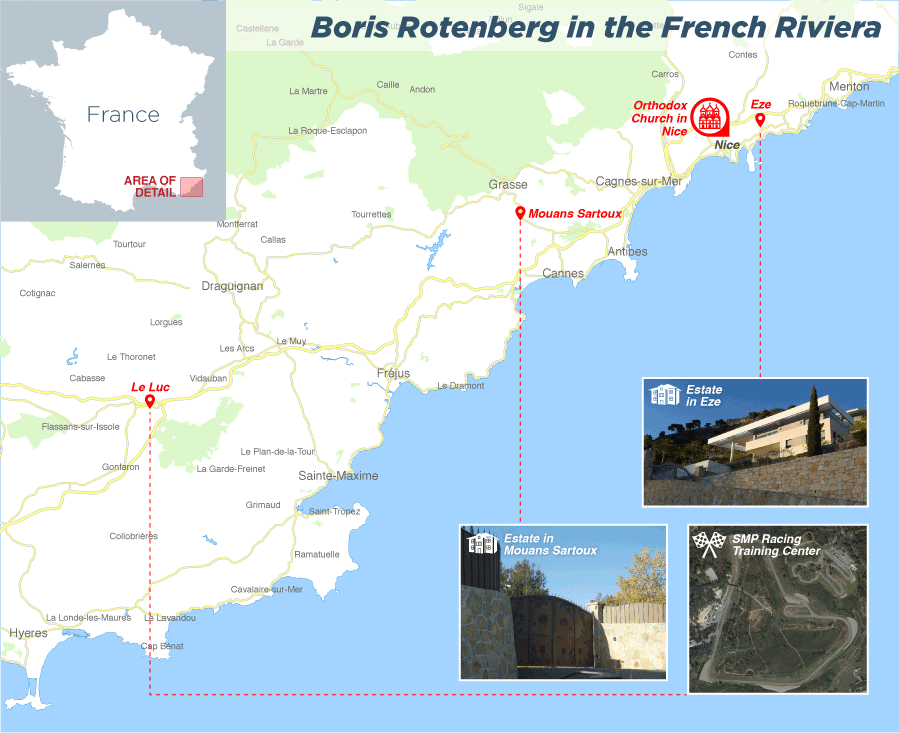

Boris Rotenberg in the French Riviera. Click to enlarge. (Edin Pasovic, OCCRP)These include a previously unknown multi-million-euro property containing two large villas — and plans for a third — in the picturesque seaside municipality of Eze.

Boris Rotenberg in the French Riviera. Click to enlarge. (Edin Pasovic, OCCRP)These include a previously unknown multi-million-euro property containing two large villas — and plans for a third — in the picturesque seaside municipality of Eze.

Rotenberg also makes use of another estate in nearby Mouans-Sartoux, which, as it turns out, is held through an opaque ownership structure that involves a company based in Monaco. A horse breeding company, registered at the same address in Mouans Sartoux, also belongs to the oligarch and his young wife Karina.

These European assets highlight the degree to which, even with sanctions in place, oligarchic Russian wealth has entrenched itself into some of Europe’s most desirable destinations.

Rise of the Rotenbergs

With respective fortunes estimated at US$ 1.2 and $3.1 billion, Boris and Arkady Rotenberg have come a long way from the chain of gas stations they ran during Russia’s period of cowboy capitalism in the 90’s.

Boris Rotenberg. (Photo: A Savin. Wikimedia Commons.)The Rotenbergs’ relationship with president Putin was almost certainly a crucial factor in their rapid success. The friendship goes back to the men’s childhoods, when they practiced judo together in what was then still called Leningrad. The trio remained close, and when Putin became president in 2000, the Rotenbergs became part of his inner circle.

Boris Rotenberg. (Photo: A Savin. Wikimedia Commons.)The Rotenbergs’ relationship with president Putin was almost certainly a crucial factor in their rapid success. The friendship goes back to the men’s childhoods, when they practiced judo together in what was then still called Leningrad. The trio remained close, and when Putin became president in 2000, the Rotenbergs became part of his inner circle.

That’s what jump-started their rise to the top.

A bank they founded in 2001, SMP Bank, is now one of Russia’s 30 largest, according to the its website.

But the Rotenbergs’ main gains have come from government contracting. In 2008, Arkady purchased five construction and maintenance companies from Gazprom, Russia’s state-owned energy giant. He merged these into Russia’s leading construction group in the oil and gas sector, Stroygazmontazh (SGM Group), which since then has been among Gazprom’s key contractors winning many lucrative deals while avoiding competitive tenders.

Multiple cost overruns in these projects have profited the Rotenbergs while hurting Russian taxpayers. In a 2017 New Yorker article, Mikhail Korchemkin, a natural resources analyst, explains that Gazprom has “switched from a principle of maximizing shareholder profits to one of maximizing contractor profits.”

Indeed, SGM Group reported earnings of nearly $4.6 billion in 2015.

The Rotenbergs have made billions elsewhere, too. According to the US Treasury, their friendship with Putin netted them construction contracts worth more than $7 billion for the 2014 Winter Olympics in Sochi. The elder Rotenberg also won a major tender to build a new bridge between the Russian mainland and the newly-annexed Crimean peninsula (work continues on the project to this day).

The success of Arkady Rotenberg is reflected in his regular appearance in Forbes’ “Kings of the State Order” lists, which rank Russian businessmen by the total value of state contracts they’ve won.

Foreign sanctions struck the Rotenbergs in 2014, after Russia’s annexation of Crimea. The US Treasury acted first, sanctioning both brothers personally and then blacklisting their major companies, SGM Group and SMP Bank.

The EU instituted its own sanctions — but just on Arkady Rotenberg — that July. Around €30 million of his assets, including an upscale hotel in Rome and two villas in Sardinia, were seized by Italian authorities in September 2014, according to media reports.

A Little Place by the Sea

Boris, on the other hand, was left off the European sanctions list, leaving his investments undisturbed.

One of these, a Monaco-based endurance motor racing program called SMP Racing, which he founded, trains its competitors in the French city of Le Luc.

As it turns out, just an hour and a half away by car, in the seaside municipality of Eze, the Russian oligarch owns a 2.7-hectare property. According to a local construction company, Rotenberg’s getaway was valued at €25 million by Societe Generale, a French bank, in around 2008.

Located on the French Riviera between the cities of Nice and Monaco, Eze is known for its well-preserved medieval architecture and impressive sea views. The municipality is just a 30-minute drive from the St. Nicholas Orthodox Cathedral in Nice, a vestige of Tsarist Russia built in the early 20th century.

Rotenberg’s property boasts a swimming pool, a dormitory for housekeepers, and two villas that total 1300 square meters in size. Furthermore, municipal records show that Rotenberg had big plans for expansion. In November 2009, he obtained authorization to add a large third villa to the property, as well as the pool, a tennis court, and a private funicular.

Boris Rotenberg’s property in Eze, France. (Photo: Sophie Balaÿ)

Boris Rotenberg’s property in Eze, France. (Photo: Sophie Balaÿ)

According to the municipality of Eze, construction of the third villa began in 2009, stopped for a while for unknown reasons, and then restarted this January after being reauthorized in February 2015.

However, according to the local construction company, neither Rotenberg nor his wife Karina have been seen at the house in nearly a decade. Rather, the construction at the estate has been supervised by the couple’s assistant, a Ukrainian-born French citizen named Sergiy Pavlenko.

Pavlenko was at one point registered as director of SMP Racing France (a subsidiary of the SMP Racing in Monaco, which has since closed).

France’s national address book lists Pavlenko as registered at the Eze home, as well as in Nice and Grasse, a French Riviera town near which the Rotenbergs also have a significant presence.

The Mouans-Sartoux Fortress

Just across the street from Pavlenko’s home in Grasse, in the neighboring municipality of Mouans-Sartoux, lies Boris and Karina Rotenberg’s other French estate — a secluded property roughly 29 hectares in size, with the initials “K B R” monogrammed on the gates.

Boris Rotenberg’s property in Mouans-Sartoux, France. (Photo: Sophie Balaÿ)

Boris Rotenberg’s property in Mouans-Sartoux, France. (Photo: Sophie Balaÿ)

The property, which lies off an obscure side road, is concealed on all sides by walls and protected by cameras and floodlights stationed at regular intervals. It stands out both for its enormous size and for its secretive atmosphere in otherwise modest surroundings.

In a 2016 interview with Tatler, a Russian magazine, Karina Rotenberg described the role the estate (which she calls their “dacha,” or country house) plays in her and her husband’s lives, explaining that they split their time between Russia and nearby Monaco.

But according to municipal records examined by reporters, the ownership status of the Mouans-Sartoux estate has been rendered opaque by its foreign holding company. The estate is owned by a real estate firm called Tannor 2 that is registered in Monaco, a jurisdiction that forbids the disclosure of shareholders.

That’s why, though the property appears to belong to the Rotenbergs, it is impossible to determine its ownership conclusively.

Boris Rotenberg did not respond to requests for comment for this story. According to a source close to the family, they do not own the home outright, but rather rent it from an undisclosed landlord. The source said that, being an avid participant in European equestrian competitions, Karina keeps horses on the estate, as it is too expensive to transport them from Russia.

Though its owners cannot be determined, reporters learned that Tannor 2 shares its Monaco registration address with Getad, a company run by Edmond Patrick Lecourt, Luxembourg’s honorary consul in the country. That connection appears to be more than a coincidence: Lecourt appeared in Mouans-Sartoux in 2014 to apply for permission to begin a new round of construction on the Rotenbergs’ estate.

When contacted by reporters, Lecourt declined to comment on his relationship with the Rotenbergs, only confirming that Getad provides Monaco addresses for companies wishing to register there.

Stables and Bank Vaults

Another Rotenberg connection to the Mouans-Sartoux estate also concerns Karina Rotenberg’s passion for horses.

As it happens, a French company called Societe Civile d’Exploitation Agricole des Canebiers (SCEA des Canebiers), which claims in its official filings to be involved in horse breeding and trading, is registered at the estate. The company is believed to be owned by the Rotenbergs.

Yet its ownership is not exactly straightforward.

One percent of shares in SCEA des Canebiers belongs to a Luxembourg-based lawyer named Michael Dandois who appears to have made a business of creating obscure corporate structures. His law firm, Dandois and Meynial, has worked with Mossack Fonseca, the firm at the heart of the Panama Papers leak.

The firm’s second shareholder, holding 99 percent of its shares, is a company called EQUUS, which is owned by Boris and Karina Rotenberg. According to the registration documents, the couple employed Dandois as a director of the company in 2013.

When contacted by reporters, Michael Dandois refused to comment on the arrangement or on the reasons behind it.

Boris’s wife Karina Rotenberg was once the director of SCEA des Canebiers herself, but in January 2014, two months before Boris Rotenberg was sanctioned by the US, she was replaced by Sergiy Pavlenko, the couple’s Ukrainian-born assistant and sometime property manager. That March, Pavlenko was also named director of SMP Racing France, a position he held until the company closed in April 2017.

Offshore holding structures of the type used by the Rotenbergs can offer certain benefits. Beyond ensuring confidentiality through opacity, the tactic of registering a real estate company in Monaco could be part of a tax savings or avoidance strategy.

“If there is a complex chain of interlocking offshore companies, there is a fair chance that the French tax authorities won't find the true beneficial owner and will just stop their research — especially when companies use proxies. So there might be a strategy of avoidance of the special wealth tax in this case,” said a French tax lawyer who asked not to be named.

One possible reason to register a company at a French address held by a Monaco-based firm may be to generate false expenses that could be declared as an offset against taxation. In this case, the owner would rent the land from the Monaco company through the French company, which would then declare the rental payments as a cost of doing business, entitling it to claim them against taxes owed to the French state. The expenses would then count as revenue for the entity in Monaco, taking them out of French jurisdiction and safeguarding them against French taxation.

If the intention behind these corporate arrangements is to purposefully obscure Boris and Karina’s finances, it would not be the first time a Rotenberg’s attempt to hide assets has come to light. In 2015, Offshore Leaks, a dataset of 100,000 offshore entities released by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ), revealed that some of their money had been channeled out of Russia into companies registered in the British Virgin Islands — three connected to Arkady and three to Boris.

Despite his close relationship to the Russian president and the fantastic wealth he has earned — partly the result of a major Crimean infrastructure project — Boris has retained the full enjoyment of his French investments.

In 2017, Forbes reported that it was his previous marriage to a Finnish woman — and thus his Finnish citizenship — that has enabled Boris Rotenberg to avoid being subject to the sanctions that were applied to his brother. However, in a statement given to Finnish news agency STT in March 2014, Finland’s then prime minister Jyrki Katainen said that Finnish citizens were not automatically protected from such sanctions.

The true reason for Boris’s lucky exemption, and why he is allowed to continue to do business in Europe, remains unclear.

When asked whether Boris Rotenberg faces any potential risks due to his ownership of property in France -- given the high-profile arrest last November of Russian oligarch Suleyman Kerimov in connection with his luxury properties in the country -- a person close to the oligarch replied, “they’ve lived under these circumstances since 2014. Every avenue which could have been closed to them has already been closed. From a legal perspective, there’s nothing more which can be done.”