Montenegrin crime boss Radoje Zvicer was scampering back to his Kyiv apartment with his kids to escape a spring rainfall last year when shots rang out.

Zvicer, who leads Montenegro’s Kavač cocaine-trafficking clan, barely survived the attack, taking five bullets to his arms and chest. His dog and three children escaped unharmed.

The family may owe their lives to the quick reaction of Zvicer’s wife, Tamara, who was nearby and packing a pistol. She fired at the hitmen and they ran to their getaway vehicle, a Smart car, and sped off before burning the vehicle and fleeing Kyiv.

A special police unit caught up with the gunmen outside the southern Ukrainian city of Odesa the following day, May 27, 2020, on their way to cross the nearby border into Moldova. Ukrainian national police announced that they had arrested four men — but images showed five people detained.

Journalists from OCCRP’s Ukrainian member center, Slidstvo, tracked the elusive fifth man to Kyiv, where they discovered he is a policeman. Court records show he was, in fact, one of three officers — including the city’s assistant police chief — who helped Zvicer’s would-be killers get into Kyiv, then flee after the failed hit.

They remain in their jobs, and have escaped charges over their roles in the attack. All of them declined to comment for this story.

Drawing on court records, police documents, and interviews, Slidstvo and OCCRP’s Serbian member centre, KRIK, pieced together the inside story of the attempted assassination, which was allegedly ordered by the Serbian boss of a band of thieves known as the “Pink Panthers,” and carried out by Balkan hitmen.

The attack on Zvicer was the latest salvo in a bloody feud between the Montenegrin Kavač and Škaljari crime gangs that has claimed at least 50 lives in just a few years. A previous investigation by OCCRP and its member centers uncovered a trail of bodies stretching across Europe, from Greece to the Netherlands.

"The attempted murder of Radoje Zvicer in Ukraine is just a continuation of the conflict between the Kavač and Škaljari clans, which has taken many lives both in Montenegro and in European countries,” Aleksandar Bošković, a Montenegrin police officer who heads the Department for the Suppression of General Crime, told Slidstvo in a documentary about the murder case.

Both criminal clans hail from Kotor, on Montenegro’s Adriatic coast. They were once part of the same gang smuggling drugs from South America, but they split in 2014 after a cocaine deal went bad. This created a violent rift that has deepened ever since — and pulled in other Serbian and Montenegrin crime groups.

With the cocaine war raging, Kavač crime boss Zvicer moved his family from Montenegro to Kyiv in 2019. But just a year later, the violence caught up with him.

‘Nothing to Talk About’

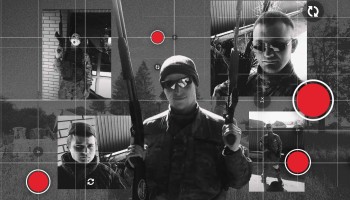

The trial of the men who are accused of trying to kill Zvicer — Serbians Petar Jovanović and Milan Branković, and Montenegrins Emil Tuzović and Stefan Djukić — began in Kyiv in May.

All four of them have a criminal past. Branković’s rap sheet includes a conviction for attempted murder, while Jovanović, who has previously been convicted of robbing a bank, is also suspected of killing an associate of the Kavač clan in Belgrade in January 2020.

Police say both of the Montenegrins were affiliated with the Škaljari clan. Montenegrin police officer Aleksandar Bošković said Tuzović has a criminal history, while Djukić is facing charges for killing a man in Montenegro in 2019.

It’s unclear how much of this Kyiv Assistant Police Chief Yevhen Deidei knew when he agreed to help them. The 33-year-old officer — who’s also a former member of parliament and a veteran of the war in eastern Ukraine — admitted to investigators that he had arranged transport for the suspects. But he said he had no idea what their mission was.

Deidei told investigators he had helped the four men get to Kyiv because a friend of his from Poland asked him to. The friend, whose name he gave only as Maček, apparently sought his assistance because public transport had been halted due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Deidei did not explain why Maček needed to bring these men to Kyiv, but said he asked two of his officers, Rostislav Chernobrovyi and Semen Hordienko, to collect them.

"After Hordienko and Chernobrovyi brought Maček’s acquaintances to Kyiv, Semen [Hordienko] called me and said that they had fulfilled my request," Deidei told investigators.

Deidei did not offer any further information about Maček, and he denied any knowledge of the plan to kill Zvicer. But details obtained by journalists show other links between him and the attempted assassination.

For one thing, a law enforcement document shows he received a WhatsApp message about eight months earlier from a different friend, asking him to check if the Zvicer family was in Ukraine.

Journalists also traced the license plate of the Toyota Sequoia SUV that police say Gordienko and Chernobrovyi used to transport three of the alleged killers to and from Kyiv. The owner of the vehicle turned out to be an acquaintance of Deidei, who sold it a few months after the attempted hit.

After illegally crossing into Ukraine's Chernivtsi region, Jovanović, Branković, and Tuzović were first met by two men in a gray SUV, who later told investigators that Deidei gave them instructions on where and when to meet the alleged hitmen. The two drivers transported the suspects a short way to meet Chernobrovyi and Hordienko, who were waiting in the Toyota Sequoia to take them on the 500-kilometer journey to Kyiv.

The fourth member of the alleged hit squad, Djukić, was waiting for them in Kyiv, having already come to Ukraine two months earlier using a fake passport from North Macedonia.

Two of the men went to an apartment that had been rented for them in the same complex as Zvicer’s family, while the other two appear to have stayed at a separate apartment in another part of the city. Once in Kyiv, they watched their target and obtained weapons and the Smart car, which police suspect was purchased by an unknown individual using a stolen passport.

Two weeks later, they allegedly attempted to murder the Kavač boss, pumping five bullets into him in the middle of the day in a Kyiv suburb, as his children scattered.

After the would-be killers made their escape, they hurriedly tried to destroy the evidence by burning the Smart car. Footage collected by police shows one of the men running from the car with his clothes on fire after spilling gasoline on himself.

Chernobrovyi and Hordienko then picked up the team in the Toyota Sequoia and drove them to the outskirts of Odesa, where they were caught by police.

Chernobrovyi and Hordienko refused to comment for this story. But journalists managed to reach Chernobrovyi right after the arrests last year. He denied it was him in police photos being detained along with the suspects in Odesa.

During the investigation, however, Hordienko told police that Deidei had given him and Chernobrovyi the times and locations to pick up the suspects and bring them into and out of Kyiv.

Deidei refused to comment when journalists questioned him outside Kyiv police headquarters. "I have nothing to talk about," he said as he rushed past them and got into a vehicle.

‘Pink Panthers’

Documents from an investigation by Serbian prosecutors indicate that the attempt on Zvicer’s life was ordered by a man named Milan Ljepoja from Niš, a city in southern Serbia. Ljepoja led a group of burglars known as the “Pink Panthers,” which appeared to be aligned with the Škaljari, who are rivals to Zvicer’s Kavač clan.

Ljepoja was sentenced to prison for nine years in 2010 by a Liechtenstein court after his Pink Panthers were caught stealing more than a million Swiss francs worth of jewelry. But he was sent home to Serbia in 2013 to serve out the rest of his term.

Ljepoja disappeared late last year and the Serbian Prosecutor's Office for Organized Crime believes he was murdered by another gangster, Veljko Belivuk, although his body has not been found.

In their investigation into crimes allegedly committed by Ljepoja’s group, Serbian police tapped the phones of members of the criminal organization led by Belivuk, a Kavač ally. KRIK obtained transcripts of the wiretaps, which include conversations suggesting that Ljepoja ordered Zvicer’s killing.

In one recording, an associate of Belivuk’s from Niš named Marko Andrić said one of Ljepoja’s men told him that the Pink Panther boss, who was also known as “Mance,” sent someone to Kyiv to kill Zvicer.

"I'm sorry for what he did to Zvicer up there, after Mance organized everything," said Andrić, according to a transcript of the wiretaps.

As for Zvicer himself, Ukraine authorities want him to testify against the men who allegedly tried to kill him, while both Serbia and Montenegro issued warrants for his arrest earlier this year.

But the crime boss has disappeared.