Every national tragedy is also a human tragedy.

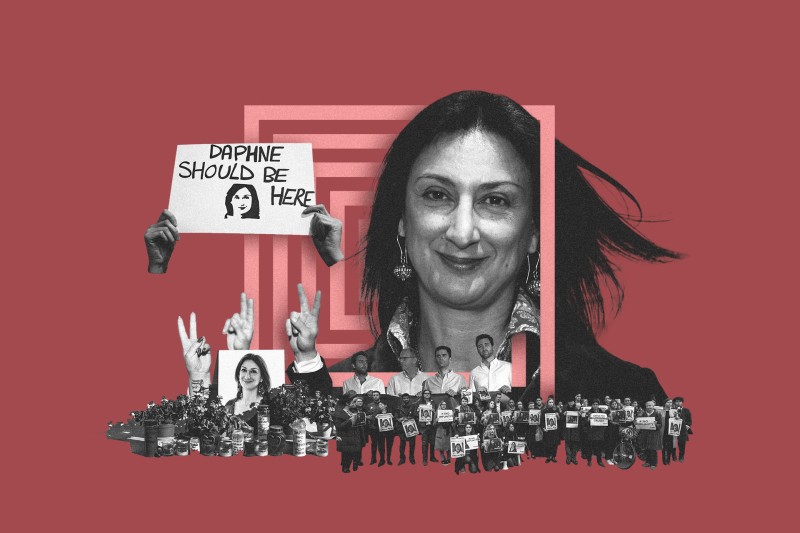

On the fifth anniversary of Daphne Caruana Galizia’s brutal murder, it’s worth remembering that, before the investigative journalist was mourned by thousands across Malta, she was first mourned by her family.

“She was totally full of life,” remembers her sister, Corinne Vela. “People wouldn’t know how creative she was, how big a life she had behind her blog. … She produced a wonderful magazine, full of beautiful things, beautiful interiors, and wonderful food. The good things in life.”

Her son Matthew recalls her passion for archeology. “That was her first university degree, which she did in her thirties,” he says. “My brothers and I would follow her to her lectures like three little ducks.”

“When I was a bit older, I’d go on digs with her. Each one felt like a big adventure. Uncovering something that no one had seen for thousands of years was a big thrill, but even better was hearing my mother's explanation of what it was and how it got there.”

A family photo from the early ‘90s of Daphne Caruana Galizia with her three young sons.

Later, she turned that passion for uncovering layers of history to another field: investigative journalism. She worked as a reporter and columnist for decades, but it was her investigative blog, “Running Commentary,” that made her famous.

Full of stories about high-level crime and corruption, interspersed with acerbic quips and insults, it reportedly had more readers than any of the country’s newspapers. Many Maltese recalled that reading it was the first thing they did every day.

But five years ago, on a Monday afternoon, it was all snuffed out. The 53-year-old journalist was late to a bank appointment. She had just run out of the house, promising Matthew she’d be back in a couple of hours.

“I pressed ‘resume’ on the laptop to continue playing the music I was listening to,” he remembered. “And then I heard an explosion. And I knew it was a car bomb, straight away.”

The scene he found outside was a horror: his mother’s car aflame, her body parts scattered across the ground.

“When I was circling the car, I just thought: Those bastards,” Matthew said later. “She was obviously killed because of something she had written about.”

This is where the family tragedy turns national. Caruana Galizia wasn’t just an investigative journalist: In Malta, she was the investigative journalist.

In maintaining “Running Commentary” — and, unusually in Malta, daring to sign it with her name — Caruana Galizia set herself against a long-established system of entrenched power and privilege. She fought it all her life, enduring harassment, arson attacks, the murder of her dogs, and dozens of libel suits.

Some of these — including those filed by former Prime Minister Joseph Muscat and former Tourism Minister Konrad Mizzi — continue even today. When her name rings out in court, it is a grieving member of her family who has to answer.

Caruana Galizia’s supporters point to these ongoing lawsuits as a sign of how deeply she is still hated, even after her death, by the subjects of her journalism.

It is no wonder. Her voluminous posts frequently targeted Muscat and other top officials, alleging opacity, corruption, and a culture of impunity at the highest levels of the Maltese state. Among the topics she covered in her last years was a scheme set up by Muscat’s government to sell Maltese passports to wealthy foreigners, suspicious offshore companies set up by top members of his government, and a minister’s alleged visit to a German brothel.

And though she was not able to finish all of this reporting before her death, her work was continued by a consortium of outlets, including OCCRP, led by French journalism group Forbidden Stories.

Unsurprisingly, pursuing her leads led to multiple big stories. The passport scheme she investigated was investigated for kickbacks; Muscat’s chief of staff was charged with money laundering, fraud, and corruption relating to a case she had reported; and a bank she covered was used for money laundering by the daughters of Azerbaijani dictator Ilham Aliyev.

In addition, Caruana Galizia had alleged that an Emirati company called 17 Black was used by top officials to move illicit money, though she was unable to discover the details or to find out who was behind it.

It later emerged that the company belonged to Yorgen Fenech, a well-connected businessman who won a stake in a concession to build a major new power plant. Leaked emails revealed that 17 Black was set to send money to Panamanian offshore companies belonging to Muscat’s chief of staff, Keith Schembri, and then-energy minister, Konrad Mizzi — who had been instrumental in promoting the power plant concession.

In the face of these entrenched, powerful interests, the pursuit of justice for Caruana Galizia’s murder — and of a reckoning with the corruption she dedicated her life to exposing — has been a long and difficult battle.

The most important successes over the last five years have been made possible by several factors: relentless campaigning by press freedom organizations, activism by outraged Maltese citizens, and attention from top European leaders.

But at the center of it all was Caruana Galizia’s family. In a sense, it was only by turning their personal tragedy into a public one — from a private grief into a civic cause — that they managed to eke out some important victories.

From the beginning, the family focused on getting the government to launch an independent public inquiry into her killing and the culture of impunity that made it possible.

The headwinds were strong. In Malta’s polarized political landscape, the ruling Labour Party and its supporters were resistant to any attempts at accountability. Even a memorial set up by supporters in front of the Court of Justice was dismantled every night by government employees.

So the Daphne Caruana Galizia Foundation, established by the journalist’s family after her death, led a fierce campaign that engaged the European Parliament, the European Commission, the Council of Europe, and other international institutions.

The fight was joined by press freedom organizations like Reporters Without Borders, Article 19, and the Committee to Protect Journalists. At home in Malta, new civil society groups pushed for accountability.

Free expression and anti-corruption organisations pay tribute to Daphne Caruana Galizia with a protest outside Malta House in London, demanding the authorities in Malta to bring her murderers to justice.

Finally, in September 2019, responding to pressure on multiple fronts, the Maltese government announced an independent inquiry into Caruana Galizia’s killing. It took continued campaigning and a prolonged period of negotiation — described by her family as “one of the most painful fights we have ever fought” — before the standards of that inquiry were adjusted to make it fully independent, public, and comprehensive.

Even then, the battle wasn’t over. Even as it received written and oral testimony from nearly 150 witnesses, including members of the family, journalists, officials, and civil society groups, the inquiry was dogged by understaffing and low resources: It had no lawyers or investigators, was not live-streamed, and did not even have a website. The family and its supporters had to keep campaigning, in the face of a smear campaign driven by pro-government media and picked up on social media by abusive trolls, to ensure it would proceed independently and not be shut down prematurely.

Despite these challenges, the inquiry was a landmark. Led by one sitting judge and two retired judges, and enjoying the power to compel witnesses to give evidence, it kept the case and the larger issues behind it — impunity, problems with rule of law, and media freedom — on the front pages.

Its conclusions, published in a 435-page report last July, were damning. The report — which was [released only in Maltese](https://www.gov.mt/en/Documents/DCG final version as at 12.08.2021.pdf), with the foundation paying for an English translation — found that Caruana Galizia’s murder was linked to her journalistic work and that the government bore responsibility for the environment in which it occurred, having created “a climate of impunity, generated from the highest levels at the core of the administration … and spreading its tentacles to other entities such as regulatory institutions and the Police.”

It singled out Muscat for facilitating this climate, which was “relied upon by the elements of organized crime, whoever they were, and which certainly facilitate the assassination.”

The inquiry also made a number of recommendations, including reforming laws on media, financial crime, obstruction of justice, and abuse of office; strengthening protection for journalists; addressing the problem of abusive lawsuits against them; and constitutionally recognizing independent journalism as a pillar of democratic society.

“The public inquiry was the one hard thing we campaigned for,” says Rebecca Vincent of Reporters Without Borders. “If its recommendations are implemented properly, it could be a model for other countries dealing with such situations.”

But now that the inquiry is over, the implementation of these measures is in the hands of the Maltese government. And that is where the Caruana Galizia family’s struggle continues today.

For a while, it seemed like the public outrage over her murder might be enough to prod the government into meaningful action. While the inquiry was still in its early stages, Malta was shaken by unprecedented public protests. In November 2019, Fenech, the businessman with the power plant concession, was arrested on his yacht on suspicion of masterminding Caruana Galizia’s murder. Furious demonstrations erupted the following day and lasted for weeks, spurred by Prime Minister Muscat’s failure to dismiss his corruption-tainted subordinates. As a result, Muscat, Mizzi, and Schembri all resigned.

A protest in Malta after Caruana Galizia’s death.

But a system like Malta’s doesn’t change overnight, or even in a few months. Muscat’s successor as prime minister, Robert Abela, has argued that there is “no impunity” in Malta and, while repeatedly apologizing to Caruana Galizia’s family, has not committed to a comprehensive implementation of the inquiry’s recommendations.

Earlier this year, a bill introduced by the opposition based on the public inquiry’s recommendations was defeated by the governing Labour Party. A few months later, Labour was reelected to a third term, with opinion polls pointing to the public’s approval of the government’s handling of the COVID-19 pandemic and its stewardship of Malta’s growing economy.

“[Prime Minister] Abela has in many ways tried to distance himself from his predecessor,” Vincent says. “But it’s the same government with new faces. … It boils down to political will. After five years of working closely on this, my categorization is that the government lacks the political will needed to ensure that this does not happen again.”

Corinne Vela, Caruana Galizia’s sister, is also frustrated by the lack of progress. “There is no public acknowledgement that the state has failed,” she says. “It’s like the public inquiry is just another report. We’ll tick a few boxes and be done with it.”

She and the rest of the family are determined to press on, heartened to see civil society awakened to the country’s deep-rooted problems. “From the first moment, we knew we were in this for a long time, and there would be no time to grieve,” she says.

For justice to be done in Malta, the personal will have to remain political for a long time to come.

OCCRP is collaborating with the Daphne Caruana Galizia Foundation to train local journalists in investigative reporting.