It’s no surprise that a leak of data from a major Swiss bank like Credit Suisse would reveal accounts belonging to famous billionaires, well-known oligarchs, and other prominent characters from around the world.

But in Uzbekistan, the Suisse Secrets data also revealed a puzzle: An account, holding nearly $1 million, that belonged to Rano Ramatova, a completely unknown Uzbek woman who appeared in no public records.

The power of attorney over that account, meanwhile, was held by one of the country’s most powerful business operators. Payzullajon Mirzaev is a co-founder of the Orient group of companies. This conglomerate, one of Uzbekistan’s largest, has interests in everything from banking to construction to agriculture. It’s also a key partner of the railway company and its companies have imported steel, built railway lines, and supplied railway ties.

Why would this busy man be entrusted with an account belonging to an unknown woman?

As it turns out, Ramatova is not a nobody. Though her name has never emerged in public, OCCRP reporters learned that her husband is Achilbay Ramatov, Uzbekistan’s first deputy prime minister and the former head of O’zbekiston Temir Yo’llari, the state railway company.

This represents a glaring conflict of interest: During the same years that Ramatova’s Swiss account was open, between 2010 and 2015, the railway company her husband led was awarding contracts to Orient Group.

There’s no direct evidence that the money in Ramatova’s account represented a kickback, bribe, or any other illegal payment, though it had been rumored for years in the local press that Mirzaev, the Orient Group co-founder, was her husband’s secret financial backer.

Achilbay Ramatov (left) and Payzullajon Mirzaev (right) during a visit of Uzbek president Shavkat Mirziyoev to Bektemir Metal Construction factory, which is co-owned by his son-in-law’s brother.

There is also another connection between Ramatova and Mirzaev.

This one comes from the Pandora Papers, a separate leak of millions of records from a set of offshore service providers that was obtained by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists and shared with OCCRP and other media partners.

According to the documents, Ramatova was the owner of an offshore company set up in the British Virgin Islands (BVI). When she set it up, she said her income came from co-owning businesses in Uzbekistan that import steel, build railway lines, and supply railway ties.

She didn’t name the businesses or their co-owners, and reporters couldn’t find any registered businesses owned by Ramatova.

But it is clear she had close ties to Orient. When Ramatova’s company was investigated for money laundering in 2015 Orient Finance and Orient Building submitted letters in support of her. Both letters described Ramatova as a “valued client.” (Confusingly, when contacted by reporters, the Orient Building lawyer who had written the letter said that Ramatova had been an “employee” of the company. He did not respond to subsequent requests for more information.)

The results of the money laundering probe are unknown. But once Ramatova’s registration agent was notified of the investigation, her Credit Suisse account was soon closed and her company shut down the next year.

Kristian Lasslett, Professor of Criminology at Ulster University and Co-Director of UzInvestigations, which published a detailed report into Orient Group and its links to political figures, said that these findings fit into the larger picture in Uzbekistan of “authoritarian power being used as a tool to carefully curate business empires for those who are controlling levers in the government.”

“It is very well established that Orient Group is highly politically exposed to a number of powerful families in the political infrastructure in Uzbekistan,” he said. “They also have … shady relationships with the national railways, [which are] … long suspected of being highly corrupt.”

In the railways, Lasslett said, “you have the extremely problematic situation of large contracts being given for direct purchase to companies that are politically exposed to senior officials, who are potentially hidden shareholders or hidden beneficial owners.” “In that context, there is every reason for the public to say: Is this corruption? Is this a conflict of interest? Is this people using their political power to fix contracts that have been given to their own business groups?”

A railway platform in Uzbekistan’s capital of Tashkent.

Neither Ramatov nor Mirzaev responded to requests for comment for this story. Ramatova said that OCCRP’s claims were not confirmed by documents in her possession, but provided no evidence. She then went silent.

On February 22, after OCCRP published an interactive feature that included Ramatova among Credit Suisse’s dubious clients, a news site called Daryo.uz reported that it had received a comment from Ramatov: He denied that any members of his family had bank accounts abroad, and asked media not to spread “false information.”

The Suisse Secrets Investigation

Suisse Secrets is a collaborative journalism project based on leaked bank account data from Swiss banking giant Credit Suisse.

The Rise of a Quiet Official

Not everyone gets a birthday greeting from their favorite soccer team. But in August 2017, the players of Uzbekistan’s Lokomotiv Tashkent — a team founded by the state railway company — went all out to congratulate one of their country’s top officials on his 55th birthday.

In a video posted on YouTube, the players stood on the field in the form of a 55, clapped, and chanted “Congratulations!”

Lokomotiv Tashkent players congratulate Achilbai Ramatov on his 55th birthday in this YouTube video.

Lokomotiv Tashkent players congratulate Achilbai Ramatov on his 55th birthday in this YouTube video.

The recipient of their well-wishes was Achilbai Ramatov. Less than a year earlier, he had received a big promotion, becoming the country’s first deputy prime minister.

A career state official, Ramatov spent most of his adult life working in the transportation sector. From 2002 to 2019, he led the national railway — and even continued to do so for a little over two years after he was promoted to his deputy prime minister position.

For most of his career, Ramatov was hardly a public figure, but his work was critical to the economy in Uzbekistan, a land-locked country that depends on its railway system for imports and exports. During Ramatov’s 17 years at the helm, the country added new routes and trains and launched the first high-speed rail system in Central Asia. Ramatov’s rare appearances in the news were usually connected to such achievements.

He also faced criticism, especially after his profile rose with his promotion to first deputy prime minister When a newly built dam burst in May 2020, killing several people and flooding thousands of homes in Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan, Ramatov took some of the blame: Uzbeks complained that he had been distracted by having two jobs at the same time.

But despite his rising visibility, Ramatov managed to preserve one thing from his previous life: secrecy about his family. For years, Uzbek media have only reported that he was married and had three daughters. Everything else about them remained a mystery.

The Samarkand railway station.

Offshore Maneuvers and a Money Laundering Investigation

The experience of post-Soviet countries with high levels of corruption — places like Russia, Kazakhstan, and Kyrgyzstan — shows that top officials sometimes keep their wives or partners secret for a specific reason: they are often tasked with holding the family’s wealth, especially if it can’t be easily explained.

Rano Ramatova, the first deputy prime minister’s wife, likely falls into this category. In addition to the $1 million she held in a Swiss bank account, she owned an offshore company in the British Virgin Islands that appears to be connected to the state railway company run by her husband.

In February 2010, a company called Keltran International Limited was registered in the BVI. Though Ramatova was Keltran’s beneficial owner — the person who stands to benefit from a company’s activities — she did not personally hold shares in the company. Instead, the shareholder was yet another offshore company, suggesting that steps had been taken to disguise Ramatova’s connection to Keltran. OCCRP only learned of the company through the Pandora Papers.

In the questionnaire required to open her company, Ramatova claimed that her income came from co-owning businesses in Uzbekistan involved in importing steel, building railroad lines, and supplying railway ties. OCCRP was unable to find any Uzbekistani business owned by Ramatova, but if she did work in these areas it would represent a serious conflict of interest, given her husband’s position.

According to Keltran’s paperwork, the company’s purpose was to “hold funds for investment in various securities.” It also authorized a vice president of Clariden Leu, an exclusive Swiss private bank, to give instructions on company administration.

Though it’s unclear how much money passed into Keltran, the documents show that, for a few years, the company had a relationship with Clariden Leu that included an “investment portfolio agreement,” meaning that the bank would invest money on Ramatova’s behalf. The documents also show that Keltran held a bank account with another Swiss lender, Falcon Private Bank.

A Spacious Moscow Office

Ramatova’s account at Credit Suisse was opened a few months after Keltran was registered. It was held through an unknown legal entity — quite possibly Keltran, especially considering that Clariden Leu later merged into Credit Suisse. According to leaked Suisse Secrets data, the account reached its maximum balance of nearly $1 million in July 2012.

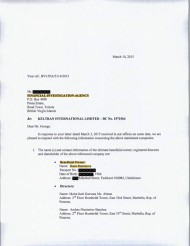

In 2015, Keltran’s registered agent — the firm that handled its paperwork — received a letter from the BVI Financial Investigation Agency, seeking information as part of a money laundering probe into the company. In response, the registration agent confirmed that Ramatova was Keltran’s beneficiary, provided documentation about the company’s directors, and — as explanation of what due diligence they had undertaken — provided several letters of reference for Ramatova.

One of these was from the Clariden Leu vice president who had been in charge of her account.

Two others came from Uzbekistan, each from a company within the Orient Group. The letters, which described Ramatova as a “valued client,” said she had been doing business with Orient for years. The dates they were written — shortly after the Financial Investigation Agency notification — strongly suggest they had been solicited specifically for the purpose of defending Ramatova, and not as part of an earlier due diligence effort.

Orient Group, of course, is the Uzbekistani conglomerate that received state contracts from her husband and whose founder had power of attorney over her Credit Suisse account.

Soon, both Ramatova’s company and her account were closed.

Ramatova’s Keltran Connections

Business With Orient

In recent years, Orient Group has advertised itself as a major partner of the Uzbek railways in building Uzbekistan’s transportation infrastructure.

In fact, the conglomerate’s dealings with the railway began years ago — and, during the period Ramatova held her Credit Suisse account, much of its business was in the very same areas indicated in her offshore documents.

A company within the group, Orient Mebel (“Orient Furniture”), began by importing railroad switches into Uzbekistan in 2008, and continued to import other railway infrastructure components over the following years. These included railway ties, a segment of the business Ramatova’s offshore documents indicated as a source of income.

Orient workers on the job.

Orient Building, the company that wrote her a letter of reference in 2015, imported steel into Uzbekistan in 2012, just as her documents said she did.

In 2011, Orient Finans Bank — the other company that would later write a letter of reference for Ramatova — became the sponsor of Lokomotiv Tashkent, the football team founded by the railway.

Orient Group also expanded its logistics business in partnership with the railway, completing a modern logistics center in Tashkent in 2014. Since then, it has expanded that center and built two more container terminals in the city.

The conglomerate now promotes the railway as one of its main partners in transport infrastructure projects. One Orient company in the group was specifically founded to do business with the state firm.

Another Well-Connected Co-Founder

In addition to Mirzaev, Orient Group has a more publicly visible co-founder, Saken Polatov. Two of his non-business endeavors — boxing and soccer — tie him closely to Ramatov, until 2019 the head of one of his major clients.

The Orient Group has also carried out another high-profile commission, this one for the president himself. In February 2021, Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty published an Uzbek-language investigation revealing the existence of a secret palace built for President Mirziyoyev, a mansion located in a nature reserve.

The journalists reported that it was built on land belonging to the state railway company, and Ramatov himself helped manage the construction. The contractors were reportedly Orient Group companies. One of them, which is co-owned by Oybek Umarov, a brother of the president’s son-in-law, provided cement and metal for the construction of the mansion, according to RFE/RL.

OCCRP repeatedly sought comment from the Ramatovs for this story but received no response.

Two weeks ago, however, reporters got a different kind of answer. An article called “Uzbekistan in the Crosshairs: OCCRP Prepares New Investigation” appeared in an obscure media outlet called EADaily.

Citing “presidential administration” sources, the article describes OCCRP as a scandalous propaganda outlet with military and CIA connections that has waged information warfare against Russia — and is now training its sights on Uzbekistan.

The story contained no specific threats. But it was soon republished under a more ominous title: “Milkers on Payroll Will Be Grabbed By The Udders.”