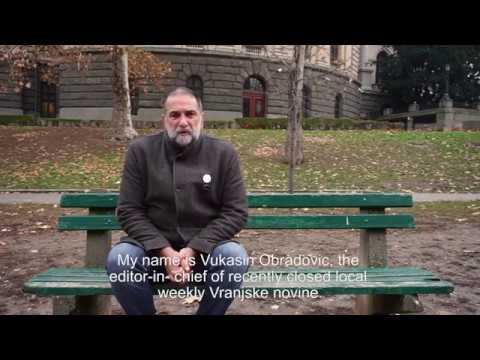

One day this September, Vukasin Obradovic entered the offices of Vranjske, a Serbian weekly, saw the reporters who had invested their lives into the publication – as well as his own 23 years of hard work - and realized: this is the end.

“I felt nauseous,” the editor-in-chief said. “You ask yourself: Was it all worth it?”

For 23, years Vranjske published stories almost nobody else would.

Even during the repressive regime of late Slobodan Milosevic, the paper, from the city of Vranje, wrote about war crimes committed during the Yugoslav wars of the 90s, embezzlement of public funds, sexual assaults within the Serbian Orthodox Church, drug smuggling, organized crime, and more.

But after the paper published an interview with a local whistleblower who revealed illegal hiring practices at the city’s tax administration office -- and covered the retaliation he faced -- it was sentenced to death.

It was the director of the office, Sladjan Tomic, who first revealed the illegal hiring practices to the paper. As soon as the interview was published, he was demoted and mobbed by the new director, Sladjana Stojanovic, a woman with allegedly good connections to the Serbian ruling party.

Tomic again turned to Vranjske and described what happened in a second interview published in July.

That’s when the tax inspectors arrived. They hardly left the paper’s offices for weeks, searching for any excuse they could find to close it down, or at least to make it pay a hefty fine that would force it to close down. They never found anything.

Obradovic knew where this was coming from and why.

In an open letter to the tax authority’s new director, he pointed out that his reporters were under pressure in retaliation for covering issues of interest to the citizens of Vranje. Because they were doing their jobs as journalists, he wrote, they were treated by the ruling party as political opponents.

But the inspections wouldn’t stop coming. Meanwhile, the publication’s landlord – the state pension fund – kicked it out after 15 years, and despite having scores of empty offices in the building.

All this came on the top of Vranje’s previous dispute with the local government over the allocation of funds meant to support Serbian media in early 2017.

After the municipality made a much-criticized decision to allocate most of the money to outlets believed to be controlled by the country’s ruling party, the Vranjske staff went on strike.

The paper was given such a ridiculously small amount of money that it returned the funds to the local government in protest.

By the end of the summer, the lack of funds, the eviction notice, and the tax inspectors -- who told the editor-in-chief off the record that they had been tasked with finding “something” -- prompted Obradovic to declare a hunger strike.

“Journalism and Vranjske cannot be separated from the rest of my life,” Obradovic wrote in a public letter. “I just don’t want turn away and move on peacefully from what I’ve been fighting for all this time,” he said.

Obradovic ended his hunger strike after just one day because of other health issues, but the pressure led to his decision to close Vranjske.

“It was a hard moment,” he told OCCRP. A moment in which he realized that all the good and bad times he and his colleagues went through, the mission that had brought them together, would all cease to exist because of one interview.

Obradovic was respected among colleagues around the country and was president of the Independent Journalists Association of Serbia. After his hunger strike, hundreds of journalists and citizens gathered in front of the Serbian Government building in Belgrade, protesting against what they saw as unacceptable government pressure.

“I Stand by Vranjske,” read their banners.

The Journalists’ Association said that closing of the weekly was a direct consequence of long-standing political pressures on media freedom and the corrupt media funding system.

More support came from the European and International federations of journalists. Both organizations said that they stood in solidarity with Obradovic and joined their affiliates in Serbia in denouncing the government’s oppression.

In the end, it made little difference. Vranjske remains closed. But people in his southern Serbian town still approach Obradovic and ask him when the paper would publish again.

“They can’t believe it,” he says. “I also catch myself seeing or hearing something and thinking, this would be a good story. Then it hits me again: Vranjske no longer exists.”

But the outrage the case prompted in Serbia grew into a new wave of resistance. Twenty-seven outlets throughout the country formed what they call the “Group for freedom of media in Serbia.”

Obradovic is a member.

“I hope we will move things, at least a milimeter,” he says. For a moment, hope lights up his face. Or is it spite?

“I’ve taken part in so many battles,” he says. “I can’t miss this one.”

This project is part of the Global Anti-Corruption Consortium, a collaborative effort between OCCRP and Transparency International to fight corruption by combining investigative journalism and grassroots activism.