On July 4, 2019, people across the United States celebrated Independence Day with fireworks, barbecues, and star-spangled flags.

That same day, three young men in their teens and early 20s — Sanjiv, Raja and Manpreet — left their village in northern India in pursuit of their own American dream.

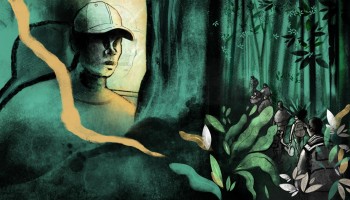

They had paid thousands of dollars to smugglers to transport them 13,000 miles across the world in the hope of making a better life in the U.S. They then spent months travelling on foot or by plane, boat, and bus, down rivers and through the jungle, crossing continents along the way.

But their dreams did not come true. The three migrants were caught and placed in a Mexican camp before they crossed the Rio Grande into the U.S. Three months after they left home, Sanjiv and Raja were deported to India, where they are now struggling to make ends meet.

Manpreet died at age 16 in a hospital near the camp, a 17-hour drive from Texas.

A few months after they were deported, journalists from The Confluence Media, working as part of an international consortium that includes OCCRP, met with Sanjiv and Raja near their homes in the Indian state of Punjab. Sitting in a roadside diner on the outskirts of Dharamkot, a farming village of 15,000 people, they described their journey to the other side of the world and back again.

This is their tale, though we have changed their names to protect them from possible reprisals.

No Jobs, No Money

Sanjiv and Raja, both in their early 20s, consider themselves best friends. They have known each other since childhood and went to the same school. They both wear similar outfits: a sporty jacket or sweatshirt, jeans, and flip-flops. They both also never seem to put down their cell phones.

The pair say they left Punjab because they could not find work in their agricultural community. Sanjiv explains he didn’t want to join the army and there were no jobs available in the civil service. Raja said he couldn’t even find a menial job to keep him going.

They decided their best hope was to pay smugglers between US$21,000 and $22,400 each to take them to the U.S. They scrimped, saved, and borrowed to find the money: Raja mortgaged his house for $7,000; Sanjiv sold his family’s home for about $10,000. Both were promised that in six weeks they would be on American soil.

“We sold a lot of things,” said Raja. “We were thinking that there are no jobs here. We looked for a long time and ended up spending a lot. I also asked my family for money.”

Both men went quiet and looked away when asked about the people who smuggled them. They declined to answer reporters’ questions, saying they didn’t want to jeopardize their chances of getting their money back.

Another migrant, however, told reporters the networks operate through local agents in Punjab, who recruit migrants, then pass them to national smuggling networks. He said the trade is coordinated by Indians living in Tapachula, in southeast Mexico, who work with accomplices in the countries along the route.

On U.S. Independence Day last year, Raja, Sanjiv, and their teenage friend Manpreet took a vehicle to the airport in Amritsar, the largest city in Punjab. From there, they flew to Dubai and finally to Armenia, where they waited for a month. Next their journey took them to Moscow, where they connected to Havana and then on to Panama.

They finally landed in Ecuador, where they could disembark without a visa, a few weeks later. But despite all their travels, more than 3,000 miles still separated them from the U.S. border.

So, they began to travel in secret. First they stopped in a city whose name they cannot remember, perhaps Quito. Then they traveled on to Cali in Colombia and then, after a journey of around 850 miles by road, arrived at Turbo on the Caribbean Sea. From there they crossed the Gulf of Urabá by boat and began the terrible trek on foot through the Darién jungles to Panama.

“It's very hot in the jungle, and people actually die from that. So many people are dying that we didn’t even think we were going to survive,” said Raja, remembering how they had no water for the first two days of the trip.

At one point, he said, he was drinking two Red Bulls a day to keep up his energy as he carried his pack through the sweltering heat. “Sometimes the mountains were too high and there we used to feel like we can’t continue,” he said.

“But our courage didn’t fail us, we kept moving and moving, and finally we made it to the camp. And then we felt relief.”

Detained in Mexico

Things went wrong for the three young men from Punjab as soon as they set foot on Mexican soil. Despite travelling in different groups, they all ended up in the Acayucan migrant holding center in Veracruz.

Acayucan is an imposing walled building, guarded by white steel bars and armed federal police officers who stop anyone entering except staff and busloads of migrants. The site is only meant to house 836 people, but more than 3,000 men, women, and children were crowded inside last July. By the time the trio arrived, that figure included over 500 Indian migrants.

In the camp, people were kept in small cells measuring just six square meters, with concrete slabs to sleep on. Their only glimpse of the outside world from their rooms is through barred windows. The showers and bathrooms had no doors or curtains.

“In the camp there were no clothes, no bathing facilities.... They only gave us food once or twice a day. It wasn’t good,” said Raja.

Sanjiv remembers that there were mosquitoes, it was cold, and the camp staff neglected people who were sick.

Their accounts are backed up by a 2017 report from the Mexico-based Institute for Security and Democracy, which found migrants in Acayucan were living in unsanitary conditions with bathrooms full of waste and mattresses infested with bedbugs. In the heat of the summer, the report warned, temperatures in the camp rose to more than 30 degrees Celsius.

Mexico’s government announced last year it had spent 39 million Mexican pesos ($2 million at the time) improving the camp, but there have already been riots, escapes, and protests by migrants over delays in processing them.

Mexico has held growing numbers of migrants in camps since June 2019, when President Andrés Manuel López Obrador made a deal with the administration of U.S. President Donald Trump to keep them inside the country in return for a free trade agreement. U.S. border patrol stopped almost 9,000 Indians in 2018, the largest group hailing from outside Latin America.

Raja and Sanjiv’s teenage friend Manpreet did not survive. He became sick at the camp and was sent away, ending up at a hospital in Veracruz. It is unclear exactly what happened, but the 16-year-old died days later of a brain infection, in November 2019.

Manpreet’s body was cremated after a month but his ashes are still in Mexico. His family, who sold their house and borrowed money to send him to the U.S., cannot afford to collect them. His father, Nirmal, said he hasn’t even seen a picture of his son’s body.

“They didn’t send any snap or his post-mortem record or his pic, nothing,” he said.

A Surprise Return

Raja and Sanjiv were held for several weeks in Acayucan. They spent most of their time wandering around the yard, preparing for what they thought would be the final leg of their journey to the United States.

But on October 16, 2019, they were loaded onto six buses along with hundreds of their compatriots, without any explanation, and driven for several hours until they reached an airport.

“They didn't even tell us they were going to deport us.... They took people in all these buses, they took us to the airport, an international airport ... and there they deported us,” said Raja.

The Boeing 747 left Toluca International Airport carrying 310 men and one woman, all from India, guarded by Mexican officers. On the plane, many of the would-be migrants exchanged their stories. For some the prospect of returning was a relief after months on the move, eating badly and living out of their backpacks.

After a 36-hour flight, including a stopover in Spain, the migrants landed in New Delhi. Carrying little more than their passports, they found themselves back home. Many thought they would be imprisoned when they disembarked, but they were ultimately freed after being interviewed by authorities.

Raja is now about to lose his house. After mortgaging it to finance his trip, he can’t afford the monthly payments of up to $500. Sanjiv, who sold his house to pay the smugglers, is now struggling to raise the $20 a month it costs to rent the apartment where he lives with his mother.

Almost every day, they call the traffickers and beg for their money back. They were still waiting when they were interviewed.

“We had dreams too. Those dreams are broken. It happens sometimes,” said Sanjiv.