In the waning years of their father’s three-decade rule in Egypt, Gamal and Alaa Mubarak were masters of their world, hopping between investment forums, policy meetings, and luxury homes. The liberalizing economy under President Hosni Mubarak was booming, and the brothers had the connections to cash in.

Subsidy cuts were planned, state firms were lucratively privatized, and government-owned land could be had for cheap — if you knew the right people. The brothers accrued hundreds of millions of dollars’ worth of villas, luxury cars, and stakes in major Egyptian companies, eye-catching wealth in a country where a quarter of people lived on under $3.20 per day.

Their relatives and business partners prospered, too. Sweetheart deals padded the profits of companies owned by Mubarak in-laws and allies. And it seemed like it was only going to get better for the brothers: Gamal, who had spearheaded the economic reforms, was widely tipped to succeed his father as president.

That all collapsed in the space of just three weeks in 2011, when millions took to the streets across the Arab world, demanding accountability for a ruling class that had hoarded wealth and sent it abroad for decades. Mubarak resigned in February, and within 30 minutes Swiss authorities had frozen hundreds of millions of dollars’ of assets linked to him and his government.

Investigators launched a worldwide hunt for the Mubarak millions. Assets tied to other officials in Yemen, Syria, and Libya were also frozen in the following months and years. But a full accounting of the money stashed abroad has remained elusive, especially in the secretive jurisdictions they often favored.

Now, leaked data from Credit Suisse gives new insight into some of the wealth the Mubaraks and other elites held at the Zurich-based bank in the years before the Arab Spring, and after it started to rattle their hold on power.

The Suisse Secrets Investigation

Suisse Secrets is a collaborative journalism project based on leaked bank account data from Swiss banking giant Credit Suisse.

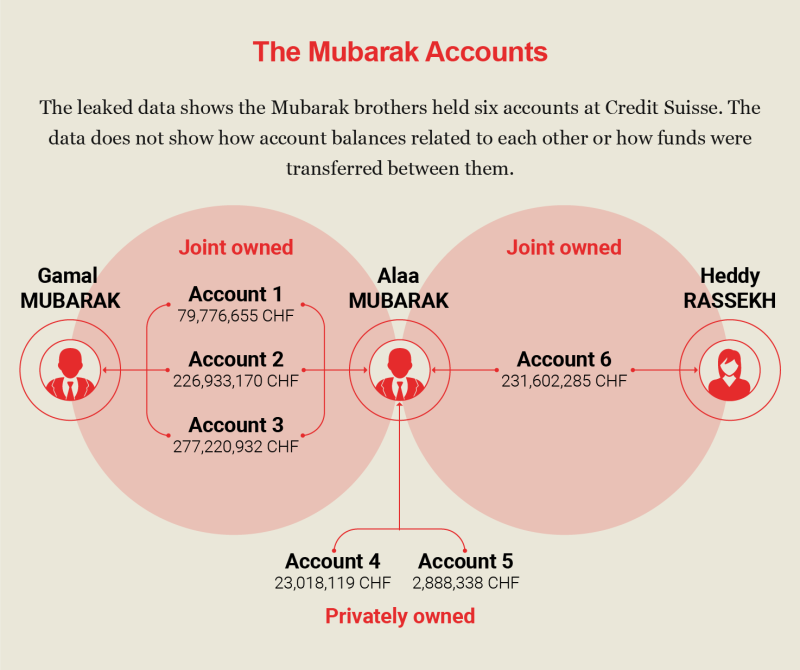

The data shows that the Mubarak brothers held six accounts at Credit Suisse. One of Alaa’s accounts was opened as early as 1987, when he was 27. Another joint account held by the two had a maximum balance worth 277 million Swiss francs ($197.5 million at the time) — amounts previously suggested by statements from Egyptian authorities, but never confirmed.

The brothers’ assets at the bank do appear to have been frozen after the Arab Spring, although Swiss authorities have not confirmed this explicitly. Through their lawyers, the Mubaraks said all of their assets “were fully declared and acquired from their professional business activities” and that they “originated from fully legitimate and lawful sources.” They said previous investigations into them were “politically motivated” and “driven by a campaign of flagrantly false allegations of corruption that was associated with the political events in Egypt of 2011.” After being “fully and intrusively investigated” for over ten years, authorities “unequivocally excluded any suspicious or illicit activity” on their accounts, they said.

The data also revealed previously unreported accounts held by the fathers of the Mubarak brothers’ wives, some holding millions of Swiss francs. More accounts were held by some of the family’s business partners, including some implicated in corruption trials both before and after the Arab Spring.

The leaked data contained more accounts from Egypt than any other Arab country. But many wealthy and powerful figures from around the region also show up in the data: presidents, royal families, ministers, spies, and business moguls with close government ties. The account holders came from over half a dozen countries hit by the Arab Spring protests, including Syria, Yemen, Libya, Algeria, Morocco, and Jordan. These accounts, which provide a glimpse into the wealth held abroad by Arab elites in the decade before the uprising, were collectively worth at least $1 billion held in just one Swiss bank.

The data also sheds light on the role Credit Suisse played for years in allowing some Arab elites to stash their wealth abroad, even as they and their governments were accused of compromising an entire region through corruption and nepotism — grievances at the heart of the Arab Spring protests.

Some customers held accounts despite years of scandals, as was the case with Hussein Salem, a close Mubarak associate whose name became synonymous with corruption and cronyism. Others, including spy chiefs, were implicated in human rights violations such as torture and U.S.-led extraordinary rendition.

Some experts who have followed illicit financial outflows from the region say that Swiss and other international banks were integral to moving the very funds Arab Spring protesters wanted to recover.

Waleed Nassar, a lawyer who worked on Egypt’s asset recovery efforts, said foreign banks regularly built personal relationships with wealthy customers in Egypt, who could then move money out of the country in a way that might have otherwise raised red flags. “You and I can’t go to a bank right now and get away with some of the most basic things that are atypical protocol-wise, but these guys can,” he said. “But for [the banks’] conduct, a lot of the money would have never have been able to be transferred outside of Egypt in the first place.”

Overseas Wealth: What We Knew

In a statement, Credit Suisse said it rejected “allegations and inferences about the bank’s purported business practices,” and said it was continually working “to strengthen its compliance and control framework.” The bank said that the accounts presented by the investigation were “predominantly historical” and “based on partial, selective information taken out of context, resulting in tendentious interpretations of the bank's business conduct.”

“While Credit Suisse cannot comment on potential client relationships, we can confirm that actions have been taken in line with applicable policies and regulatory requirements at the relevant times, and that related issues have already been addressed,” the bank said.

Historic Ties: Abdul Halim Khaddam

Over his years in government, former Syrian Vice President Abdul Halim Khaddam managed to accrue tens of millions of dollars’ worth of company shares, palatial mansions, and assets held in foreign bank accounts — a striking fortune for a lifelong public servant. Khaddam served in high-level government positions from 1970 to 2005, first as foreign minister and then vice president under Hafez Al-Assad. He rose to prominence in the 1980s while helping manage Syria’s involvement in neighboring Lebanon’s civil war, and its subsequent occupation of the country.

Seeking to foster pro-Damascus Lebanese politicians, Khaddam struck up a friendship with the wealthy businessman Rafik Hariri, backing his successful run for prime minister of Lebanon in 1992. Hariri was known to grease his relationships with money, and his friendship with Khaddam was no exception.

A former high-level Syrian official told OCCRP that Khaddam had “dominated Lebanon through Hariri,” who in turn paid him back with favors. He recalled meeting Khaddam in Damascus, where the vice president was “living a legendary life.” Khaddam had a reputation for a level of corruption that was so obvious it “does not need documents” to be proven, the former official said.

Further charges against Khaddam emerged after Hariri was assassinated during his second prime ministership in 2005, a murder widely blamed on the Damascus regime.

The following year, Khaddam defected from the Syrian government led by its current president, Bashar Al-Assad, and fled to Paris. In retaliation, Syrian officials began leaking details of his previous dealings.

In a briefing with journalists, officials said Khaddam had taken about $500 million from Hariri over two decades, some in the form of houses, yachts, and funds held in French, Lebanese, and Swiss bank accounts. Syrian media also reported that Khaddam had taken bribes in the 1980s to allow France and Germany to bury radioactive waste in the desert.

Details of Khaddam’s Credit Suisse account, which he held jointly with his wife and three sons, confirm the family indeed accumulated substantial wealth while Khaddam was in office. The account, opened in 1994, reached its highest balance worth nearly 90 million Swiss francs in September 2003 ($68 million at the time).

Khaddam died in 2020. His sons did not respond to phone calls or repeated requests for comment sent by email and text message.

The former vice president was just one among many Arab elites who used Switzerland to stockpile his wealth. For years, the country’s financial secrecy and relative stability made it a popular destination for legal and illicit funds.

“The perception that it was a safe haven for hiding wealth in a way which provided high levels of secrecy made it an attractive destination for many individuals,” Jackson Oldfield, a researcher at the Civil Forum for Asset Recovery advocacy group, told OCCRP. Switzerland and other European countries were also seen as “stable in the sense that this money’s not going to disappear because of currency fluctuations, because of unstable governments in the future,” he said.

In total, the Suisse Secrets data showed that five former or current heads of state and government from the Arab world held Credit Suisse accounts. It also included spy chiefs and others associated with intelligence agencies — the backbone of many Arab states — from Yemen, Jordan, Iraq, and Egypt. Some accounts were held by prominent business figures accused of acting as frontmen for Arab regimes.

Accounts of Arab Leaders

In Syria, these clients included Mohammad Makhlouf, the brother of former President Hafez Al-Assad’s wife, who acted as a front for his brother-in-law for years while leveraging his political ties into a commercial empire spanning tobacco, real estate, banking and oil.

The Egyptian tycoon Hussein Salem, a longtime Mubarak ally with links to the country’s intelligence agencies, was a Credit Suisse customer for over three decades. He held at least a dozen accounts with balances often running into the tens of millions, despite being publicly linked to corruption scandals for years before and after the Arab Spring.

Even Libya — sanctioned by the United Nations in 1992 to pressure Muammar Gaddafi to cooperate with investigations into the bombing of an airplane over Lockerbie, Scotland — provided numerous clients, including several individuals accused of plundering a public development fund over two decades.

Salem died in 2019 and Makhlouf died in 2020. OCCRP sent messages to Salem’s lawyer by email and to Makhlouf’s son, Rami, through his social media accounts, but did not receive a response. A lawyer for one of the Libyan businessmen said his “business activities have always been lawful and tax compliant.”

Networked Customers: Mubarak’s Egypt

From his senior position in Egypt’s ruling National Democratic Party, Gamal Mubarak oversaw many of his father’s economic reforms in the years before the Arab Spring. The liberalization was popular with investors, but did little to improve living conditions for many Egyptians. Poverty rates even rose, from around 17 to 25 percent, in the decade and a half until 2011.

At the same time, an elite network connected to the Mubaraks was profiting from the new business environment, buying state land and other assets for cheap and benefiting from state-backed loans. Many of the proceeds made their way into foreign bank accounts.

Corruption trials after the Arab Spring showed that, in addition to family ties and joint ownership in some of the country’s biggest companies, many of these elites were also connected by suspect dealings behind the scenes.

One of those to benefit was Mohamed Magdy Rassekh, whose daughter Heddy was married to Gamal’s brother Alaa. Throughout the 1990s, Rassekh accumulated numerous holdings, including in the gas sector. He also invested in real estate, serving as non-executive chairman of the Egyptian luxury property developer SODIC.

After the Arab Spring, a court found that Rassekh had conspired with a former housing minister to obtain plots of land outside Cairo at below-market rates. In 2012, Rassekh was sentenced to five years in prison, although last year he managed to strike a “reconciliation” deal with Egyptian authorities to pay over 1.3 billion Egyptian pounds — over $80 million at the time — along with the minister to have the charges removed. Rassekh did not reply to repeated requests for comment sent to his lawyer.

The Suisse Secrets data shows that Rassekh was a Credit Suisse customer for over half a decade before the Arab Spring. An account opened in 2005 was worth over 3 million Swiss francs ($2.5 million) the following year. It was closed in 2015, more than four years after his name first appeared on lists of figures whose assets were frozen after Egypt’s uprising.

Tracing assets held by Rassekh and other members of the Mubarak family shows how deeply family, business, and political ties were intertwined on the eve of the Arab Spring –– and how many of the system’s key figures held accounts at Credit Suisse.

Overlapping Interests

How did so many interconnected figures end up banking at the same institution? One former senior Credit Suisse executive told OCCRP that in emerging markets the bank often focused on recruiting staff from “good families” who “have access to wealthy families” and could provide referrals for other similarly positioned clients.

Often, the former executive said, introductions to so-called “politically exposed persons” would come at “a very senior level,” meaning the client would not always have to follow standard procedures, while those managing the accounts were “bureaucrats or functionaries” who “do not ask questions, have no knowledge of the region, and no banking knowledge.”

Credit Suisse said that it carried out appropriate due diligence and other control procedures.

“As a leading global financial institution, Credit Suisse is deeply aware of its responsibility to clients, and the financial system as a whole to ensure that the highest standards of conduct are upheld,” the bank said. “These media allegations appear to be a concerted effort to discredit the bank and the Swiss financial marketplace, which has undergone significant changes over the last several years.”

The Mubarak Accounts

Meet the New Boss

There is evidence that many Middle East elites sent money for safekeeping in Switzerland and elsewhere in Europe as protesters battered at the walls of their privilege at home.

Swiss authorities reported a surge in “suspicious transactions” — those potentially associated with bribery, money laundering, or other offenses — from Arab countries to over 600 million Swiss francs in 2011. They attributed the rise both to more stringent reporting requirements and Arab Spring unrest.

In September 2011, the Bank for International Settlements, a Switzerland-based financial institution owned by central banks, said international banks reported a surge in liabilities to Egyptian residents of over $6 billion, and to Libyan residents of over $2 billion, in the preceding three months, most likely reflecting “domestic funds being moved out of the two countries as a result of the elevated levels of political and economic uncertainty.”

The Suisse Secrets data does not show how many, if any, of these transactions involved Credit Suisse. But at least one elite customer was moving money abroad through the bank. Documents from a Spanish investigation showed that the family of Hussein Salem, the longtime Mubarak associate, transferred 3.5 million euros’ worth of money from Egypt to an account at Credit Suisse on January 24 and 26, 2011 — just as the protests were getting going in Egypt.

Panama Papers Connection

As the Arab Spring ground on, it became increasingly clear that the protesters’ demands to end corruption would be met only with piecemeal measures –– if at all. In Libya, Syria, and Yemen, uprisings collapsed into civil wars, quashing any hope for reform. Monarchies in Jordan, Morocco, and the Gulf states held strong while instituting cosmetic reforms.

Egypt’s democratic experiment ended abruptly in the summer of 2013, when a military officer named Abdel Fattah El-Sisi toppled the country’s first freely elected president, Mohammad Morsi. Optimism gave way to the realization that most of the Swiss assets frozen after the uprising would not be returned.

In Egypt, a series of “reconciliation” deals caused many corruption charges to be cleared. In 2017, Swiss authorities said they were ending their legal assistance program with Cairo and unfreezing related assets, although some 430 million Swiss francs under criminal investigation in Switzerland — the bulk of it apparently related to the Mubarak brothers — stayed frozen.

In November last year, an Egyptian court issued a final ruling canceling the Mubarak brothers’ asset freezes. Through their lawyer, the brothers said in December the Swiss federal prosecutor “gave notice to the parties of the imminent conclusion and closure of the case.”

Oldfield, of the Civil Forum for Asset Recovery, said that while the Arab Spring brought new attention to illicit financial flows between Europe and North Africa, “nothing has changed too substantially.”

“The underlying theme is still that it’s relatively easy to hide illicit wealth in Europe, and it’s relatively a welcoming place to do so,” he said. “This is not a problem which has ended. It’s still very much ongoing.”

Nassar, the lawyer who worked on asset recovery in Egypt, said that the efforts started to lose steam as the political will to find and return assets receded. Even under Morsi, he recalled that many officials questioned how successful the program would be.

“They were always skeptical of whether we could get any money back,” Nassar said. “In hindsight, I think they were prescient.”