Two are convicted drug traffickers. One has been charged with laundering money for a prostitution ring. Another sold U.S. equipment to the Syrian government. Three more are indicted for helping carry out a cryptocurrency scam that stole billions of dollars from investors.

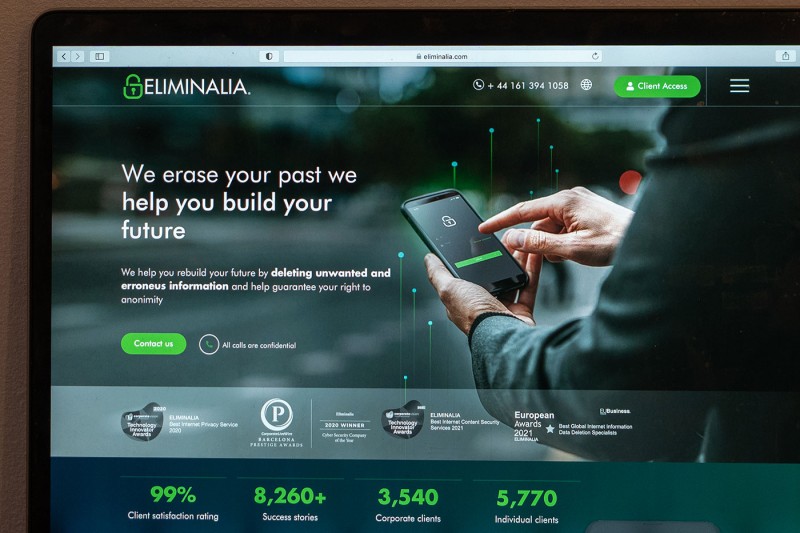

These are some of the over 1,400 clients — including dozens who have been convicted or suspected of crimes — who have hired Eliminalia, a reputation management company that promises to “erase your past.”

Based in Barcelona, Eliminalia has been laundering reputations for a decade. From a wood-paneled coworking space on the historic shopping street of Portal de l’Àngel, which it shares with two dozen other tenants, the company has emerged as a significant player in the global disinformation-for-hire industry.

Officially, the man behind Eliminalia is Diego “Didac” Giménez Sánchez, a 30-year-old Spanish entrepreneur now thought to be living in Georgia. Sánchez claims to control a sprawling network of companies, including a Ukrainian surrogacy business that is under investigation for trafficking in babies.

But he appears to have built this network with a man named Jose Maria Hill Prados, who was convicted of sexually abusing him as a minor. Although Hill Prados’ name does not appear on Eliminalia’s records, Spanish investigators suspect he may control the reputation manager, too.

Thousands of leaked files — obtained by French non-profit Forbidden Stories and shared with OCCRP and dozens of partners — allowed reporters to map Eliminalia’s extensive web of digital influence. Building on previous reporting, the documents give unprecedented insight into the array of underhanded tactics the company uses to stifle criticism of its clients.

The records show Eliminalia — which changed its name to iData Protection S.L. in late December — used copyright and privacy laws to intimidate journalists, manipulated search engines to hide information, and churned out fake news. In some countries, the company has even opened new business ventures with its own criminal clients.

Experts say Eliminalia is part of a growing disinformation industry that helps bad actors, from criminals to kleptocrats, to hide their murky pasts.

“This whole mechanism, this commission of money and reputation laundering, this everyday kleptocracy, depends today on transnational professional intermediaries,” said Tena Prelec, a research fellow at Oxford University who studies transnational kleptocracy.

“You have a whole series of professional service industries, such as public relations agents, lobbyists, lawyers … who basically help in this retasking of unsavory individuals and companies and governments as internationally respected businesspeople and philanthropic cosmopolitans.”

Eliminalia’s lawyers declined to respond to questions for this project, arguing that many of them concerned business secrets about the company’s clients. They accused journalists of bias.

“The orientation and content of the vast majority of the questions demonstrate a partial and dishonourable approach,” they wrote.

What Is the Eliminalia Leak?

Criminal Services

Sánchez — who presents himself as a self-made entrepreneur — was just 20 when he founded his first reputation management company in Spain. Over the following years he opened several other businesses, eventually moving his base to Ukraine, where he hired people to write made-up reviews and fake legal notices to journalists.

Among Sánchez's many ventures was a surrogacy business named Subrogalia, which connected Spanish parents with Ukrainian women who could carry their babies. Although he is the public face of the company, documents obtained by OCCRP show its Ukrainian business was in fact owned by Hill Prados — who was imprisoned in Spain for sexually abusing Sánchez as a minor.

Two Spanish law enforcement officials in charge of cyberthreats, who asked not to be named because they were not authorized to speak to the media, told OCCRP they suspected Hill Prados was the beneficiary of Eliminalia. They did not elaborate on their evidence, however, and OCCRP could not independently verify the claim.

Eliminalia is part of a network of at least 54 companies in nine jurisdictions linked to Hill Prados and Sánchez in the past decade. Neither of them agreed to comment on this story.

Sánchez has said previously that he created Eliminalia because of a desire to erase stories about his own past as a victim of Hill Prados.

“It tortured me so much to find mention of what had happened in my childhood on the Internet,” he wrote in his self-published autobiography, The Secret of Success. “I set about studying how to [scrub references] and in a few weeks had succeeded in deleting most of what had been written. Thus I saw there was a market for this and created Eliminalia.”

Some of Eliminalia’s business comes from ordinary people seeking to erase malicious material posted about them online, as part of a growing push to strengthen “right to be forgotten” laws. But reporters found many of the clients on the reputation manager’s books were criminals, who enlisted Eliminalia to manipulate those same laws in their favor.

The leaked internal documents suggest that Eliminalia has provided services to over 1,400 clients, including hundreds of people who have been accused or convicted of crimes, from drug trafficking and sexual assault to fraud and money laundering.

Italian company Area S.p.A. paid Eliminalia at least 100,000 euros to remove 72 media reports that it had been fined in the U.S. for illegally providing equipment to Syria’s sanctioned government. Not long after Area and Eliminalia signed the contract, articles on everything from K-Pop to blockchain mentioning the company’s name started flooding the Internet, drowning out legitimate news reports on Area’s dealings with Syria. Area told OCCRP it hired Eliminalia to remove content through legal means only, because it was often incorrect and unfairly presumed the company's guilt.

Malchas Tetruashvili, a money launderer for Russian-Georgian mafia boss Tariel Oniani, paid Eliminalia 30,000 euros to get rid of 79 links to unfavorable content about him, after a Spanish court sentenced him to five months in prison. Tetruashvili did not respond to a request for comment.

Antonio Herrero Lázaro paid Eliminalia a total of 15,600 euros to target 18 articles about his involvement in a prostitution ring in Spain, for which he was convicted in 2014. Though the verdict was overturned, he is currently under indictment for aggravated tax fraud. Herrero did not respond to a request for comment.

José Mestre Fernandez, who was sentenced for heading a cocaine trafficking network in Barcelona,was also among Eliminalia’s clientele. Mestre paid just over 30,000 euros to Eliminalia between 2016 and 2020. He did not respond to requests for comment.

Higini Cierco and Ramon Cierco, former co-owners of Banca Privada d 'Andorra, hired Eliminalia to delete articles about investigations into the bank’s money laundering for a powerful criminal gang. Internal records show that the Cierco brothers paid the company almost 245,000 euros between 2016 and 2020. An attorney for the Cierco family said they would not have employed a company that uses unethical tactics.

Eliminalia was also engaged to represent prominent resellers of OneCoin, a fraudulent cryptocurrency scheme that stole billions of dollars from investors. Three brothers — Aron, Christian, and Stephan Steinkeller — are accused of making millions of euros from the scheme, and are facing charges in Italy. A company paid Eliminalia 38,000 euros on their behalf in 2021. The Steinkeller brothers did not respond to a request for comment.

Prelec, from Oxford University, said it has become “absolutely normalized” for service providers such as lawyers and public relations firms to launder the reputations of problematic clients. Flying under the radar of search results could change the outcome of a customer due diligence check at a bank, or other regulated service provider.

“The idea that accepting shadowy money into our economies, accepting that people can use their wealth … to manage their reputation aggressively, to the detriment of the truth-exposers – that is not okay,” she said.

Eliminalia’s Top Customers

These companies and individuals were some of the highest paying clients in the data leak obtained by Forbidden Stories.

Eliminalia has also partnered with its own questionable clients to expand their business.

One client, Italian law firm Studium Srl, went on to found a reputation management company called Digitallex, which then handled part of Eliminalia’s Italian business. In 2021, authorities launched an investigation into Digitallex’s shareholders for money laundering, fraudulent bankruptcy, and tax evasion. The company did not respond to questions.

”[A]ccepting that people can use their wealth ... to manage their reputation aggressively, to the detriment of the truth-exposers — that is not okay.”

Tena Prelec

Research fellow, Oxford University

Another Italian partner, Enea Angelo Trevisan, hired Eliminalia after being convicted of bankruptcy fraud in 2015. He appears to have gone into business with the reputation managers two years later, founding an Italian company called Eliminalia Holding Sa, and several others, to manage Eliminalia’s business in Switzerland and Italy.

In 2018, Trevisan split from Eliminalia and rebranded one of these companies, Eliminalia Italia Srl, as Ealixir. Now selling its own services to remove online content out of the U.S., Ealixir has plans to go public on the Nasdaq Stock Market, and recently expanded into Latin America and the Caribbean.

Trevisan did not respond to a request for comment.

‘A Mechanism of Harassment’

Mexican journalist Daniel Sánchez had just published an investigation into a state governor’s suspicious contracts with a Mexican video surveillance company Interconecta in January 2018 when the phone calls began.

At first, he said, the callers were fellow journalists who urged him to take down the story. Soon enough, he received a call from a man named Humberto Herrera Rincón Gallardo saying he worked for Eliminalia, who also pressed him to withdraw the article.

Gallardo’s tone was friendly, explaining that the investigation was hurting Interconecta’s bottom line. But after his call, things started to escalate.

A page that looked strikingly similar to the publication Daniel Sánchez works for, Página66, popped up on Facebook and began publishing fake articles under his name. Then a mosaic of photos started circulating on social media showing him alongside other journalists, activists and politicians, accusing them of being “enemies of the government."

Two local journalists he knew turned up and, he said, offered him bribes to take down the story. He said he also fell out with a close personal friend who also tried to pressure him.

Daniel Sánchez said he is convinced Eliminalia was behind the campaign against him. “They include a whole mechanism of harassment so that they achieve their objectives,” he told OCCRP.

Leaked Eliminalia documents show that Gallardo was in fact representing Eliminalia’s client, Grupo Altavista, the parent company of Interconecta. In April 2019, the group hired Eliminalia to target 13 links that mentioned their company, including Sánchez’s investigation published by Página66, for less than 13,000 euros.

Eliminalia’s owner, Diego Sánchez, said in a media interview that his company had entered Mexico “because we found that the countries where there is more corruption and political problems are where there are more business opportunities.”

Daniel Sánchez said the harassment left him fearing for his life. Mexico is one of the most dangerous countries in the world for journalists, with the government reporting that at least 55 have been assassinated between 2018 and 2022.

Then, in 2020, Página66 itself was taken down by host Digital Ocean for a week after someone filed a copyright infringement notice against the news site, according to Daniel Sánchez. An online record of the request shows it was filed by Gallardo, who gave an address in the U.K.

Gallardo denied working for Eliminalia, harassing Sánchez, or filing the notice. “If my name appears in any [complaints], it has been misused, without my consent and without my knowledge,” he said.

An investigation by Articulo19, the Central American branch of the press freedom group Article19, determined that multiple journalists have been targeted with similar tactics. Priscilla Ruiz, legal coordinator of the group’s digital rights program, said it had identified at least one other case also linked to Eliminalia.

Ruiz said Articulo19 had spoken to Mexican law enforcement about challenging the fake copyright infringement notices from digital platforms in court, but the limitations of the law made it hard to put together a case.

“In Mexico it is difficult to argue that false notifications of copyright infringement, issued by a shell company that has no record of its existence, are proof of fraud, as in the Eliminalia case,” she said.

Erasing the Past

The notices filed against Página66 show how Eliminalia has exploited laws to intimidate its clients’ critics. Reporters found the company has made a business model out of weaponizing U.S. and European Union privacy and copyright regulations.

OCCRP itself has been the target of these tactics. In 2019, editors received an email claiming that a long-standing investigation, which showed Swiss bank CBH had moved $277 million in suspicious funds via shell companies owned by Russian billionaire Alexey Krapivin, had violated the EU’s data protection regulations.

The message came from [email protected], one of multiple official-sounding domains Eliminalia has used to send legal threats to media outlets. Reputation managers have increasingly deployed messages like these in recent years to push publishers to delete content or simply waste resources addressing them.

Documents show that CBH had hired Eliminalia’s Italian partner ReputationUp to target online content that linked it to offshores and money laundering. According to the data, CBH paid 229,000 euros to Eliminalia for the work, making it one of the highest paying clients in the data set.

Many of the emails Eliminalia sent alleging privacy violations were signed by “Raul Soto,” an apparent pseudonym used by an Eliminalia employee posing as an official of the European Commission in Brussels. An analysis of one of these emails’ source code by Qurium, a nonprofit specializing in digital forensics, found the messages were sent from an IP address in Ukraine, where Eliminalia operated until the Russian invasion last year.

A lawyer for CBH confirmed the bank had contracted ReputationUp, but said it was unaware of its relationship to Eliminalia. “CBH has never tolerated that any illegal actions be taken on its behalf by anyone,” he said in a statement.

The Dangers of Disinformation

A few months later, Eliminalia used another tactic to target an OCCRP article about CBH client Derwick Associates, an offshore firm that received $5 billion worth of energy contracts from the Venezuelan government without competition. The story mentioned the former CBH manager who handled Venezuelan clients for the bank, Charles-Henry de Beaumont — another Eliminalia customer.

The company cloned OCCRP’s investigation, “Plunging Venezuela Into the Dark,” onto a fake news website Noticias-Politica.com, backdated it, and initiated a complaint under the Digital Millennium Copyright Act, a U.S. law that requires online service providers to react immediately to complaints to avoid liability for copyright violations.

The goal of such tactics is to get Google and other search engines to remove authentic articles from search results. This has become an increasingly common form of disinformation in recent years, said Katherine Trendacosta, associate director of policy and activism at the Electronic Frontier Foundation.

“[Of] the sort of tactics that I have seen, I will state that copyright is one of the easiest. It's very easily abused,” she said.

A spokesperson for Google said it fights fraudulent takedown attempts through automated and human review processes, and allows sites to file “counter notifications” if content has been removed in error.

Noticias-Politica.com is just one of some 600 fake news domains set up by Eliminalia, according to an analysis by Qurium. They are designed to appear like real sites, but in reality are populated with content stolen from legitimate outlets like The Daily Mail and Le Parisien, along with backdated stories used for erroneous copyright claims.

Qurium found a lot of the sites mentioned a company called Communication Media Group Ltd. in their fine print, along with an address in the Caribbean island nation of Saint Kitts and Nevis. The websites also used clusters of IP addresses, at least two of which were allocated to Maidan Holdings LLC, until recently the parent of Eliminalia Ukraine.

These sites were used for tactics such as cloning the target story and removing their client’s name, and generating positive or neutral fake stories mentioning their client in the hope search engines will index them above the legitimate ones. An Eliminalia contract viewed by OCCRP spells out the goals to the customer: push down the “unwanted information” to the third page of the search engine “so that it is more difficult to find.”

Eliminalia also manipulated Google’s algorithm through “backlinking” — creating as many links as possible between websites — so they rise through the rankings. In one instance, operators for the reputation manager posted 7,000 links on an unsecured black student union forum at a community college in order to backlink 2 million of Eliminalia’s fake news articles.

Eliminalia is now advertising more aggressive online tactics. In an interview late last year from Georgia, where Sánchez had set up new companies, he told a TV interviewer that he was operating "an army of hackers” to target Russian online disinformation.

But when a reporter visited the new office he recently established in a residential neighborhood of the capital, Tbilisi, they found no sign anyone was working there.

Eliminalia in Spain, meanwhile, rebranded in January. Sanchez’s name still appears in the Spanish registry as the company’s sole owner, but the management was changed in November to exclude him.

At the co-working space in Portal del Àngel where Eliminalia was based, a new sign now reads “IDATA PROTECTION.”

“We were Eliminalia, but now we are IDATA,” said an employee who answered the door.