The world got a little smaller on July 17, 2016.

That evening, television news reports in Peru and in Serbia were covering the very same story: A global drug trafficker who had switched among 40 identities to escape justice for years had finally been caught.

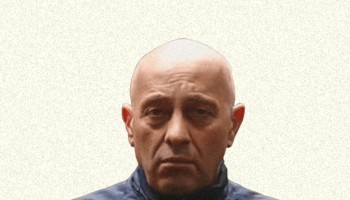

The footage of the arrest in northern Peru was dramatic. Zoran Mihajlović Jaksić, the “right hand” of the world-spanning Group America gang, tried to hide his face from TV and police cameras. Four local policemen had to hold him to keep him from running. It was the grand finale of a year-long police operation.

Using thousands of pages of court files and interviews with prosecutors, policemen, and intelligence agents, OCCRP and its Prague-based member center Investigace.cz were able to reconstruct Jaksić’s role in the organized crime group, his ties to Peruvian drug families, and the police work that finally brought him down.

When he first came into view, those Peruvian investigators weren’t even looking for him.

Hunting for Swallows

In early 2016, Peruvian police were already deep into a long-running operation targeting a group of home-grown drug traffickers known as Golondrinas (“Swallows”).

The name of the organization was derived from its daring use of small planes to transport cocaine to Brazil for onward shipment. It was thought to be a regional operation run by a few local families.

“We had no idea such a big player was involved,” a police official told OCCRP. “We don’t have players like him in Peru. He is the Champions League.

Group America’s foothold in the country changed the very structure of its drug business. Until Group America, Peru’s cocaine trade was dominated by small families, not international businesses or cartels.

“Peruvian criminals just produce cocaine, so they are the ones who earn the least in the whole chain,’’ said the investigator, speaking on condition of anonymity for his own safety. “Peruvians never established international networks and contacts.That’s why they need people like Jaksić, who make it possible for Peruvian cocaine to be sold in the world.”

A Big Man in Lima

The investigation into the Golondrinas focused on three families: Rojas Vilcatoma, Medina Gavilán, and Soto Cordova.

The families bought cocaine from coca farmers, packed it in cheap bags and simply drove it to Lima for wholesalers to take it out of the country. In 2016, their joint sales were coordinated from Lima’s Lurigancho Prison by Jorge “Jota” Medina Gavilán, who was serving time on a drug charge but operating through his brother, Fernando.

Jota didn’t know that the police were listening in to his family calls. During one of those calls, they heard him tell Fernando, “There is a stranger and he wants to buy. You will recognize him by his height. He is very tall.”

Jaksić’s introduction to the three families had come through Héctor Soto Cordova, a Peruvian drug trafficker the Serbian had met while serving a five-year prison sentence following a 1998 drug trafficking arrest.

Investigators later overheard other two drug dealers talking about Jaksić, then had no problem picking him out of the crowd in a Starbucks coffee shop in February 2016. At more than two meters tall, bald and pasty white, he didn’t blend in with Peruvians.

His daily routine also made for easy surveillance: From his room at the Lima’s Caminos del Inca apartment hotel he habitually went to the gym, then to a restaurant and back to the hotel.

Understanding his plans and listening in on his calls was much harder.

Jaksić used public phones and encrypted messaging systems on his mobile phone so the police couldn’t intercept his calls.

Nor were they exactly sure who the big man really was. Jaksić would shift among 40 different identities, often using false passports from Serbia and Bosnia and Herzegovina.

But they knew from their other wiretaps that he wanted to buy three tons of cocaine.

And they knew that Jaksić was linked to Group America leader Mileta Miljanić, a known drug runner living in New York who had sent his own son, Petar Miljanić, and an associate, Nikola Stevanović, to Lima to learn the drug trade from Jaksić. Police assigned the students nicknames: Petar Miljanić was “Mudo,” or mute, because he seldom spoke. Stevanović was the “Boxer.”

Jaksić had been buying cocaine in Peru since at least November 2015, and had already shipped a ton through the Port of Antwerp by the time his protégés arrived in June 2016.

But only after an underworld source told police the big man had previously spent time in a Peruvian prison were they able to determine his true identity.

“It was not that difficult to ask around prisons [about a] two-meter tall, muscular, bald white guy,’’ the investigator said. “People remembered him.”

On learning Jaksić’s name, they discovered from Interpol that the Serbian native was wanted in Argentina, Germany and Greece.

Closing In

The Golondrinas investigation, which had been expanded into a series of major drug busts and arrests that police called a “mega operation,” was scheduled to end with a flourish in April 2016. Authorities in Peru invited representatives of international drug enforcement and intelligence bodies to gather in Lima for Jaksić’s arrest.

But Jaksić disappeared just as the police were about to pounce.

Investigators came up with just one lead: Jaksić “went up north,” they learned from wiretapped conversations. Only later did they realize they already had the crucial information that would lead them to him.

Just days before Jaksić ran, a police wiretap had captured a conversation in Serbian. Lacking a translator in Peru, investigators sent the recording to the United States.

Though slow in coming, the translation revealed that Petar Miljanić knew the police were after them and had called Jaksić to say they had to disappear.

Investigators eventually found Stevanović in a Lima hotel and learned he was about to fly “up north,” to Tumbes, a small city close to the Ecuadorian border. They followed him and instructed local police to detain any tall, bald white men they might see.

At the Tumbes airport, Stevanović asked a cab driver to take him to Ecuador.

That’s normally a 30-minute trip. Police waited at the border, but after three hours the cab still had not arrived.

Investigators had lost Stevanović, but Jaksić’s luck was about to run out.

That night a man matching Jaksić’s description was detained trying to cross the border using a false passport. His fingerprints matched Jaksić’s file from 1998. The big man was flown back to Lima to face drug trafficking charges.

In February 2019, Peruvian prison authorities announced that Jaksić was planning an escape from Lima’s Miguel Castro Castro prison, where he was being held pending trial.

“The inmate had intention to escape through medical attention, so to prevent this plan, we authorized his transfer,” said Rubén Ramón Ramos, regional director of the National Prison Institut of Peru.

A Prison Institut representative said Jaksić is now being held in Ancón I, a maximum security prison better known as Piedras Gordas, north of Lima. The overcrowded prison was recently hit with a coronavirus outbreak, with inmates allegedly falling ill and being given no protective equipment. Prominent prisoners held there include a former regional governor sentenced for corruption, and lawyers implicated in Brazil’s infamous Odebrecht scandal.

In April, 2019, the big man was sentenced to 25 years in prison. Authorities in Greece have requested his extradition there if he is ever released.