On a cold winter day in Gdansk, Zoran Jakšić scrambled to fix a problem not of his making.

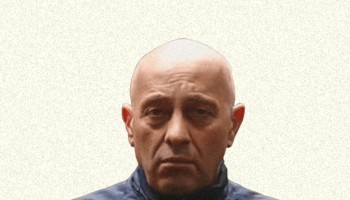

The second-in-command of Group America, a major international narcotics trafficking organization, was in Poland to prepare for a drug delivery.

But at 12:42 p.m. on January 28, 2009, Jakšić received a troubling call from an associate called Milan who was in contact with Dragan Vujović, a crewman on the cargo ship MV Senator. The ship was scheduled to reach Europe in a few days with US$8.2 million in cocaine from South America smuggled aboard.

Now there was a huge problem: The ship had been sold mid-voyage. The new owners were replacing the entire crew.

Vujović was calling from the docks in Durban, South Africa, where Group America’s 230 kilograms of cocaine was now endangered. Group America had no one who could retrieve the shipment in the two or three days the Senator would be in port.

Jakšić is well-versed in the logistical chaos of international drug smuggling, but this crisis presented unique challenges, starting with the fact that he had no idea where Durban was.

The ability of Jakšić and his associates, working long-distance from three continents, to create a new criminal network to rescue their drugs — and to do it within hours — demonstrates the audacity, reach, and skill of Group America.

They almost pulled it off.

Low-key Operations

In a world where Pablo Escobar is a household name and the brand of the Sinaloa Cartel rivals that of Coca-Cola, Group America remains an enigma. Though the group feeds a sizable share of Europe’s cocaine habit, it has succeeded precisely because it flies largely below the radar.

OCCRP and two of its member centers, KRIK in Belgrade and investigate.cz in Prague, have tracked the organized criminal group for years, collecting thousands of pages of confidential police reports, interviewing law enforcement officials, and even visiting Jakšić himself in a Peruvian prison.

What emerged is a picture of a well-disciplined, nimble, and creative network with a unique business model. Unlike the cartels that control the cocaine supply chain all the way from coca fields to the street, Group America specializes in being the middleman.

“The group's policy has been to propose/offer itself as an efficient and reliable ‘service agency’ in the context of international drug trafficking, purchasing drugs directly from South American producers, transporting them and delivering them only to wholesalers operating in Europe,” reads a 2010 report by Italian investigators obtained by OCCRP.

When it’s threatened, the gang just melts away.

“The group is very economically strong, with a clear hierarchical structure and able to create an operational base in any city and then disappear or quickly disperse in cases of emergencies,” the Italian report reads.

Group America’s leader is Mileta Miljanić, an unassuming 60-year-old living in Queens, New York. He and Jakšić oversee a criminal enterprise that, in addition to cocaine, also profits from identity theft, counterfeiting and murder.

The gang’s true reach was laid bare in 2009, when Italian police stumbled onto one of the world’s biggest drug trafficking operations by following an Italian organized crime figure in Milan to a meeting with Group America wholesalers.

Over several months, the Italian cops shadowed Jakšić, Miljanić, and their operatives, eavesdropping on their conversations through telephone wiretaps and recording them with microphones and cameras hidden in cars and hotel rooms. That surveillance is the best-known record of the organization’s inner workings.

In written reports obtained by OCCRP, Italian police and prosecutors call Group America “a leading player in the cocaine trade between South America and Europe, managing to only in a few years create a monopoly over almost the entire maritime routes of drugs supplying the European market.”

No law enforcement agency can say with certainty how big the organization really is, but some insight comes through its failures. Police in more than a dozen countries have seized more than five metric tons of cocaine from Group America’s shipments over the past 20 years.

Evidence gathered in 2016 by police wiretaps in Lima, Peru, also shows the size of the gang’s business and profits. According to recordings, Jakšić told local producers that he needed more cocaine.

“I need two, three tons to buy,’’ Jakšić said. “I have another quota. In one month I have another quota for two, three tons.”

These amounts suggest the staggering sums Group America could make over a short period. At the time, the gang could buy a ton of cocaine in Peru for $1.7 million and sell it to European dealers for as much as $40 million.

Criminally Creative

Seizures of Group America’s cocaine across Europe and South America demonstrate the group’s growth in sophistication and inventiveness:

In 1998, Jakšić was in Peru, trying to ship cocaine in spray cans to the United States. This was not unusual for Group America, which likes to test new smuggling routes and methods before sending large loads. His arrest for smuggling 1.2 kilograms to Miami resulted in a two-year sentence.

In 2000, Group America sent 164 kilograms of cocaine hidden in ceramic cups from South America to a front company in Banja Luka, Bosnia and Herzegovina. Customs officials found the drugs during a warehouse inspection.

In 2001, 20 kilograms of Group America cocaine secreted in deodorant containers were discovered by the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration in Panama.

In 2004, 60 kilograms of cocaine was found hidden in the glue of asphalt tiles shipped from Venezuela to Novi Sad, Serbia, by two Group America-controlled companies. The hidden drugs were spotted when the tiles passed through Italy.

In 2008, police in Argentina disrupted the group’s plan to send liquified cocaine to Europe in wine bottles imported by an Italian front company. Jakšić had organized Argentinian, Peruvian, and Ecuadorian associates to make the scheme possible. This willingness to transcend nationality and ethnicity in getting the work done is one of Group America’s hallmarks.

While Group America has shown a flair for concealing shipments in unusual ways, it still relies on a tried-and-true technique: entrusting plastic-wrapped packets to sailors who work trans-Atlantic routes.

“In terms of narcotics transfers, [Group America] operates using Montenegrin sailors on commercial or cruise ships docking at South American ports and then arriving in Europe,” the Italian police wrote.

Even those simple plans can go wrong, as Jakšić discovered in February 2009.

He was in Gdansk to supervise the arrival of 32 kilograms of cocaine from Argentina hidden aboard the cargo ship Samutra.

Meanwhile, having already disrupted Jakšić’s operation in Buenos Aires, Argentinian police snared 174 kilograms in a raid in the city’s Recoleta neighborhood.

The drugs were to be sent to Venice aboard the cruise ship MSC Armonia, which sailed with only 10 kilograms in the care of a Montenegrin sailor. Even that smaller shipment was snagged by police.

Crisis in Durban

The Italian investigators were clearly impressed by Group America’s scramble to retrieve the shipment stranded in South Africa.

"This event indicates a perfect and compounded organizational structure," they wrote. “Miljanić and Jakšić managed to quickly contact people of trust and find a way to receive a specific amount of cocaine in Africa.”

They did it from a less-than-ideal starting point.

“Where is that, Durban? In which country... where is it? In South Africa? Or... where?“ Italian police heard Jakšić ask Milan on that January day in 2009.

The two men discussed various options, using the gang’s arcane language of code words and slang that relies heavily on crude sexual references. Operatives and drugs may be referred to as lady friends, women, girlfriends, or whores. Kilogram packages of cocaine are called “contracts.”

In one SMS conversation, for example, Jakšić tells associate Zlatko Kosović that, “I am preparing lady friends, here in P[oland].”

"Perfect, don’t worry about anything," Kosović writes back. “You know that when sex is about, discretion is guaranteed — at least from our side. Bye!”

Complicating the Durban issue was ownership of the drugs. Only 80 of the “contracts” actually belonged to Group America. The bulk, 150 kilograms, was being carried for hire, destined for another organization that police never identified. Jakšić didn’t trust the other group and didn’t want it involved, even if that organization could get all of the packets out of Africa.

The smuggling method had been simple: Sailors carried backpacks, suitcases, and duffel bags loaded with drugs onto the ship in Buenos Aires and stacked them in plain sight in the cabin of Branimir Orač, a Croatian kitchen worker.

"There were so many backpacks in his cabin that it looked like he was getting ready to climb Kilimanjaro," Johan Booysen, head of the South African Police Service’s organized crime unit, later told a local news outlet.

Orač told authorities the crew had been instructed to fling the bags into the Strait of Gibraltar for pickup.

Cashiered in Durban, the sailors now had no way to offload the bags without attracting attention; no clear path through the port; and no safe storage place like the short-rental garages or apartments the gang commonly uses.

A few hours after receiving the bad news, Jakšić called Miljanić in New York. The two agreed that Jakšić should consult Goran “Gypsy” Nesic, a Brazil-based Serbian narco boss who is close to Group America.

Nesic recommended a contact in the Nigerian underworld. Though Miljanić worried the Nigerian might not be trustworthy, Jakšić assured him that Nesic, nicknamed Ciga, had vouched for the man.

"Ciga will not fuck me... that [Nigerian] guy is his man," Jakšić said. “Ciga guarantees everything!”

Unlike gangs that tend to use a small network of trusted insiders, Group America is known for its willingness to reach out and establish new networks, particularly when dealing with an urgent problem.

In a 2017 interview in a Peruvian prison, Jakšić bragged about the reach of his contacts, referring to a fellow inmate.

“When I need information on the drug scene in Israel, I call Tibo and ask, ‘Hey, Tibo, who is doing wholesale drugs in Israel?’” he said. “You know, just to get the business insight."

At 7:36 p.m. on January 29, just under 29 hours after hearing about the diversion of the Senator, Jakšić and the Nigerian spoke on the telephone to make arrangements for a pickup at the docks.

One hour later, Jakšić learned that South African police had raided the Senator. According to a police transcript, he lamented that “everything he touches goes wrong.”

In fact, it had all gone wrong weeks earlier.

According to the Croatian newspaper Vecernji List, South African police who interviewed the crew flashed a surveillance photo of Orač, the kitchen worker with the backpacks in his cabin, meeting with drug traffickers in Buenos Aires. Orač confessed on the spot. He was the only Group America operative charged in South Africa, where he received a seven-year prison sentence.

Grudging Respect

In their assessment of Group America, the Italian officials described Miljanić, the organization’s head, as its “promoter and financier.”

“The leadership of Miljanić... was also essentially strategic, because the execution of all the operational phases of drug trafficking was in fact directed by Jakšić,” they wrote.

Though nearly identical in age, background, and experience, the personalities of the two gang leaders are at once conflicting and complementary.

Both are tough and comfortable with physical violence, but where Jakšić is hot-headed, Miljanić is calm and methodical. Group America’s low-key approach is largely attributable to his style.

While listening in on the gang’s operations in Milan, Italian police captured a telling conversation: Miljanić, who had recently arrived in the city, urged his tempestuous associate to keep calm and never take chances.

“Everything should be relaxed, simple and normal!” Miljanić advised. During business deals, “You should not shout… Please, don’t shout and scare others.”

But the low-key Miljanić embraces violence when needed.

Multiple murders attributed to the gang in Serbia in the 1990s include the torture and chainsaw dismemberment of a rival mobster.

Another member, known as Srećko (“Lucky” in English), told police about the incident and other Group America killings. Years later, Italian police listened in as Miljanić and Jakšić calmly discussed the need to kill Srećko, who was shot dead in Belgrade.

Another suspected victim of the group, a Serbian criminal murdered in Hungary, was beheaded in 2002. His body was burned, but a police report notes that the “head was found 11 days after the body was found, which leads to the conclusion that it was kept in the fridge.”

Police in Peru have also connected Group America to the murder of a Serbian criminal there in 2014.

While many of Group America’s alleged victims have been other criminals, the gang was also accused of political assassinations in Serbia, including the murder of a Belgrade police general in 2002.

Success through Moderation

In June 2019, U.S. drug agents made a record seizure of nearly 20 tons of cocaine valued at more than $1 billion from the MSC Gayane, a container ship that docked in Philadelphia while sailing from South America to Europe. Only a few low-level crew members have been charged.

It’s unlikely that Group America had anything to do with the Gayane — it’s not their style.

Though the group moves tens of tons of cocaine each year to Europe, it seldom sends more than 100 kilograms per shipment. This low-key strategy has served the gang well.

Smaller shipments are much less likely to attract attention, and if the operation is blown, the financial damage is limited.

Smaller loads can also be entrusted to an endless supply of low-level operatives, allowing gang leaders to minimize their own exposure. In most instances where Group America shipments have been seized, the only people to see the inside of a cell are disposable couriers, like Orač, the sailor in Durban.

Overworked police and prosecutors are much less likely to devote limited resources to long-term investigations that might net senior traffickers when the haul looks relatively small.

As seen time and again in the history of Group America, courts in most countries tend to levy sentences in proportion to the size of the immediate seizure, not the cumulative weight moved by a gang.

Yet Jakšić and Miljanić have both done serious prison time over the years.

Jakšić is now serving a 25-year sentence in Peru following a 2016 trafficking arrest. Though authorities say he still conducts gang business from prison, the 60-year-old may die behind bars. If he ever leaves the lockup, he’ll be extradited to Greece, where he is wanted on a 2007 drug trafficking charge.

Jakšić also faces trial in Italy in 2021 for his alleged involvement in the MSC Armonia operation.

Over the years, Miljanić has done time in the U.S., Greece, and Italy, where he’s still subject to arrest for absconding from a prison early-release program in 2014. But for now he’s now free to live openly in the United States and to travel, as long as he avoids Italy.