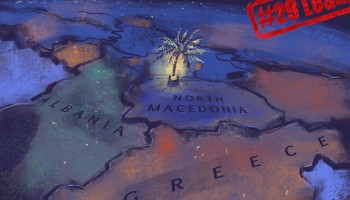

Hundreds of companies and banks owned by people across the world bear the impressive-sounding address of One Enterprise Way, Business Enterprise Zone, Banjul.

When it was created six years ago, the zone was touted as a groundbreaking venture to create a thriving high-tech offshore investment destination in the tiny West African country of Gambia, and a hefty revenue stream for the country’s people.

But what those doing business with the companies headquartered at One Enterprise Way may not know — in fact, were deliberately kept from knowing — is that the Enterprise Zone is an empty piece of scrubland near Banjul International Airport, and Enterprise Way does not appear to exist at all.

The entire free-trade zone, complete with its own unofficial company registry, is a fiction conjured up in London by Formations House, a UK-based corporate registration firm, and administered mainly out of its back office in Karachi, Pakistan. Clients paid to register companies in Gambia — using Formation House’s unsanctioned registry, not the official Gambian one — and received fake documents, emblazoned with the seal of the Gambian state but created in Karachi. The main beneficiaries of the arrangement were the family behind Formations House and their business partner, a UK- and Cyprus-based salesman who is still hawking fake Gambian banks to customers around the world.

Drawing on a trove of leaked emails obtained by the information activist group Distributed Denial of Secrets and shared with journalists, OCCRP pieced together the story of how Formations House established a foothold in Gambia by ignoring local laws and at times outright breaking them.

Gambian officials investigated the fake registry and tried to shut it down, but their efforts were stymied for a simple reason: The heart of the operation was nowhere near Africa. Since the Gambian zone, and the companies within it, were invented by British people in the middle of London — and sold online, often via email — it could only effectively be shut down by UK authorities.

This dilemma highlights the outsized role the British company formation industry plays not just at home, but around the world. Regulatory lapses in the United Kingdom can have serious consequences in countries that — even when they notice the wrongdoing — have no recourse but to appeal to London for help. Gambian officials told OCCRP they had investigated and contacted Interpol UK for assistance in the matter. (The National Crime Agency, which oversees Interpol UK, had not responded to a request for comment as of press time.)

The email records examined by OCCRP span a ten-year period, from 2008 to 2018, during which time the founder of Formations House was investigated by British police for serious financial crimes and the UK’s top anti-money-laundering regulator, HM Revenue and Customs, warned the company that it could face prosecution for its failure to comply with regulations. But Formations House is still doing business today.

Maira Martini, a policy and research expert at Transparency International who focuses on corrupt money flows, said the fake Gambian registry was a good example of why the UK needs to better supervise companies operating on its territory.

“If, in 2016, there were already investigations into them and they were criticized for their lack of due diligence and so on, and nothing really happened to them and they continued doing business as usual, something is wrong with the sanctions regime in the country,” she said.

“It cannot be that a company gets to make so many serious mistakes before they have to improve their standards.”

HM Revenue and Customs declined to comment on the outcome of its investigation into Formations House or any follow-up actions it might have taken, saying it was unable to discuss issues related to any specific business.

In an email response, Formations House owner Charlotte Pawar said the leaked data had been reported as stolen and that the firm has faced extortion attempts. She did not provide evidence to support these claims, despite several requests from journalists. Pawar also said Formations House had improved its compliance processes since being warned in 2016.

What is a Corporate Registry?

A corporate registry is responsible for keeping records of all firms licensed to do business in a given jurisdiction, and managing their formation and licensing. In most countries, including Gambia, maintaining such a registry is a government function. Gambia’s corporate registry is called the Single Window Business Registration Department, and is run by the Ministry of Justice.

From London to Gambia

In April 2013, a Senegalese-Canadian named Mouhamadou Mouctar Diagne sought a meeting with Gambia’s authoritarian ruler, Yahya Jammeh, for himself and his business partner, Nadeem Khan, a British-Pakistani entrepreneur who founded Formations House in 2002.

A year prior, Diagne had launched a construction project to build houses in Kanilai, President Jammeh’s home village and the center of his network of power and patronage. It was never completed, but his company, Management Holding MHL, did build a few private houses in Jammeh’s compound.

Now, he appeared to be reaping the fruits of his investment. Diagne and Khan were invited to a private meeting with Jammeh at the State House, where they made a strong pitch to be allowed to create the tiny West African country’s first free-trade zone.

“The impression given was that they had the capacity and know-how to develop the free zone as a hub for international investments, for the benefit of The Gambia,” recalled Dr. Njogu Bah, a top aide to Jammeh at the time.

A month after that meeting, the parties had come to a provisional agreement. The Gambian state said it would grant 500 hectares of land near the Banjul airport to Infini Africa, a Seychelles-registered company co-owned by Khan and Diagne. Photographs of the two businessmen sitting with Jammeh were published in Gambian newspapers, accompanied by headlines announcing lofty plans.

Infini promised that what it dubbed the “Enterprise Zone” would generate 360,000 local jobs with its new facilities, including Africa’s largest media studios, 1.5 million square feet of warehouse space, another 2.5 million square feet of retail and office space, luxury apartments, and 5,000 hotel rooms.

None of that came to fruition.

Infini also said it would create a high-tech corporate registry, iCommerce, that would register 100,000 firms by 2017 using a cutting-edge “cloud based E-Government system.” It claimed the project would bring in $546 million in annual revenues for the government, and make it “the easiest place in the world to start a business.”

The iCommerce registry did materialize, but in a very different form than promised. Instead of creating a high-tech corporate database for Gambia and sharing its profits with the Gambian government, Formations House moved forward on an unsanctioned Gambian registry that registered thousands of companies without government approval. There is no evidence it ever shared these proceeds with the Gambian state — which recognizes none of these companies.

Five hundred million dollars would have been a substantial sum in Gambia, the smallest country in mainland Africa, and one of the poorest. In 2013 it was still ruled by Jammeh, a deeply corrupt dictator who had come to power in 1994 in a coup d’etat. (He was ousted in 2017 and is now living in exile in Equatorial Guinea.) Gruesome testimonies of rights abuses under Jammeh continue to emerge, implicating the ex-leader in systematic rape, torture, and repression of his political opponents.

But according to Infini, Gambia was a “stable democracy.” The West African nation was “famous for its pristine beaches and eco-tourism,” the company sunnily proclaimed on its website. Most importantly, the English-speaking nation offered “a convenient location for international businesses wishing to be located in the same time zone as London but with significant cost advantages.”

Khan told the Banjul Daily Observer that Infini was “one of the largest software developers in the world” and had offices in London, the United States, Hong Kong, India, and Pakistan.

He did not mention that it was controlled by his family’s corporate registration firm, Formations House, which had already registered tens of thousands of offshore companies in various jurisdictions around the world.

House of Legal Woes

British authorities charged Formations House founder Nadeem Khan in April 2014 with alleged involvement in a 100-million-euro fraud case. He was accused of facilitating money laundering through companies linked to Formations House, including Accounts Centre. But he died in September 2015 at age 54 before he could be tried.

Adding to the murkiness, while Formations House was headquartered in London, OCCRP partner The News has discovered that the entire project was actually being run out of Karachi.

The company’s main staffer handling the Gambian offshore zone represented himself as a European named Oliver Hartmann, but was actually a Pakistani named Syed Rizwan Ahmed.

Another ex-employee, who asked for his name to be withheld because he feared retaliation from the owners of Formations House, said that at the peak of Infini Africa’s operations, there were 150 employees in Karachi working full-time selling Gambian companies or supporting the iCommerce registry.

Pakistani employees were told that Khan — who was known in the office as “Ali London” — had promised Jammeh that Gambia would become “a place to park the money of the rich from across the globe” and that it would “prosper like Silicon Valley.”

As early as June 2013, “Hartmann,” along with the registry’s chief salesman, Michael O’Mara de la Fuente, who ran his own firm but worked closely with Formations House, was heavily marketing their Gambian offshore zone.

“Dear Sophia, I am offering you a chance to make fortune,” he told a prospective client in Russia. “We are introducing GAMBIA as a new offshore jurisdictions offering complete range of business and financial services with minimum compliance requirement and low taxation,” read one such sales pitch, which offered fraudulent banking licenses and company formation “within hours.”

“It has the easiest compliance requirements in the whole world,” Hartmann added.

In December 2014, as the money came in for two of the company’s key early sales, O’Mara sent Hartmann a delighted email.

“We’re celebrating!” wrote O’Mara. “Wish you could join us in a glass of bubbly!”

Trouble in Paradise

But even as they toasted to their success, the group had a serious and growing problem: The deal between Formations House and the Gambian government was not legal and never had been.

Although they had inked a provisional contract allowing iCommerce to operate from the proposed offshore zone, the agreement was never formally gazetted, and never passed into Gambian law.

Without the legal framework to turn the land into a tax-free zone, there would not be any media studios, luxury apartments, or high-tech servers. All Formations House had was an empty field on the outskirts of Banjul and a worthless photocopy of a preliminary agreement with the president.

Undaunted, employees started to register companies in Gambia at a fast clip, with this document as their only basis for doing so. Many of the firms were listed at One Enterprise Way, which does not exist and never has, according to two Gambia Post officials who spoke with OCCRP.

Formations House advertised its ability to create a registration certificate for a Gambian firm within days, for the cut-rate price of just 195 pounds. All of the documents issued by Formations House’s Gambian registry were signed by a man named Aziz Kebe, who alternately went by the titles “registrar” and “compliance officer.”

But the chief registrar of Gambia, Alieu Jallow, told OCCRP he had never heard of such a person. He examined a company registration certificate issued by iCommerce and signed by Kebe, and confirmed it was fake.

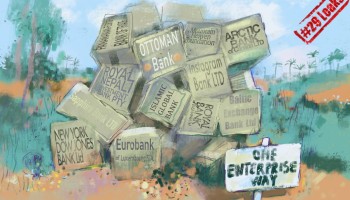

Formations House also used the Enterprise Zone to create fake banks for its clients. In reality, these entities — some 150 in all — were ordinary shell companies made to look like legitimate financial institutions by tacking the word “bank” onto their names.

For a while, the business flourished. But one of these fake banks eventually caught someone’s attention.

In 2015, a group of people working with a so-called bank in the new trade zone grew suspicious. They retained a prominent Gambian law firm, Amie Bensouda & Co, to look into iCommerce.

Immediately, Bensouda’s son Aziz told OCCRP, “We realized something was wrong.”

Aziz Bensouda, who is also a lawyer, said he feared Gambia’s international business reputation would be dented by Formations House’s activities.

“If you drive past the airport, nothing is there,” said Aziz Bensouda. “They created this fake universe of story buildings and hotels.”

Amie Bensouda got in touch with the Gambian Central Bank and the Department of Justice, which regulates Gambia’s sole authorized corporate registrar. Both institutions said iCommerce was operating illegally.

Spurred by Bensouda’s inquiries, the Gambian government formed a task force to look into the matter, and the real corporate registry reported it to the police, asking for a formal investigation to discover who was behind iCommerce. The Department of Justice posted a notice on its website disavowing the registry and the entire Enterprise Zone.

Emails show Formations House staff scrambling behind the scenes to contain the damage. Pawar, Khan, Hartmann, and O’Mara fought to prevent Bensouda’s revelations from becoming public, while debating if there was anything they could still do to get Gambian authorities to legally recognize the offshore zone.

They didn’t have many ideas.

The group had apparently underestimated the complexity of Gambia’s political landscape, assuming that Jammeh’s personal approval would be enough to push their plans through. Several emails suggest that Formations House had been asked for large sums of money to get the process moving again. And their internal messages make it clear they knew the registry was not a legal enterprise, even as they continued to add fake companies and banks to it.

O’Mara, as the primary public-facing member of the operation, appeared the most concerned. In June 2015, he sent urgent emails to Khan and Pawar underscoring the gravity of the situation. He demanded that they show him the original contract they had signed with the Gambian government.

“DOES SUCH A DOCUMENT EXIST?” he asked in red capital letters. “IF SO, WHAT KIND OF DOCUMENT IS IT? WE NEED TO SHOW IT IMMEDIATELY.”

In a follow-up email in August, he accused Bensouda of spreading “rumours” and warned that the whole scheme was “like a mirror”: “It cracks unless we are able to get the authorities over there to acknowledge the [zone].”

DANGEROUS WAR OF WORDS

“We Cannot Pay for Anyone Else to Be Involved”

Nadeem Khan became seriously ill in 2015. His daughter, Pawar, took charge of the Gambia venture, but she had inherited an unpleasant situation. The offshore zone seemed no closer to being legalized, and Formations House was being bombarded with inquiries from nervous clients who had seen the Gambian government notice that the entire project was illegal.

In a message to Diagne in November that year, Pawar said her father had designated her as his successor, but was so sick he was unable to communicate. In fact, he had been dead for two months.

She told Diagne the Gambia project would be shut down if he couldn’t help her get the offshore zone legalized.

“We need to get this project back on track, this isn’t something we can fix by throwing more money at it, as you know we have all spent too much to end up in the same position, No Gazette and no actual update to the law, meaning the Enterprise Zone can't officially continue to register companies and certainly cannot attract the foreign investment they wanted to develop the land make the millions we have been discussing,” she wrote.

“The issue as I see it is too many ministers and changes, and for this to work the word from above needs to be followed and signed off. We cannot pay for anyone else to be involved.”

Diagne told OCCRP that Infini Africa was never solicited for a bribe by Gambian officials, and Pawar did not respond to questions on whether Formations House had paid or been solicited for bribes. But at least two emails discuss having been asked for a $500,000 payment to get the BEZ project moving again.

“This is not an option for us as we don’t have that kind of money,” Pawar said in one message.

Pawar also claimed to Diagne that Formations House was no longer accepting new clients or taking payments for company registration in Gambia. However, internal emails show the company was continuing to register companies all the while, with funds going straight to the family’s UK businesses.

But Gambian law is not so simple, according to Bensouda. Although gazetting was indeed a key step, a new offshore zone would be a complex endeavor that would have to pass through many other stages, including parliamentary debate, before it could be legalized. The Enterprise Zone agreement was still in a vestigial state.

“It can’t be gazetted because it’s just a document created by PDF by God knows who,” he said.

O’Mara betrayed this misunderstanding when, several months later, in another anxious email to Formations House, with the subject line “Getting Our Ducks in a Row,” he suggested the group could publish a notice about the BEZ in a legal gazette themselves if the Gambian government remained recalcitrant.

He asked again to see a clear copy of the agreement.

“When people attack the legitimacy of the BEZ & the registry, I only have the contract copy with Infi [sic] Africa to show (it's pretty blurry),” he said. Hartmann forwarded the email to Pawar. There is no record of a response.

In November 2016, still reeling from Bensouda’s revelations and the Gambian government’s pushback, Pawar began to explore the idea of transferring the Gambian “banks” and shell companies to Cape Verde or Gabon.

The plan, as laid out in the leaked emails, would be essentially identical to the one Formations House pursued in Gambia: Create an unregulated offshore zone and register as many companies there as possible. But there would be one crucial difference, Pawar said: “gazettes and central bank authorization will be in place prior to issue of any licences.”

OCCRP could find no evidence the Gabon plan moved forward, and the leaked emails end in 2018. But Michael O’Mara is still selling Gambian banks to this day, using the fraudulent structure created by Formations House, despite Gambian officials’ protestations that the iCommerce registry is unsanctioned and illegal.

Pawar did not respond to specific questions about the company’s Gambian operations, other than to insist that the iCommerce registry was legal and the Gambian government had never said otherwise. She also said she was no longer involved in the country.

Dr. Seeku Jaabi, the deputy governor of Gambia’s Central Bank, said in response that iCommerce was totally illegitimate.

“iCommerce whatever, eCommerce whatever, or any other person can not register a business, a banking business, in Gambia,” he said.

As Gambia tries to move on from decades of dictatorship and corruption under Jammeh, the legacy of Formations House’s hall-of-mirrors registration scheme could have lasting repercussions.

The full scope of the fraud unleashed by the sham companies of One Enterprise Way may never be known, but the registration documents generated by Formations House looked realistic enough to fool even a careful observer — and an untold number of these ghost companies and banks are still out there.

“Definitely the Gambian people are the ones who are really hurt,” said Transparency International’s Martini.

“If you have a lot of fake companies or banks set up there...how would you actually be able to attract real investment?”

Aziz Bensouda said the proliferation of fake banks had made it harder for ordinary Gambians and legitimate local companies to do business. In particular, many large international banks will not provide services for Gambians. He acknowledged that this was due in part to the country’s generally high risk profile for money laundering.

“But,” he added, “it might also be because of these ghost banks in Gambia that don’t really exist.”