The average Turkmen cannot have cars such as BMWs or Mercedes, the most prestigious cars that can be purchased in the country, although there is no official ban on those cars, according to the Turkmen News, an independent Turkmenistan’s news outlet and human rights organization based in the Netherlands.

However, if ordinary people own such vehicles, they cannot take them to a regular, “annual technical inspection for unclear reasons.”

Earlier this year the outlet also reported that the Turkmenistan's traffic police stopped issuing car plates for “Mercedes, Audi and BMW cars manufactured in 2016 and later, although they meet all the requirements of the customs service.”

Technicalities, according to Turkmen News sources, have not been the real reason. Rumour has it that the members of the “presidential clan don’t want anyone to drive the same cars as them.”

Some of them even brag about their luxurious four-wheelers and enjoy sharing photos of those shiny vehicles, like Berdimuhamedow’s distant relative Kemal Rejepov.

A single BMW X4 M Competition was not enough for him, so he added BMW 540, Toyota Land Cruiser 5.7 VXR, Lexus GX 460 and several other luxurious cars to his collection, next to a collection of expensive watches he also fancies.

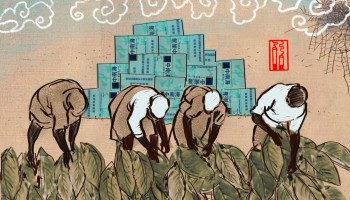

The owners of such expensive vehicles, however, do not like being mentioned in the media. Nurgeldi Halykov, 26-year-old Turkmenistan reporter, was jailed for four years for sharing a photo with an independent news outlet. (Photo: Turkmen News)

Nurgeldi Halykov, 26-year-old Turkmenistan reporter, was jailed for four years for sharing a photo with an independent news outlet. (Photo: Turkmen News)

“When I published the article I received a threat from an unknown person or persons,” the Turkmen News director, Ruslan Myatiev, told OCCRP Wednesday.

Myatiev was told “to think about his own ‘clan’ in Turkmenistan,” especially his mother-in-law, his only relative living in the central Asian country, suggesting to him that “there could be a car accident or a brick might suddenly fall on her.”

He was also given 24 hours to remove the story from the outlet’s website, which he refused to do.

The source of the threat was traced back in Turkmenistan, according to Myatiev.

The threat, as he said, did not scare him, but rather alarmed him, as it was unlike previous threats he had received, in its precision and detail.

Turkmenistan is the third most censored country in the world, after North Korea and Eritrea, according to a list compiled by the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ) last year.

Myatiev also stressed that his colleagues, reporters in Turkmenistan, live out the dangers of existing under an oppressive regime from day to day. He underlined the case of a young, 26-year-old Nurgeldi Halykov, who was jailed for four years for forwarding a photo of a World Health Organization (WHO) Delegation visiting Turkmenistan in July, to Turkmen News.

Halykov had not even taken the photo himself, but got it from his friends, who also ended up being questioned by police.