On an October evening in 2018, as Sebastiano Giorgi and a Romanian associate skipped and swayed at a fancy Stuttgart nightspot, they were blissfully unaware that their every move was being eyed by police. The cops had watched the pair polish off a meal before following them and their “dates” onto the dance floor, believing the gangsters were meeting up to talk about drugs. In fact, they were busy with the sex workers they had taken out on the town.

German authorities and Italian anti-mafia police had been watching Giorgi — known as “Bacetto,” or “Little Kiss” — for years. A rising figure in Italy’s 'Ndrangheta criminal organization, he was based a two-hour drive away in the picturesque lakeside town of Überlingen, where he ran an Italian eatery frequented by tourists. While Bacetto’s restaurant hasn’t always earned the best reviews from diners, he does get high marks from investigators for his other business — managing a multi-million-euro cocaine pipeline from Latin America to Europe.

Back in the 'Ndrangheta’s spiritual home of San Luca in Italy’s southern Calabria region, the Giorgis — known as “Boviciani” to distinguish them from other local Giorgis — had hammered out alliances with top 'Ndrangheta families to form a cartel of drug buyers. From his base in southern Germany, Bacetto extended the network to include international gangs who wanted in on the action.

The 'Ndrangheta’s reach stretches well beyond Europe, to Colombian and Mexican cartels. Through brokers in Paraguay and Uruguay — with logistics provided by a feared prison gang in Brazil — they ship drugs to the ports of Antwerp in Belgium, Rotterdam in the Netherlands and Hamburg in Germany, often via West Africa. Once the cocaine hits northwestern Europe, the Italians take control.

IrpiMedia and OCCRP used court and police documents, and interviews with law enforcement sources, to reconstruct a years-long police investigation into a network of Albanians, Romanians, Colombians, Mexicans and Brazilians, spanning not just the ports of Europe, but also the criminal hubs of Latin America and West Africa.

On May 5 this year, the investigation known as “Operation Platinum” culminated with around 800 police and tax investigators arresting 32 alleged mobsters in Italy and Germany. One German prosecutor called it “a bad day for the dark side of power.”

Bacetto’s bad day had already happened nine months earlier.

A family member once jokingly described him as lazy, saying that he “wakes up early in the morning, has a coffee, and then goes back to bed.” And in July 2019, the wanted mobster sleepwalked right into custody after he drove by a military police checkpoint near his hometown and was stopped for having tinted windows, according to a local media report. Military police then arrested him for prior offenses.

Bacetto and other central characters in the following case are still awaiting trial, and allegations outlined by police sources and in official indictments have not yet been proven in court. Multiple attempts to contact a legal team known to have represented the Giorgis have gone unanswered.

The Trail of the Traffickers

The Giorgi-Boviciani Clan

Despite its picturesque waterfront location on Lake Constance in Überlingen’s town center, the Ristorante Paganini garners lackluster reviews. Customers online bemoan the “awful salad,” spaghetti that’s “overcooked and tasteless,” and “a fly in the tortellini,” although one concedes the Italian staff are “friendly enough.”

Paganini rates a lowly 61st out of 62 restaurants in Überlingen on Tripadvisor. But food is not likely the Giorgi-Boviciani clan’s main concern: The 'Ndrangheta cell, investigators say, have established a criminal fiefdom in Überlingen over the past decade, backed by key narco families back home in San Luca.

In particular, the Giorgis are allied with the 'Ndrangheta’s Romeo-Staccu clan, which in turn works under the Pelle-Gambazzas, 'Ndrangheta royalty who lord over one of the three territories into which the group has divided the Italian province of Reggio Calabria.

The ’Ndrangheta: A Global Network

The ’Ndrangheta was formed in the 1860s in Calabria, but grew its power by sending families out around the world via chain migration. Today it’s a global institution made up of affiliated clans working under a hierarchical structure. With major footprints in Italy, Germany, Canada, the U.S., and Latin America, the crime group can affect the price of cocaine around the world.

The Giorgis are no 'Ndrangheta aristocrats, but under this rigid structure, they played a crucial bridging role, buying cocaine from Latin America-based Italian brokers, arranging for it to be shipped to Europe, then selling it to smaller buyers, who distributed it to street dealers. As cover, they used restaurants and an import-export company. Police records show how they used food trucks to move cocaine from the Netherlands and Spain across the continent to Italy.

In Überlingen, the Giorgis were represented by Bacetto and his brother-in-law Sebastiano Signati, while Bacetto’s three brothers — Domenico, Francesco, and Giovanni — remained in Italy. Domenico and Francesco lived in San Luca, and Giovanni lived in Alghero, Sardinia.

According to investigators, the Giorgis imported food from Italy and sold it to other Italian restaurants in Germany, either directly or through retailers, ignoring sales taxes and apparently funnelling illegal profits back home. Some bought the goods out of fear when they heard the name “Giorgi,” a police source said. Others bought them simply because they were cheap.

Though wanted in Italy since 2012, Bacetto operated freely in Germany, where he was tasked with ensuring cash flow for his family, because his Italian arrest warrant was never brought to the attention of international law enforcement, the source said.

According to Operation Platinum investigators and the related Italian order for custody, the Giorgi family would buy food products in Italy and sell them to Italian restaurants in Germany through companies they'd set up there, without paying sales tax. Then the German companies would be closed. At a recent press conference, German chief public prosecutor Johannes-Georg Roth estimated they evaded over two million euros in taxes in total.

Reporters were unable to sample the food during a visit to the Paganini in January 2020 because the eatery was closed for winter. But clues about the Giorgis’ European partners were easy to spot. A mailbox on the building’s left side included a long set of names; some were Giorgis and their Calabrian associates, but three with Romanian surnames made the list as well.

The Cops Catch a Break

Despite their impressive efforts to conceal illegal activities within the legal economy, the Giorgis let themselves down in other crucial areas — especially when it came to their internal communications. They would also be undermined by one-time allies who had decided to speak to police.

Operation Platinum narrowed in on the Giorgis in 2017, when anti-mafia police in Turin noticed a family member stopping in their city as they made their way north from Calabria to Überlingen. The investigation soon involved German police from the town of Friedrichshafen, a 30-minute drive along Lake Constance from Überlingen, who tracked the Italian on the reverse trip south.

The Giorgis used encrypted EncroChat phones, making it impossible to intercept their communications. But Turin investigators caught a break in mid-2018 when Bacetto’s brother Giovanni, who had been under house arrest in San Luca, was granted permission to move to a home in Sardinia. Bugging this property, investigators could listen in on Giovanni’s conversations with relatives and friends, who would make pilgrimages from Calabria or Piedmont to meet the Giorgi family leader.

Bacetto mostly stayed put in Überlingen, striking cocaine deals in Belgium, the Netherlands, and elsewhere with the Romanian, Albanian, and Colombian gangs who play key roles in the drug trade surrounding the ports of Antwerp and Rotterdam.

The high-stakes industry, it seems, put a frequent strain on family relations.

In one bugged conversation with his nephew Antonio, Giovanni slammed Bacetto for keeping too much of his earnings for himself and his associates in Germany, when more should have gone to the cassa comune, a family kitty used to finance drug purchases.

Antonio accused his relatives in Germany of swiping 3,000 to 4,000 euros per day every time they’d "work" — his euphemism for dealing with drugs. He also complained that Bacetto said he didn’t have money for the cassa comune because of expenses for the Paganini restaurant.

Although slighted by his own family in the bugged chats, Bacetto was in fact the “soul” of the Giorgis’ cocaine business, according to a longtime investigator of the 'Ndrangheta who requested anonymity to protect ongoing operations.

Investigators believe it was through Bacetto that the Giorgis were in touch with a key contact: Denis Matoshi, one of the heads of Albania’s Kompania Bello cartel. Matoshi ran a gang of Albanians in Rotterdam and Antwerp, overseeing cocaine shipped via Latin America to Europe.

Giuseppe Tirintino, a longtime 'Ndrangheta trafficker who began cooperating with authorities in 2015, said that Bacetto, armed with a fruit-buyer’s license, had used a refrigerated truck to disguise cocaine shipped through Rotterdam among fruit consignments.

Tirintino said his cousin supplied Bacetto with “the goods,” meaning cocaine, for which the Giorgis paid 32,000 to 33,500 euros per kilogram. He said he had numerous meetings with Bacetto, who travelled far and wide to seal deals, including trips to Rome and Rosarno, in Calabria, as well as to Germany and Spain.

He said the two also met in the Italian coastal city of Genoa, where “the truck was loaded with cocaine that came by sea, in containers.” “They [the Giorgis] had large financial resources,” he said. “They never bought less than 30 kilos of cocaine at a time.”

Bacetto also appeared to see himself as a major player. In an intercepted conversation in a bugged Audi A3 in November 2018, he bragged to his brother and nephew of making 400,000 euros a year “net” and said it took “balls” to accomplish what he had in Germany.

“No one helped me set this up,” he says. “Who else but me could do it?”

The Antwerp Connection

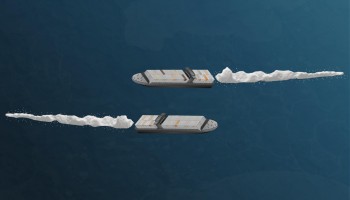

More than 750 million shipping containers are moved by sea annually, accounting for 90 percent of the world’s cargo trade. Fewer than two percent of these are ever screened. In 2017, Antwerp handled up to 3.5 million incoming shipping containers, of which roughly one percent were checked.

As Europe’s largest fruit-handling port, Antwerp has direct cargo lines from Colombia, Ecuador, Guatemala, and Panama. Fresh produce needs to be processed rapidly, meaning customs and law enforcement officers often struggle to screen shipments thoroughly. This makes the port a popular entry point to Europe for drug traffickers. Almost 42 tons of cocaine were seized at the port in 2017, and some 50 tons in 2018. By 2020, this figure had risen to around 65 tons. Each year, dozens more tons are intercepted before they can even reach the port.

Traffickers are also drawn to Antwerp’s easy road access to the Netherlands, a key European market where large quantities of drugs are processed and cut before being sent on to smaller distributors across Europe.

Throughout 2018, investigators tracked Bacetto and other Giorgis on several trips to the Netherlands. During these trips Bacetto met with several suspected drug traders, including the Romanian Adrian Bogdan Andrei, alias “Andy,” whom police identified as Bacetto’s “footman.”

Andy let Bacetto sleep at his Rotterdam apartment and use it as a logistical base as he moved between Amsterdam and Rotterdam to meet with Colombian suppliers. All the while, investigators were on their trail, and mapped out the path of at least one large suspected shipment.

In October 2018, Giovanni Giorgi was heard telling an associate that Bacetto was dealing with “foreigners” in the Netherlands who were expecting a load of about 170 or 180 kilograms of cocaine. Next, in a bugged conversation from an Audi A3 travelling between Überlingen and Amsterdam on November 18, 2018, Bacetto and his brother and nephew discussed how to handle the Netherlands transaction.

The Giorgis owed about “500,” they said — a fee believed by court authorities to be 500,000 euros. This payment needed to be settled ahead of November 25, the day the drugs were meant to arrive in the port of Rotterdam from Guayaquil, in Ecuador. In Amstelveen near Amsterdam, they would meet Andy and two Colombians — who didn’t know they were being tailed by Dutch police.

Wiretapped conversations between Andy and the Giorgis showed how the shipment’s safe arrival would be guaranteed by the detention of a man connected to the Colombian suppliers — a collateral system often used in the underworld.

"One of them stays with us,” Domenico Giorgi was heard to say.

“We come here, we keep him with us, and we search for a house,” Bacetto continued.

“We first give them the money and when the stuff is at the port — ” Domenico replied before Bacetto broke in again: “He stays with us and only when the stuff has been loaded we can talk on the phone, okay?"

And that, police say, is what happened: a young man from Medellín was held captive by Sebastiano Signati at a Rotterdam B&B until November 29, when he was driven back to Amsterdam and handed, along with a backpack, to his Colombian associates. Police wiretaps suggest the backpack held 300,000 euros in cash.

Rather than the expected 170-180 kilogram shipment, investigators believe the final total was 124 kilos, split down the middle between the Giorgis and their Romanian associates. Investigators believe Bacetto and the Giorgis bought 62 kilos of cocaine from the Colombians in the Netherlands, 12 of which were presumably transported to Italy in December 2018.

A few months later, German investigators heard Bacetto talking at his apartment in the town of Seelfingen — which had also been bugged — about another cocaine deal with an Albanian and a Romanian both living in Belgium. This deal, police suspect, involved a shipment of 240 one-kilogram packages of cocaine. Both the Albanian and the Romanian are suspected traffickers based in Belgium, while the Romanian manages a handful of logistics companies there.

Once these shipments had safely made it to Europe, the Giorgis got to work. Transporting cocaine and money in their fruit trucks, police say, they are first believed to have moved around Germany and later headed to Turin, where they were helped by relatives with the logistics.

It was at this Turin stop-off that Italian police, in 2017, had first gotten the whiff of the Giorgis’ trail.

Feeding the ‘Cassa Comune’

Police documents and OCCRP sources in Italy and Germany show how the Giorgis worked both sides of the cocaine trade.

The evidence trail offers a clear breakdown of the family’s drug dealing, from agreements with major players who dealt in tons of cocaine in Latin America, to minions who sold quick highs in the bars of Europe.

Once it arrived in Italy, the Giorgis’ cocaine went to retailers in Turin, Milan, Sardinia, and Sicily for 30,000 to 48,000 euros per kilo, depending on the buyers’ relationship with the Giorgis. These clients were mainly other Calabrians, for whom the family reserved the largest portions of their shipments.

The Giorgi then sold a smaller part to average dealers — bar owners in Turin, Sicily and Sardinia, for example. In these cases, the price climbed up to 57,000 euros per kilo, or between 5,000 and 7,000 euros per 100 grams, according to wiretapped conversations between Giorgi family members.

According to the Operation Platinum order of custody, the Giorgis had enough logistical capacity to supply their clients with drugs on a weekly basis. But not all deals and deliveries ran smoothly, and the Giorgis weren’t powerful enough to exert control over the ports, which were the realm of bigger players.

To unload illicit cargo, they had to rely on Latin American suppliers, their higher-placed Calabrian allies, or other gangs like the Albanians. Often drugs were shipped using the “rip-off” technique, meaning the company shipping the containers had no idea their shipments were used to carry drugs.

Once through the ports, the cocaine began its winding truck routes. Drivers — one was paid 3,000 euros per trip, according to the Operation Platinum order of custody — had to mimic the routes of legitimate food delivery services following pre-planned GPS coordinates to avoid arousing police suspicions. Along the way, drivers in other vehicles would approach the truck in a pre-arranged location and remove the drugs before the truck continued on its route.

The Giorgi family operated like a company, with each of the four brothers putting the cash they earned into the cassa comune, managed by Francesco. Their weekly profit came to around 200,000 euros, according to bugged conversations.

Bacetto relied heavily on family members and other Calabrians to help manage his German operations. Sebastiano Signati, Bacetto’s brother-in-law, first took over the Paganini in 2010, together with another Calabrian. The restaurant‘s ownership often changed hands over the years, but always remained within the same clique of Italians. Calabrian associates also ran two German companies, one of which, GSG Food, owned the Paganini from 2016 to 2018 as well as importing and exporting groceries. The other, G&S Gastro, took over ownership of the business in 2019.

'Ndrangheta money was also hidden in a very literal sense back home. In a bugged conversation, Giovanni, in Sardinia, instructed Francesco, in San Luca, to bury 400,000 euros in cash. Further conversations show the brothers were hiding fortunes in buried barrels, while always keeping at least 500,000 euros handy for regular expenses.

Giovanni warned his brother to spread the bundles of cash around rather than buying them all in the same hole: “Better to lose two to three hours of digging than losing a whole life of work,” he said.

Key Connections to South America

Operation Platinum documents show that the Giorgis had one key supplier: Giuseppe Romeo, nicknamed “Maluferru.” Roughly translated, the nickname indicates someone armed and dangerous. The Giorgis had their own derogatory nickname for him — The Dwarf — but despite such jibes, Bacetto and his crew knew they badly needed the services that he could provide.

Maluferru is the son of one of San Luca’s most feared bosses, the jailed Antonio Romeo, alias “Centocapelli,” a leading member of the Romeo-Staccu 'Ndrangheta clan. Investigators say Maluferru — who appears to have had crucial connections at three European ports — guaranteed the Giorgis “the constant dispatch of huge loads of drugs” from South America.

In the wiretaps, Giovanni Giorgi lamented that Maluferru often resold the “goods” to the Giorgis at inflated prices. On November 26, 2018, Giovanni told Walter Cesare Marvelli, a Giorgi nephew based in Turin: “When The Dwarf told us that he bought at 27 with our money, he bought it at 24 and stole three points.”

Because Maluferru was so good at what he did, the Giorgis bit their tongues. He supplied hashish as well as cocaine, and “has [access to] everything in Holland,” Giovanni can be heard saying.

For long periods, Maluferru remained a ghost to the authorities. The Giorgis, who had been ordering cocaine from him since at least 2018, swapped rumors among themselves that he had been spotted in Brazil, the Netherlands and Mexico, and may even have disguised himself as a priest.

Through Marvelli, the Giorgis had established a connection to two even more powerful suppliers: Italian father-and-son duo Nicola and Patrick Assisi, two 'Ndrangheta mega-traffickers who had been on the run in Brazil for years and were allies of the country’s First Capital Command (PCC) prison-based crime group. Marvelli had hustled hard to win the Assisi family’s trust, knowing they only opened their doors to a select few.

Cracks began to appear, though, when in August 2018 police caught another break. The Giorgis were still using their encrypted EncroChat phones. But they had failed to grasp the subtleties of the new technology — including the key principle that passwords should be kept secret — conversations from Giovanni’s bugged Sardinian home revealed.

In one conversation, Giovanni told Francesco to unlock an EncroChat phone using the password “pecora,” which means “sheep.” While setting up his own phone, another associate said he would use “the same password as last time” — “Maria.”

Remarkably, Giovanni and Marvelli would later start reading their EncroChat conversations with Patrick Assisi out loud, describing the logistics of the operations in detail.

"We have the exit [the cocaine leaving] both from Peru and from Venezuela," Assisi wrote in one message, as read out by Marvelli to Giovanni.

Assisi wanted the unloading done in Hamburg, the message continued, and asked Marvelli to send “a Chinese” person to pick up the shipment.

“He says to me then … ‘Send some guys, so it’s yours, for better or for worse and we’re relaxed, for better or for worse, and we are calm … we know the responsibility is yours,’” Marvelli read out, quoting Assisi.

The bugged chats revealed that the Assisis — who are known to have mostly shipped cocaine in liquid form — would be sending a consignment in 2.5-kilo bags hidden in a shipment of an unnamed mineral. Because the Assisis didn’t handle unloading at European ports, the Giorgis were forced to involve The Dwarf in the process.

The Assisis said they would send a shipment of 500 kilos, according to the conversations, which investigators told OCCRP was because the logistical costs and bribes needed for each load made smaller loads impractical. Import-export companies or the “rip-off” technique provided cover.

Using the trail laid out by the Giorgis and their accomplices, German police identified containers that fit the profile for the would-be Assisi shipment. But when inspections were made in Hamburg in October 2018, no drugs were found. The detectives got luckier a month later, on November 8, when they raided a container suspected of carrying Assisi cocaine bound for the Giorgis, and uncovered 300 kilos of cocaine stashed in packages of cotton swabs.

By October 2018, however, the Giorgis’ Latin American connections were coming under threat.

Around this time, their agreements with the Assisis had begun to hit a roadblock, and Marvelli planned to go to Brazil to meet Patrick Assisi in person. Maluferru, though, had other plans, making a move to cut the Giorgis out, and beginning to deal with Assisi directly. Assisi, it turned out, preferred dealing with Maluferru, who was reliable, invisible, and had the keys to unlock some major European ports.

The Giorgis, constantly walking a tightrope between powerful suppliers whose whims could make or break them, seemed destined to remain effective cocaine distributors with little prospect of ascending to the higher echelons of the 'Ndrangheta. Little did they know, however, that dark clouds were also beginning to hover over both Maluferru and the Assisis, and the pipeline from which they had made their own fortunes.

Luis Adorno, Nathan Jaccard, Benedikt Strunz and Koen Voskuil contributed reporting.

This story was partly funded by grants from Journalismfund.eu and Reporters in the Fields.