When Syria issued its long-delayed third mobile phone license to a little-known operator early this year, officials trumpeted it as a moment of “great hope” for a sector battered by a decade of war and sanctions.

But when it came to naming the figures behind this company, Wafa Telecom, the Syrian government has been more reticent. Since Wafa received its license in February, authorities have said little about the firm’s owners beyond the fact that they are “national” companies — that is, Syrian.

In reality, not only do Wafa’s shareholders include foreign investors, those investors have multiple ties to Iran’s most powerful military body, the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC), an investigation by OCCRP and the Observatory of Political and Economic Networks, a non-profit research institution, has found.

One of Wafa’s owners is a Malaysian company, which, until 2019, was directly owned by a Revolutionary Guard official, corporate records show. Two of the Malaysian company’s current corporate officers are also linked to firms that have been sanctioned for supporting the Revolutionary Guard.

A Syrian businessman and a former government official with direct knowledge of the sector also told OCCRP that Iran was involved in the new operator, with one explicitly calling it “a partnership between the Syrian government and the Revolutionary Guard.”

Iran, a key supporter of President Bashar Al-Assad throughout the war, has made it clear it expects economic payback for its backing. In recent years, it has established interests in Syria’s real estate, ports, and the lucrative phosphates sector, among others.

Joseph Daher, a professor at the European University Institute, said the involvement of Iran-linked figures in the new operator showed “the increasing influence of Iran in the Syrian economy” and represented “to some extent a new loss of sovereignty by the Syrian regime to its allies.”

The revelations may also raise alarm among Tehran’s regional adversaries, given the telecommunications sector’s importance to intelligence-gathering. Various powers have intervened in Syria’s multi-pronged civil war. Russian, Turkish, and U.S. troops are deployed in different parts of the country, and Israel regularly carries out air strikes.

Wafa Telecom, the Syrian Ministry of Communications and Technology, Syria’s Telecommunication Regulator, and Iran’s Foreign Ministry did not respond to requests for comment.

hanohikirf/Alamy Stock Photo

Telecommunications masts on the hillside above Damascus, Syria.

hanohikirf/Alamy Stock Photo

Telecommunications masts on the hillside above Damascus, Syria.

Iran’s Long-Established Interest

When Syria solicited bids for a third mobile license in 2010, it was supposed to be a watershed moment in the liberalization of an economy long dominated by the state. International giants, including France Telecom and the United Arab Emirates’ Etisalat, put down bids. So did an Iranian firm, which Syrian economic experts and media reports identified as the Mobin Trust Consortium, a Revolutionary Guard-affiliated conglomerate sanctioned by the EU and U.K.

Talks moved slowly as authorities and bidders haggled over terms. Before they could settle them, a popular uprising broke out in Syria in March 2011, and the license was put on indefinite hold. As the uprising turned into a full-fledged civil war, Iran supported the Assad regime by funding militias and providing billions of dollars in economic and military aid.

The telecommunications sector has continued to make money over that time, despite a sharp decline in economic activity due to the conflict. In 2021, the country’s two existing operators, Syriatel and MTN Syria, together paid the government around 130 billion Syrian pounds — worth roughly $38 million at the average black market rates at the time — as the “state’s share” of revenues.

Reuters/Alamy Stock Photo

A Syriatel shop in Damascus.

That has made the sector an appealing prospect for Iran. In January 2017, Syrian Prime Minister Imad Khamis visited Iran and signed a memorandum of understanding to grant the third mobile license to the Mobile Telecommunications Company of Iran, or MCI, which was until 2018 partly owned by the Revolutionary Guard through the Mobin Trust Consortium.

But for unclear reasons, that deal never materialized. Statements from Syrian officials reported in the media suggested they were considering other options. They did not give a reason, but Daher pointed out that the sector was particularly sensitive because of its use in surveillance operations.

“In the past, there were rumors Syrian security services were rather uneasy about the prospect of the IRGC gaining access to the country’s telecommunications network,” he said.

Jihad Yazigi, an economist and editor-in-chief of the economic publication The Syria Report, also pointed out that there had reportedly been resistance from Assad’s cousin Rami Makhlouf, the part-owner of the operator Syriatel, who did not want MCI to cut into Syriatel’s market share or use its national roaming system.

Over the following years, Assad’s cash-strapped government moved to assert control over the two existing operators. Starting in mid-2020, authorities accused Syriatel and MTN Syria of owing tens of millions of dollars in back taxes and, when they refused to pay, placed them under the control of state-appointed “custodians.”

Wafa Enters the Scene

When Wafa Telecom was granted the long-delayed third license — as well as a three-year monopoly to run the country’s first high-speed 5G network and permission to use the existing networks of the two other operators — it looked like just an extension of the regime’s efforts to control the sector.

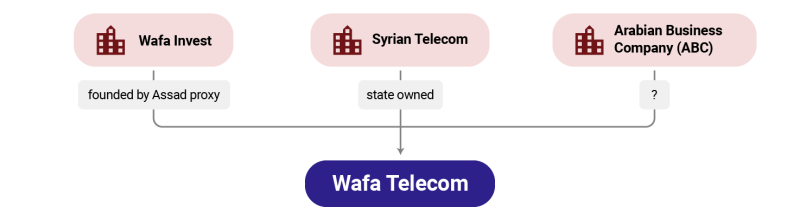

A far cry from the global players who once eyed Syria, the new operator had only been established in 2017. About 48 percent of its shares were held by a Syrian company called Wafa Invest, co-founded by a young presidential aide named Yasar Ibrahim, now 39, who The Washington Post said played a key role in the “mafia-like” takeover of Syria’s telecoms operators.

Ibrahim — who has been sanctioned by the U.S., the EU, and the U.K. for acting as Assad’s financial proxy — did not respond to requests for comment sent through Syria’s presidential media office.

In 2021, Wafa Invest’s stake was reduced to 28 percent, and 20 percent was given to the state-owned Syrian Telecom, making the Syrian government a direct partner in the enterprise.

The remaining 52 percent was held by an opaque company called the Arabian Business Company (ABC), registered in October 2019 in the Damascus Free Trade Zone, where disclosure requirements are limited.

James O’Brien/OCCRP

Syrian officials have declined to identify ABC’s owner. In public statements, they have characterized it as a “national company,” implying it was owned by Syrians, without saying more. But a registry document obtained by reporters shows that these statements were misleading.

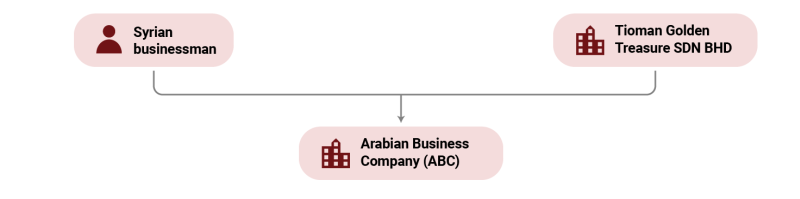

At first glance, ABC’s corporate registration — obtained from the Syrian Ministry of Economy and Foreign Trade — gives little indication of Iranian involvement. Its shareholders are listed as a Syrian businessman and a Malaysian company called Tioman Golden Treasure, founded in February 2013.

James O’Brien/OCCRP

A closer look reveals that Tioman is no ordinary telecoms investment vehicle, and in fact has multiple connections to the Revolutionary Guard.

Up until August 2019, about a year before ABC was registered, 99 percent of Tioman’s shares were held by a U.S.-sanctioned Iranian named Azim Monzavi, Malaysian records show. In its sanctions order, issued in May this year, the U.S. described Monzavi as “an IRGC official who facilitates oil sales on behalf of the IRGC,” including facilitating oil deals between Iran and Venezuela.

The connections did not end there. The owner of the remaining one percent of Tioman’s shares, a Malaysian named Jusephen Binti Antahamin, is also a shareholder in an oil firm called PetroGreen Co. In 2013, PetroGreen was sanctioned by the U.S. for acting as a “primary procurement agent” for Khatam-al Anbiya, an Iranian engineering conglomerate controlled by the Revolutionary Guard.

James O’Brien/OCCRP

A separate filing lists another Malaysian, Chan Che San, as Tioman’s secretary. Chan, a chartered secretary, was also listed as a secretary for PetroGreen, as well as for another Malaysian company called Green Wave Telecommunication.

In 2015, Green Wave was indicted by the United States District Court for the District of Minnesota for acquiring “sensitive export controlled technology” from the United States for Iran. One of the defendants’ guilty pleas later said that this technology had been sent via Malaysia to Fana Moj, a company sanctioned by the U.S. for providing support to the Revolutionary Guard. Green Wave itself was sanctioned in 2018.

Ahead of ABC’s creation, Monzavi’s 99-percent stake in Tioman was transferred to another Iranian investor named Amir Mohammadi. Both Monzavi and Mohammadi were registered under the same address, which was also used as Tioman’s corporate address, in a Kuala Lumpur commercial and residential tower.

Although reporters were unable to establish a direct link between Mohammadi and the Revolutionary Guard, documents show that this was not the first time he and Monzavi were in business together — or with a company tied to the sanctioned Malaysian firm PetroGreen.

James O’Brien/OCCRP

Both Monzavi and Mohammadi appear as shareholders in an Istanbul-registered company called Energy Development, which was founded in 2010 by PetroGreen and its manager, Hossein Vaziri, who was also sanctioned by the U.S. for “acting or purporting to act for or on behalf of, directly or indirectly, the IRGC.”

Turkish company records show that Monzavi took over Energy Development in 2013, and transferred it to Mohammadi in 2019.

Edin Pašovic/OCCRP

Tioman’s shareholders and officers had multiple connections to sanctioned entities.

Furthermore, PetroGreen, Green Wave, Tioman, and a fourth company, Asialink — where Monzavi, Mohammadi, Chan, and Antahamin are also listed as officers — all shared the same registered address: a P.O. box in Kuala Lumpur less than a mile from Tioman’s business address.

Irene Kenyon, a former intelligence officer at the U.S. Treasury Department and now director of risk intelligence at the consultancy FiveBy Solutions, said Tioman had many hallmarks of a front company: A vague business purpose, overlapping addresses, little online presence for its key officers, and few listed employees despite nearly a decade in existence.

“All of this combined, it screams ‘shell or front company’,” she told OCCRP, adding that the multiple links between Tioman’s officers with Monzavi and other sanctioned entities “scream ‘Iran,’ at the very least, if not ‘IRGC.’”

OCCRP made repeated attempts to reach Monzavi, Mohammadi, Antahamin, and Chan by voice, text message, and email using phone numbers and email addresses associated with them in corporate records. Chan declined to comment. The others did not respond.

Why Malaysia?

Economic Payback

A former Syrian official with direct knowledge of the telecommunications sector, who requested anonymity out of fear for his safety, told OCCRP that Wafa Telecom’s majority owner, ABC, had been set up in the Damascus Free Trade Zone partly to mask Tehran’s involvement. “They did everything possible to conceal the Iranian ownership,” the former official said.

Analysts pointed to several reasons Iranian authorities might be keen to disguise any investment in Syria’s telecoms sector — to avoid attracting the attention of sanctions enforcers, for instance, or so as not to scare off customers who might be wary of a phone network affiliated with a foreign military power.

Sipa US/Alamy Stock Photo

Syrian Telecom building in Aleppo, Syria.

“Generally speaking, the IRGC, to my knowledge, has not publicly spoken of any project it is involved in in Syria, and in general the Iranians are being careful to hide parts of their operations in Syria,” Yazigi, the economist and Syria Report editor, told OCCRP. “I’m not surprised they are generally low-profile.”

Still, Syria has a strong motive to show its gratitude to Iran after it helped Assad avoid the fate of his counterparts in Tunisia, Libya, Yemen, and Egypt. In May 2020, a prominent Iranian lawmaker, Heshmatollah Falahatpisheh, said that the total cost of Iran’s support for Syria had been between $20 billion and $30 billion — and that they expected to be paid back.

Syrian officials have heeded such statements, at least in rhetoric. In May this year, Fahed Darwich, head of the Syrian-Iranian Chamber of Trade, told a state-run TV channel that “our sister Iran is a sister in everything.”

“When we were at war, we fought together. They stood with us throughout the war and throughout our economic situation. Of course, they get preference and priority in terms of taking part in investments.”

But in practice, things have not always been simple. Although Iran has established interests in several key sectors, deeper involvement has been hindered by sanctions, conflict, and competition with Assad’s other major backer, Russia, for contracts.

There are indications that even Wafa Telecom might not prove very profitable. The company was originally scheduled to begin operating in November this year. But in September it said the launch would be delayed indefinitely.

When it does launch, it remains unclear who will supply the company’s equipment. Three technology experts said China’s Huawei or ZTE could act as providers through regional subcontractors, but both companies denied this to OCCRP.

And although Syria has enough users to support a third operator, the dire economic situation casts further doubt on how much money could still be milked from the sector. Younis Al-Karim, a Syrian political analyst based in Strasbourg, pointed out that even the basic elements needed to run a 5G network, like electricity and fuel, are in short supply in Syria.

“The collapse of Syrians’ living conditions makes the attainment of a 5G network service a luxury,” Al-Karim said. “Who is going to spend on communications if they cannot secure their basic needs?”

Khadija Sharife (OCCRP), Roshanak Taghavi (OCCRP), and Kelly Bloss (OCCRP) contributed reporting.