The Chechen Republic is one of Russia’s poorest regions, its budget supported largely by assistance from the central government.

But the republic’s power brokers don’t hesitate to flaunt their wealth. Ramzan Kadyrov, Chechnya’s longtime Moscow-backed leader, loves thoroughbred horses and exotic animals and invites Hollywood stars to his birthday parties. His daughter hosted a fashion show in Paris. And until he was banned from the site, he used to fill his Instagram page with shots of himself in expensive cars and luxurious interiors.

Kadyrov says that his money comes from God. But Chechen elites also have more worldly sources of income. Reporters from The Project, an independent Russian publication and OCCRP partner, have catalogued multiple business disputes in which a little-known Russian businessman, Pavel Krotov, has stepped in to broker a resolution — only to end up with a considerable portion of the assets.

In each lucrative case, sources say, Krotov was representing the interests of Adam Delimkhanov, a member of the Russian parliament and among the most powerful politicians in the Chechen Republic after Kadyrov himself.

The contours of several of these stories have been reported separately. But emails sent and received by Krotov and obtained by reporters, as well as new interviews with inside sources and corporate and property records, show that his involvement in each of these disputes was part of a larger pattern.

An authenticated police document appears to confirm what multiple sources are too afraid to say on the record: Krotov’s methods included strong-arming the opposing parties. While investigating a formal complaint against Krotov, police noted that the businessmen used “unjustified criminal-law methods of influence.” In interviews, half a dozen sources told reporters that Krotov had a pattern of invoking his connections to Delimkhanov, which is why they feared for their safety and refused to let reporters use their names.

Nor did any of the main parties to the business conflicts described in this story agree to speak to reporters on the record. A majority of those who were contacted refused to speak under any circumstances.

Krotov himself denies any ties to the Chechen politicians, dismissing reporters’ questions as “pure nonsense.”

“I’ve never been any kind of negotiator,” he said. “I do business. I work to create.” Krotov said that all his investments were made with his own money and that he does not know Kadyrov or Delimkhanov. “As an Orthodox Christian Russian person, I definitely don’t work for any Chechen elites,” he said. He also denied many specific claims in the cases where he allegedly resolved disputes.

Representatives of Delimkhanov and Kadyrov did not respond to requests for comment.

“Closer Than a Brother”

Ramzan Kadyrov has been generous in his praise of Adam Delimkhanov. In fact, Kadyrov once referred to the legislator as his successor. “I’ve prepared a person who can replace me,” he told an interviewer in 2009. “Adam Delimkhanov. My closest friend. Closer than a brother.”

In the 1990s, Delimkhanov reportedly worked as a driver for Salman Raduev, a notorious Chechen terrorist who took hundreds of civilians hostage during the first Chechen war. But Delimkhanov switched sides in 1999, taking part in operations against Chechen militants and even surviving an assassination attempt.

In the 2000s he served in Chechnya’s interior ministry, eventually becoming the republic’s first deputy prime minister in charge of security issues. In 2007, he was elected to the State Duma, the lower house of the Russian parliament.

The Russian media has linked Delimkhanov to several killings of Kadyrov’s enemies, though he has never been charged with murder in Russia. In 2009, Dubai authorities accused him of murdering a former Chechen general. Delimkhanov, a member of parliament, was on Interpol’s wanted list for several years. He has denied all these charges.

In 2014, he was sanctioned by the United States for connections with the Brothers’ Circle, a regional organized criminal group.

Collecting a Debt

The first known episode in which Pavel Krotov appeared to act on Delimkhanov’s behalf arose in 2010.

Filaret Galchev, the billionaire owner of Eurocement Group, Russia’s largest cement producer, was in a tough spot. In 2007, Galchev had bought out a partner’s minority share of the business for US$1 billion, agreeing to pay annual installments of $200 million.

But, having made the first two payments on time, he missed the third. Galchev’s former partner first took him to court, then grew tired of waiting and sold the remainder of his debt at a discount. The right to demand payment from Galchev for the remaining sum of $600 million was purchased by Krotov, a businessman who at the time was registered only as the CEO or co-owner of smaller companies with no major assets.

Once Krotov got involved, Galchev found a way to pay his debt almost immediately.

At the time, citing unnamed sources, the Russian business media reported that Krotov was a representative of Delimkhanov, with few further details.

Now, evidence newly obtained by The Project confirms this earlier reporting, linking Krotov with Russia’s most powerful Chechens.

“A Few False Entrances”

Four people who have had business relations with Krotov confirmed to reporters that he was a representative of Delimkhanov. None allowed reporters to use their names, citing safety concerns.

Reporters also obtained thousands of private emails sent and received by Krotov. The emails show that his interlocutors understood him to be acting on behalf of Delimkhanov.

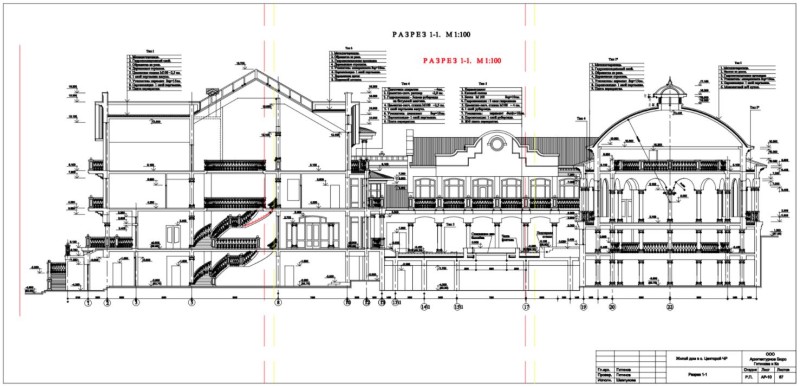

They also show that Krotov had ties to Kadyrov. In the late 2000s, he was involved in the management of the construction of the politician’s residence. The correspondence discussed such details as the building’s budget, its design, and its security features.

In the correspondence, Krotov receives recommendations from a contractor on how best to secure the Chechen leader’s compound: “it is better to bring the bunker out beyond the perimeter of the building and connect them with underground passages. Ideally, none of the staff should know where the entrance to the bunker is located. Maybe it’s worth organizing a few false entrances,” the attachment to one email reads.

“From the point of view of safety,” it continues, “it’s bad to place the President’s apartments above the administrative spaces, since it is theoretically possible to bring an explosive device in there.”

One of the people involved in the construction work also told reporters that Krotov was “working for Delimkhanov.”

Closing a Case

In response to reporters’ questions about the Galchev affair, Krotov said that the deal took place strictly within the law and that “nobody beat anything out of anybody.”

A few years later, Krotov appeared in another legal dispute.

This one also involved a locally influential figure: Yakov Rovner (also known as Yan Rovner), a major land owner, property developer, and “honored citizen” of Kotelniki, a small town just outside Moscow.

In 2011, Rovner got into a confrontation with the Moscow government over a plot of land not far from the city’s ring road. The capital’s new mayor, Sergei Sobyanin, had launched a program to build transport hubs, and one of these complexes was supposed to appear on Rovner’s land. But the businessman and the Moscow government could not agree on the specifics of the project, leading to a series of court cases.

Rovner had powerful connections: The wife and son of the deputy head of the Moscow department of the FSB, Russia’s security agency, were reportedly among the shareholders and managers of his companies.

Nevertheless, in short order, a criminal case was launched against the businessman for fraud and other crimes. Rovner left the country and was declared wanted by the Russian authorities.

Rovner’s problems were solved a few years later — after Krotov became his business partner.

First a Seychelles-based firm called PVK Investments — which, according to Krotov’s emails, appears to belong to him — took partial ownership of the corporate structure that owned the disputed property. In the summer of 2014, the plot of land was sold to another developer, who reached an agreement with the city.

In an email addressed to Krotov and several others, Rovner makes the stakes of the arrangement clear. “I remind you that the subject of our deal, a commitment from your side, was, within 3-7 days of the deal, to remove [me from the] Interpol [list] and then to close the [criminal] case.”

Though Rovner was frustrated by how long it took — “TODAY this has not HAPPENED!!!,” he writes — in the end, the charges against him were dropped.

Other Acquisitions

The correspondence makes clear that, while discussing the deal that would get him out of his predicament, Rovner understood Krotov to be representing someone more powerful.

“Pasha [Pavel Krotov] doesn’t decide anything … All questions should be resolved directly with Adam, who will give Pasha instructions. Whoever Adam says to work with, we will,” Rovner wrote in one email, appearing to refer to Delimkhanov. In another, impatient with slow progress, Rovner demands a conversation with “A,” describing him as his “partner” and a “[Duma] deputy.”

Krotov would not comment on the case or on his ties to Rovner.

Returning a Share

Soon afterwards, Krotov appeared in a story that started in Central Asia.

In 2014, Kazakhstani billionaire Kenes Rakishev, the son-in-law of a former prime minister, acquired an initial stake in BTA Bank from the government.

BTA is a lender with a rich history. In the 2000s it belonged to another Kazakhstani billionaire, Mukhtar Ablyazov, who later feuded with then-President Nazarbayev, was accused of stealing from the bank, and fled the country. The bank was temporarily nationalized, and its new administration started hunting around the world for its lost billions.

Over the next few years, Rakishev gradually grew his share of BTA into a controlling stake and transformed the institution, shedding its banking business. In effect, he turned BTA into an investment company whose main assets were its claims against Ablyazov, estimated at $6 billion.

A considerable portion of the Ablyazov property that BTA was claiming is located in Russia, including plots of land, development projects, and a port. Even before Rakishev entered the picture, a fierce battle over the assets was under way.

Once Rakishev did get involved, Ablyazov’s own investigators found that he was working with people close to Ramzan Kadyrov, including Krotov. An Ablyazov acquaintance told reporters from The Project that Krotov played the role of someone who “could kick your ass, if needed.”

The Ablyazov acquaintance also said that the Chechens went on the attack, demanding that Ablyazov’s assets be transferred to Rakishev.

Rakishev and Kadyrov have known each other since the mid-2000s, and frequently appear in photographs together.

In a Facebook post, the Chechen leader heaped praise on Rakishev: “He helps our people a lot, he often visits me, always shares with me his joys and sorrows. He’s well-known and respected in Chechnya. The people call my BROTHER a prince.”

The Russian company register shows that at least one major BTA asset — Vitino, an oil port on the White Sea in Russia’s north — was indeed returned to Rakishev’s bank with Krotov’s involvement. In 2015, the port was acquired by Vitino Management Company, which is now partially owned by BTA.

One of the two founders of Vitino Management Company was Dmitriy Shivkov. According to Krotov’s correspondence, Shivkov is the brother of his wife, Yana Shivkova, an actor who has performed dozens of small roles in Russian films and television series, including Brigada, a cult hit about the criminal underworld.

Aside from the family connection, emails show that Shivkov helps Krotov in his business dealings. Among other things, he represented him in negotiations with Rovner, the Kotelniki landowner.

Krotov told reporters he never worked for Kenes Rakishev, has no connection to BTA Bank, and doesn’t even know where Vitino is.

Specialized Steel

In 2018, Russian business daily Kommersant reported that Krotov had acquired two major industrial facilities: The Red October steel works in Volgograd, the country’s largest producer of specialized steel, and the historic Zlatoustovsky Electrometallurgical Plant in the Chelyabinsk region.

Here, too, the previous owner of both facilities, Dmitriy Gerasimenko, had gotten into trouble. Red October had gone bankrupt and, he claimed in an interview, unknown operatives had attempted a takeover. He tried to resist but was charged with fraud and fled the country.

The newspaper noted that Krotov was known to be connected to both Kadyrov and Delimkhanov. The Project contacted sources involved in the affair, one of whom confirmed the Kommersant story’s depiction, adding that Krotov had gotten in touch, offered to help resolve the dispute, and ended up with the Zlatoust factory.

In the Russian company registry, the beneficiary of the Zlatoust plant appears to be a proxy, since he is an unknown figure who is also registered as the founder and director of nearly 200 other companies. But Krotov is listed as the facility’s president on its website, and in press releases he is referred to as its “controlling shareholder.”

Krotov denied acting as a negotiator on anyone’s behalf, telling reporters that he had simply purchased the Zlatoust plant.

Methods of Influence

A formal complaint against Krotov and his associate alleges that he threatened people in yet another corporate conflict.

In 2015, both the Moscow and St. Petersburg-based law offices of Egorov Puginsky Afanasiev & Partners — a prestigious law firm one of whose founders was Putin’s classmate in university — reportedly received some unpleasant visitors.

The firm was representing one side of a conflict between two of the co-founders of Karat, a major fishing conglomerate. In 2003, one of the men, Alexander Tugushev, went into government service and — depending on differing versions of the affair — either sold his portion of the holding or turned it over to outside management. He was later convicted of fraud and sentenced to several years in prison. After his release, Tugushev demanded his share of the company back, sparking a multi-year legal battle with Vitaliy Orlov, another founder, whom the law firm was representing.

According to a police document, Krotov visited the law office on more than one occasion, demanding that Orlov return Tugushev’s shares.

One of Krotov’s associates on these visits was a man named Artem Begun, a business partner of Ilya Traber, a St. Petersburg businessman frequently described as a powerful criminal boss with the nickname “Antikvar.”

On one occasion, in an apparent threat, Begun mentioned Adam Delimkhanov and “his people, who use machine guns when they solve problems and remain unpunished.”

In the police document, investigators wrote: “As pressure on the applicant [Orlov], Begun A.A. and Krotov P.V. expressed their intention to arrange for the application of unjustified criminal-law methods of influence against him with the use of high-ranking officials and people close to criminal structures.”

Despite the efforts of Krotov and his forceful associate, the conflict between the two co-founders has yet to be resolved. It is now continuing in a London court. For his part, Krotov denies knowing Tugushev and says he was not involved in the dispute.

A Successful Troubleshooter

It’s unknown how much Krotov has made from his relationship with Delimkhanov and other Chechen elites. But the businessman lives in style. “He’s friends with everyone, goes to the banya with everyone,” says an acquaintance, referring to the Russian sauna, where power brokers might discuss matters of importance. “He drives a Rolls-Royce and creates a high status for himself.”

Krotov and his wife own a large property with a villa in the Rublevka, an area near Moscow where many Russian elites own luxury homes. Similar properties in the same estate, Landshaft, are now selling for over $8 million

An online advertisement for a used car for sale shows a Porsche Cayenne in front of Krotov’s house: “Infrequent and careful usage (the family has six automobiles),” the ad reads.

Krotov and his wife also own an almost 300-square-meter apartment worth almost $3.5 million in Moscow and two apartments worth nearly $3 million in Sunny Isles Beach, a city in Florida that has become popular with wealthy Russians. Judging from his correspondence, he also has an apartment in Paris worth close to 6 million euros and another in Cannes, on the French Riviera, worth over 1 million.

Aside from wealth, it’s possible that Krotov has also enjoyed some level of diplomatic immunity in his own country. As recently as last month, he was listed on the website of Grenada’s embassy in Moscow as the Caribbean country’s trade attache.

On the site, Krotov was described as a “specialist with more than 25 years’ experience in the area of corporate deals,” a “highly productive implementer with verified experience reaching mutually beneficial commercial deals,” and a “strong communicator.” His profile was removed from the Grenadan Embassy’s site shortly after reporters sent inquiries about his work there. The press office of the Russian Foreign Ministry said it had no record of Krotov being accredited as a trade attache.

In response to reporters’ inquiries, Krotov declined to discuss his work for the government of Grenada.