In 2014, a former cab driver named Mohammed Abdus Sobhan Miah began buying apartments in an upscale building in New York City’s Jackson Heights district. Over the next five years, his portfolio came to include nine properties, worth over $4 million in total.

Miah was an unlikely real estate baron. After moving to the U.S. from Bangladesh in the 1980s, associates say he worked a series of low-paying jobs — making pizzas, serving as a drugstore clerk, and driving an unlicensed taxi.

But back in Bangladesh, where he is widely known by the nickname “Golap,” Miah was a far more prominent figure. As a long-serving member of the ruling Awami League party, he has served as a personal aide to Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina and today is a member of parliament.

Hasina, Bangladesh’s longest-ruling leader, has been a fixture of the country’s political life since the early 1980s. After serving as prime minister from 1996 to 2001, she returned to the post with overwhelming support in 2009. Since then, she has remained in power through two highly controversial elections, while her government has been accused of enforced disappearances, extrajudicial killings, muzzling the independent press, and allowing corruption to run rampant.

Miah’s New York purchases started about five years after he returned to Bangladesh to work as Hasina’s assistant in 2009. His declarations and tax records show no evidence of any U.S. income at that point, and it’s unclear how he could have accumulated millions of dollars to buy the properties from his local jobs.

It’s also unclear how Miah could have bought them with his official salary as Hasina’s aide, which amounted to the equivalent of $1,000 a month. Even if he did have millions of dollars stashed away in Bangladesh, he never applied for approval to transfer the money abroad from the central bank, as is legally required, and would not have been able to do so to buy property anyway.

“There is no legal means through which a Bangladeshi citizen can purchase property outside the country by income earned within Bangladesh,” said Iftekhar Zaman, executive director of Transparency International Bangladesh.

Reporters made repeated attempts to reach Miah by phone, text message, and email, and tried to speak to him in person, but he did not respond to questions about his properties. Hasina’s office also did not respond to emailed requests for comment.

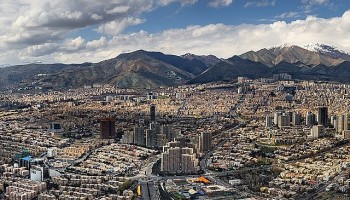

A building in Queens, New York City, where Miah owns an apartment.

Steadfast Loyalty

Miah has been involved with Hasina’s Awami League ever since he was in the party’s student wing while at university in Dhaka in the 1970s. After a stint studying in Norway, he left for New York in the mid-1980s. For the next three decades, he moved between the U.S. and Bangladesh, with the timing mirroring the rise and fall of Hasina’s political fortunes.

While in New York, Miah mobilized support for Hasina among the city’s Bangladeshi community by organizing Awami League seminars and meetings, according to two U.S.-based party leaders, who asked for anonymity out of fear of reprisals. They also said he chauffeured Hasina during her U.S. visits and assisted her son, Sajeeb Ahmed Wazed, with odd jobs when he was also living in the U.S.

After Hasina was first elected prime minister in 1996, Miah moved back to Dhaka to work as her unofficial personal assistant, the party leaders said. Five years later, Hasina lost power and Miah returned to New York, where he and his current wife worked as clerks in a Walgreens drug store, according to the two party leaders and another person who knew him at the time. At some point during his time in the U.S. he also received citizenship there.

In 2007, Hasina left Bangladesh under pressure from the military-backed regime in power at the time. When she tried to fly back to Dhaka later that year, Miah was in her entourage at London’s Heathrow Airport. Just before the Awami League swept back into power the following year, he moved back to Bangladesh and has lived there ever since.

Miah’s loyalty was rewarded in 2009 with an appointment as Hasina’s “special assistant,” a top government position that gave him extensive political influence and power, but pays just $1,000 per month. He remained in that role until 2018, when he was elected as an MP for the Madaripur 3 constituency, a district within the Dhaka region, while still a U.S. citizen — a fact that Zaman from Transparency International said should have barred him from running for office.

Miah (left, with glasses) stands next to Sheikh Hasina (center) after she is turned away from a flight at London’s Heathrow Airport in 2007.

“No foreign citizen can contest in the national election of Bangladesh. It is constitutionally barred,” he said. “If anyone conceals her/his foreign citizenship and if it is revealed afterwards his … membership in the parliament will be canceled.”

Miah only renounced his U.S. citizenship on August 15, 2019, according to official records, seven months after he was elected as a member of parliament in Bangladesh. Property records show that by then he had also acquired substantial assets in New York.

Miah’s New York Properties

Between 2014 and 2018, Miah bought five condominiums, worth roughly $2.4 million at the time, in a Jackson Heights building featuring a concierge service, an outdoor pool, and covered parking. He also bought three more apartments, worth $680,000, in nearby co-op buildings.

New York property records show that all were purchased with cash. Miah’s wife, Gulshan Ara Miah, is also listed as an owner.

In December 2019 — after Miah was elected as an MP, a role that pays a monthly salary of around $647 — he added another property in Jackson Heights: this time, a semi-detached house worth almost $1.2 million.

A semi-detached house in Jackson Heights owned by Miah.

Lack of Disclosure

The most detailed public account of Miah's finances was given in a statement of assets required for his parliamentary run in 2018.

In Bangladesh, he declared a five-story building in Dhaka’s Mirpur neighborhood, which he valued at about $40,000, and which earned about $6,000 per year in rent. He also declared about $336,000 in stocks and other investments, roughly $142,000 in bank deposits, and around $32,000 worth of gold.

His wife, Gulshan Ara Miah, disclosed a separate annual income of about $103,000 from her 50-percent ownership of Roots Communication, a telecommunication company. She also disclosed property valued at about $62,500 in Dhaka’s Uttara neighborhood, bank deposits of about $203,000, investments of about $737,000, and roughly $32,000 in gold.

Neither Miah nor his wife disclosed their New York City holdings or any other offshore assets in the declaration. Rafiqul Islam, a former Bangladesh Election Commissioner, told OCCRP that Miah’s failure to disclose his New York properties could have consequences.

“If it is proven that he lied about his wealth abroad in the [election disclosure] affidavit, he can lose his seat in the parliament — questions will be raised,” Islam said.

Candidate disclosure forms are snapshots, showing assets at the time of filing, with little or no explanation of how or when the wealth was acquired.

But even if the couple had already accumulated substantial assets by 2014, the money for the New York purchases could not have legally been transferred from Bangladesh. Such transfers are approved by the central bank on a case-by-case basis, and are typically allowed only for supporting students studying abroad or for people who need to get medical treatment — not for real estate purchases.

A building in Jackson Heights, New York City, where Miah owns five condominiums.

Mohammed Serajul Islam, the spokesman for Bangladesh’s central bank until he retired in October, said during an interview in August that someone living and working in Bangladesh would not have been allowed to move funds out of the country.

“There [is] no opportunity to purchase properties abroad, being in Bangladesh and using funds earned in Bangladesh,” he said, although he declined to comment specifically on Miah.

“No one can take funds abroad to invest into assets abroad,” he emphasized.

Bangladeshi resident citizens also have to report offshore properties or foreign income to tax authorities. But Miah’s tax returns, on file with the Bangladesh Election Commission, listed no assets in New York.

Ross Delston, a Washington-based attorney who specializes in financial crime issues, said U.S. property purchases by politically connected figures such as Miah should face higher scrutiny due to the potential for bribery and other forms of corruption.

But in practice, the system is rife with loopholes. For instance, U.S. banks make their own determinations about who constitutes so-called “politically exposed persons” and U.S. real estate agents are also not required to follow anti-money laundering procedures.

“There is a reason that plundered funds the world over find a home in the U.S.,” Delston said.