One more surprise awaited Kovsarov.

When he applied to SOCAR for any possible compensation, company officials told him that the Gum-Deniz oil field where he’d worked for so many years was now being managed by a private company based in the United Arab Emirates, and that it did not have to pay pensions.

The private company, Bahar Energy Limited (UAE), has signed an unusually lucrative deal with SOCAR. A production-sharing agreement gives it 80 percent of profits of the Gum-Deniz and Bahar oil fields, with the other 20 percent going to SOCAR.

The percentage of profit flowing to Bahar is substantially higher than average for such deals in the industry, and for at least five similar arrangements in Azerbaijan.

The unusual deal may be explained by previously hidden connections between SOCAR and Bahar officials uncovered by reporters for the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project (OCCRP) and Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, with the cooperation of the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists.

The document trail indicates that two men connected to the government agency that is supposed to be selling oil on behalf of the public were in fact using their connections to strike a deal that may have been bad for the government, while it’s not clear who ultimately benefitted.

Adem Aliyev, the father-in-law of SOCAR president Rovnag Abdullayev, and Fakhraddin Ismayilov, the head of SOCAR’s Oil & Gas Research and Design Institute, were early directors in the company that became Bahar Energy.

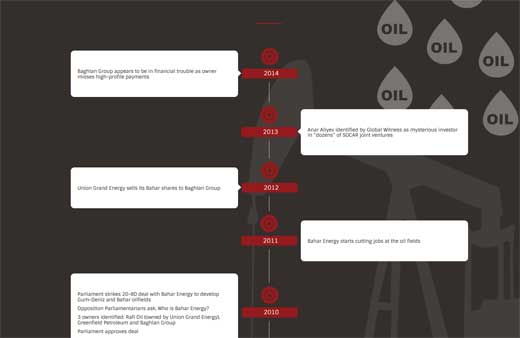

The story of what happened in the Bahar Energy deal sheds light on a series of murky transactions that have occurred in two Caspian oil fields over the past decade. According to the document trail uncovered by OCCRP/RFE, Aliyev and Ismailov sold out their interests in the operation in 2008 to Anar Aliyev, a mysterious figure linked to more than 50 other questionable public-private partnerships in Azerbaijan.

The Azeri Parliament made the lucrative deal for Bahar possible when, in 2010, it ratified the production-sharing agreement that gave Bahar 80 percent of the shares. In SOCAR’s five other offshore production sharing agreements, no private company holds more than 50 percent of shares.

A few opposition legislators could not block the the Bahar agreement, but they tried to find out who was profiting.

At an April 2010 hearing, parliamentarian Panah Huseyn asked who was behind this UAE company which would be collecting most of the profit from fields that were projected to produce 4,629 barrels of oil per day, worth about half a million US dollars a day at current prices.

Huseyn said he visited the buildings in Baku listed in the Bahar Energy records and found they also contained offices of companies linked to the Baghlan Group, which was founded and is owned by Hafiz Mammadov. Registrations records for Bahar Energy and these companies listed identical addresses.

Mammadov is best-known for his enthusiastic pursuit of football clubs. He bought sponsorship rights for the football club Atletico Madrid, which has “Azerbaijan: Land of Fire” on its jerseys. He tried and failed to buy the English football club Sheffield Wednesday. He owns the French football club Lens., and recently missed a French Football Federation deadline for a mandatory $18 million deposit into the Lens’s budget, which he blamed on Azerbaijan banks being closed on a weekend.

Mammadov is a partner with the family of Azerbaijani Transportation Minister Ziya Mammadov (no relation). When the agreement with SOCAR was signed in 2010, his Baghlan Group owned one-third of Bahar Energy. The other two-thirds were split equally between Greenfields Petroleum Corporation and Rafi Oil FZE.

Greenfields Petroleum is an oil-and-gas development company based in Houston, Texas but registered in the offshore fiscal haven of the Cayman Islands. For the first three months of 2014, Greenfields announced revenues of US$ 896,000 and net loss of US$ 3.8 million for its Bahar holdings.

Rafi Oil FZE’s ownership is more complicated, with close (and previously hidden) connections to SOCAR officials.

When it was registered in UAE in 2004, its owners were not listed. But documents located by reporters for OCCRP and RFE/RL show a company named Rafi Oil (BVI) is registered in the British Virgin Islands. Documents further show that Rafi Oil (BVI) controlled 100 percent of Rafi Oil FZE.

Two men were listed as Rafi Oil (BVI) company directors -- SOCAR’s Ismayilov and the SOCAR president’s father-in-law, Adem Aliyev.

The names of Fakhraddin Ismayilov and Adem Aliyev never surfaced in any parliamentary discussions on the Bahar Energy agreement, although watchdogs have repeatedly urged the Azeri government to require more ownership transparency of SOCAR joint ventures.

The two SOCAR insiders were no longer listed as owners when the Bahar Energy deal was signed. In 2008, Adem Aliyev and Ismayilov sold all of their shares in Rafi Oil FZE to a Singapore-registered company named Union Grand Energy PTE. In April of 2012, Union Grand Energy sold Rafi Oil’s one-third share of Bahar Energy to the Baghlan Group for US$ 150 million. So the Baghlan Group now controls two-thirds of Bahar Energy shares.

Who is Behind Union Grand Energy?

Click on image to view timeline.

Click on image to view timeline.

Union Grand’s listed owner is Anar Aliyev. He was featured in the 2013 Global Witness report “Azerbaijan Anonymous” as a mysterious partner with almost no known business background who is somehow involved in dozens of SOCAR joint ventures. After the publication of that report, Anar Aliyev released statements denying that he was a proxy for powerful people in Azerbaijan, or that he was a cousin of SOCAR president Abdullayev. Anar Aliyev has not spoken to anyone since.

Industry watchdogs aren’t convinced by Aliyev’s denials.

“Behind offshore entities are possibly hidden the names of people involved in decision-making for SOCAR,” Zohrab Ismayil, a coalition member of the Extractive Industry Transparency Initiative, told OCCRP reporters.

Vagif Aliyev, head of SOCAR Investments Department, says there is nothing wrong with private businesses registering in tax havens. “Azerbaijani citizens have the right to create businesses outside of the country. The main question is if they act within the law. None of the companies partnered with SOCAR has these issues,” he said.

Asked if it would be considered a conflict of interest for SOCAR branch director Fakhraddin Ismayilov to hide behind an offshore entity, Vagif Aliyev said: “Impossible. Fakhraddin Ismayilov doesn’t own any of those businesses.”

Vagif Aliyev says job cuts after contracts are awarded to private companies like Bahar Energy are normal. “We demand that the companies use local laborers, but these businesses require a dynamic approach, and job cuts as well as added employment are always possible.”

When Bahar Energy took control of the two fields, it nullified existing contracts and required workers to sign new short-term contracts. These allowed termination at expiration and did not address pensions. Although Azerbaijan’s labor code requires pensions--and despite worker complaints--the government has not enforced the code.

Mirvari Gahramanli, chairman of the Committee for Oil Workers Rights, says Bahar Energy began cutting jobs in 2011. “Most of those who lost their jobs are threatened and very few go to court, as they have no trust in the independence of judiciary. It is really difficult to achieve justice in the court because Bahar Energy Limited is protected by SOCAR.”

Kovsarov, who received six months’ severance pay but no pension when his job was cut, committed suicide in June. His wife is struggling to survive with two children.

Gahramanli fears this won’t be the only suicide. She says the Azeri government protects offshore companies instead of its own citizens. “Maybe these are special people whose profits are more important than the lives of oil workers,” Gahramanli said.

One of those “special people,” Baghlan Group owner Mammadov, apparently has cash flow problems beyond his football purchases.

On July 23, Greenfields Petroleum announced that it had loaned about US$ 16.5 million to Baghlan because Baghlan has not made obligatory investment payments for these partnership projects since Jan. 1, 2014. Greenfields acknowledged that it expects to have to make additional payments to cover Baghlan’s shortfalls.