One of the 2005 Orange Revolution’s major promises and the main election campaign slogan of President Viktor Yushchenko was “All criminals will be in jail.” The Ukrainian writer and political analyst Yuriy Vynnychyk said back in 2006 that Yushchenko had failed to fulfill that promise: “The promise to put the criminals in jail was broken – instead they go to the parliament.”

The ability of a man who has been, listed in police files on organized crime to win a $100,000 libel verdict in a London court against the Ukrainian paper Obozrevatel in January underscores the failure of Yushchenko’s promise.  Viktor YushchenkoRinat Akhmetov, the country’s richest man and member of parliament, won the judgment despite being mentioned in a report by the Chief department on organized crime titled, “Overview of the Most Dangerous Organized Crime Structures in Ukraine.” It listed him and hundreds of others. The report lists his name under a different spelling, Renat Leonidovich Akhmetov, and alternates its spellings of the group he is said to have headed. According to the report, Renat Akhmetov, born in 1966 in Donetsk, is listed as the leader of the “Renat’s” organized crime group. According to the document, “the group dealt with money laundering, financial fraud, and controlled a large number of both real and fictitious companies.” The group is listed as one whose activities “have been stopped,” and says further that their criminal natures “have not been confirmed.”

Viktor YushchenkoRinat Akhmetov, the country’s richest man and member of parliament, won the judgment despite being mentioned in a report by the Chief department on organized crime titled, “Overview of the Most Dangerous Organized Crime Structures in Ukraine.” It listed him and hundreds of others. The report lists his name under a different spelling, Renat Leonidovich Akhmetov, and alternates its spellings of the group he is said to have headed. According to the report, Renat Akhmetov, born in 1966 in Donetsk, is listed as the leader of the “Renat’s” organized crime group. According to the document, “the group dealt with money laundering, financial fraud, and controlled a large number of both real and fictitious companies.” The group is listed as one whose activities “have been stopped,” and says further that their criminal natures “have not been confirmed.”

Akhmetov’s lawyer, Mark MacDougall, responded by email from Washington that , “Mr. Akhmetov conducts his life and his business according to the highest standards, and will not allow false claims of this kind to go unchallenged in court.”

Many others identified in the report as major crime figures have either been killed or cloaked themselves in legal enterprise, and have never faced prosecution.

Among politicians associated with possible wrongdoing, former Minister of Transportation Mykola Rudkovsky, is facing scrutiny from normally passive prosecutors. When in office, Rudkovsky, was often at odds with Yushchenko.

For those associated with organized crime, convictions have been rare, One notable exception was Borys Savlokhov, who went by Soloha, and controlled several Kiev markets, hotels and casinos through his group, which involved 112 people and dealt in extortion, racketeering, theft and money laundering, according to a September 1999 report. The report, titled “Overview of the Most Dangerous Organized Crime Structures in Ukraine,” was made by the chief department on fighting organized crime.

In 2000, Savlokhov was sentenced to seven years in jail for extortion and hooliganism. He died there in 2004, reportedly of a heart attack.

Yet prosecutions are usually fruitless. Many have been killed or followed the example of Akhmetov or Savlokhov’s closest rival, Volodymyr Kisel. Kisel’s group included 143 people engaged in extortion, racketeering, gang robberies and car theft, according to the 1999 overview.

Kisel gave an interview to the “Ukraine Criminal” website (www.cripo.com.ua) in 2004 soon after he survived a car bomb in downtown Kiev that killed his driver and bodyguard.

Kisel, in the interview, said he was a changed man: “I am not doing anything illegal, will not do anything illegal, and don’t want to do it. I want the law enforcement agencies to delete me from all their lists and forget me altogether.” He said his main job was president of Ukraine’s Greco-Roman Wrestling Federation. As a member of the Kiev local district council, he mentioned his work on restoring churches and building a new one in his home district of the capital. “I also thought about going to study at the seminary, but so far it hasn’t worked out,” he said.

The Action in Crimea

Crimea is the only region that continuously tracks organized crime and reports on its results. In March 2008, police arrested Ruvim Aronov, a member of the Crimean Parliament, former commercial director of the local soccer club, Tavria, and one of the leaders of the Crimean organized group “Bashmaki” (The Shoes), according to police reports. The group committed about 50 murders and 8 kidnappings. Aronov himself is charged with organizing a murder, having dual (Ukrainian-Israeli) citizenship, which is illegal in Ukraine, and killing an elderly woman while he was driving a car.  Ruvim AronovIn March, the daily Kommersant reported that despite having a warrant for his arrest since August 2006, Aronov was seen in February 2007 television footage in Israel watching a soccer game with Akhmetov, Hryhoriy Surkis, president of Ukraine’s soccer federation and former Prosecutor General Svyatoslav Piskun. Currently Aronov remains in custody in Ukraine.

Ruvim AronovIn March, the daily Kommersant reported that despite having a warrant for his arrest since August 2006, Aronov was seen in February 2007 television footage in Israel watching a soccer game with Akhmetov, Hryhoriy Surkis, president of Ukraine’s soccer federation and former Prosecutor General Svyatoslav Piskun. Currently Aronov remains in custody in Ukraine.

Another case, beginning with the September 2006 arrest in Crimea of Oleksandr Melnyk, called by the police one of the leaders of the Salem” organized crime group, reportedly named after Salem Massachusetts, a sister town to the Crimean main city Simferopol, went nowhere. Oleksandr, who is suspected of organizing the killings of two people, was released by Deputy Prosecutor General Renat Kuzmin due to a lack of evidence. Melnyk immediately left the country for Russia. Kuzmin explained that Melnyk was accused by the police of organizing murders more than 10 years ago with only indirect evidence against him. The alleged murders took place in the mid-nineties.

Oleksandr Melnyk, aka Melya, born in 1971, is mentioned in the 1999 Overview as one of Salem’s leaders. He is listed as being under a search warrant. Salem is classified in the report as the most powerful OCG in Crimea.

Its main activities, according to the Overview, were “penetration in government and power structures, bribing officials and law enforcement”, which “benefited them a lot during privatization, as they were able to win the “economic war” legitimately, without “shedding too much blood.”

There was not enough evidence for the deputy prosecutor general, however. “Possibly, he is a criminal. Possibly he organized 52 murders. But if someone wants him to face the court, (this desire alone) doesn’t create evidence. Once you have the evidence, I promise you, he will be in jail,” Kuzmin said in a November 2006 interview with Kommersant.

Today, Melnyk, who returned to Ukraine late in 2006, is a member of the Crimean Parliament, where he serves on a committee for economic, budget and fiscal policies. He called any accusations against him “the rubbish of a clinical idiot.” Kuzmin, who at the time signed his release, still holds his post.

A Major Embarrassment

A series of other criminal cases involving Ukraine’s top officials close to the former government were brought throughout 2005. Among the top figures were Volodymyr Shcherban, former governor of the Sumy region, who was arrested in the United States in 2005 and deported to Ukraine, where he was charged with abuse of office, extortion, financial fraud and other crimes. In 2007 the prosecutor general announced a finding of no criminality in Shcherban’s actions.

Yevhen Kushnariov, governor of the Kharkiv region, was arrested in 2005 on charges of separatism – calling for the autonomy of eastern regions of Ukraine – to which the charges of abuse of office and embezzlement of funds were added. He was released on bail, and the case against him was closed due to lack of evidence. Kushariov died in January 2007 in an apparent hunting accident.

The list of failed prosecutions includes that of Borys Kolesnikov, head of the Donetsk region council, who was arrested in 2005 by the organized crime police unit on charges of extortion and murder threats. He later was also charged with separatism. The prosecutor general closed his case in 2006, finding no crimes were committed.  Yulia TymoshenkoThen, last year Kolesnikov was given a state award “For Service” by Yushchenko, who only two years before had attempted to charge this close ally of Akhmetov with extortion.

Yulia TymoshenkoThen, last year Kolesnikov was given a state award “For Service” by Yushchenko, who only two years before had attempted to charge this close ally of Akhmetov with extortion.

“Probably, the President has forgotten that in 2004 he personally promised to put criminals in jail” – says a statement from Prime Minister’s Yulia Tymoshenko political party. “It is obvious to anyone that now this slogan has been modified to “All criminals will be given awards”. The statement adds that such practice of giving state awards to people with questionable reputation is very offensive to the people, as the awards should not be given for “corruption, shady deals and belonging to criminal and oligarch groups.”

According to Ukrainian political analyst Volodymyr Malenkovych, Yushchenko, officials of his secretariat, and Rinat Akhmetov and his people make up one group opposing popular populist Tymoshenko, who is likely to win the next presidential elections in 2009. As of mid-September the coalition between Tymoshenko and Yushenko broke down, and both are now competing for the union with the Party of Regions, largely under the influence of Akhmetov, to avoid new parliamentary elections, with Tymoshenko being their likeliest ally.

Yet members of parliament and one of the country’s prominent intellectuals, Vyacheslav Briukhovetsky, see no conspiracy behind the lack of legal action taken against persons labeled as “criminals” during the Orange revolution. Instead, he blames it on the low professionalism of law-enforcers, which “set up the President.”

“[Shcherban, Kolesnikov and other representatives of the former government] were detained without the necessary basis of proof… Kolesnikov’s case was on TV every day. If [the police make it that] public, you’ve got to be sure you can complete the investigation… As a result – no one is in jail, and no one’s guilt [is] proven,” said Briukhovetsky in his 2005 interview with Ukraina Moloda.

A Socialist in a $500,000 sports car

The one case against an official that security service officers think may succeed involves former Minister of Transportation Mykola Rudkovsky. During his tenure as a minister, Rudkovsky was known for his criticism of Yushchenko as well as for his exuberant life-style. He was often seen driving a $500,000 Aston Martin despite being a member of the Socialist Party.

Shortly after his Socialist Party lost the elections and its seats in Parliament, causing Rudkovsky to lose his post, the Security Service of Ukraine launched a criminal case against him for embezzlement of funds in especially large amounts and abuse of office. Specifically, Rudkovsky was charged with spending nearly $200,000 in state funds for chartered flights to Paris and Brussels. Rudkovsky is also charged with taking an airline trip with his brother around the world via Vienna, Tokyo, Honolulu, San Francisco and Munich and billing the $20,000 cost to a state transportation company.

Currently, he is free on bail during his court trial. According to prosecutor Oleksandr Lubnin, if convicted he faces up to 12 years in jail.

“We are sure that his punishment will be imminent,” said Maryna Ostapenko, spokesperson of the Security Service of Ukraine.

Postscript: Land Matters

At a time when more than 80 percent of state property has already been privatized and just a few lucrative parcels have yet to pass into private hands, land that still officially cannot be sold becomes an enormous asset. People in charge of renting public land – the village council heads – often find it hard to resist the temptation to abuse their power. Because a majority of them lack the political connections to protect them from prosecution, they often get caught.

Ukraine’s Ministry of Internal Affairs in June compiled a list of bribes exposed this year, half of which were related to land distribution. Among the top 10 bribes that range from $250,000 to $5.37 million, nine of them were given to village and district council officials or people who have some control of the land.

At the top of the list is the village council of the Crimean village of Partenit Mykola Konev, where resort construction was booming, which was charged with receiving a $5.37 million bribe for promising to allocate 17 hectares of village land worth approximately $35 million to an unnamed Kiev businessman. He remains in jail during the course of investigation. This is considered an all time record for a bribe.

No one accused in the 84 bribery cases exposed this year by the police has been convicted to date.

**********************

A Man Conscious of Image

In January 2007, the Ukrainian Web-based Obozrevatel newspaper shocked the nation with its bold attempt to investigate the early years of the country’s richest man, Rinat Akhmetov, whose wealth is estimated by Korrespondent magazine in Ukraine at $31.1 billion. Forbes Magazine estimated that his 2008 net worth was $7.3 billion.

The results of their investigation, published in a five-part series of articles, reminded readers of an adventure story set in the harsh conditions of a suburb called Oktyabrsky in the Eastern Ukrainian city of Donetsk. People who knew Akhmetov from his high school years and after shared their memories of him.  Rinat AkhmetovThe chief editor of Obozrevatel, Oleh Medvedev, who now is a political advisor to Prime Minister Yulia Tymoshenko, back then joked that he was often accused of being paid by Akhmetov to create an image of a rough but just man with a controversial past who had to learn to adapt to the cruel conditions of his youth in order to survive.

Rinat AkhmetovThe chief editor of Obozrevatel, Oleh Medvedev, who now is a political advisor to Prime Minister Yulia Tymoshenko, back then joked that he was often accused of being paid by Akhmetov to create an image of a rough but just man with a controversial past who had to learn to adapt to the cruel conditions of his youth in order to survive.

So it was a bolt from the blue in March that same year when he was notified about a lawsuit against his publication filed by Akhmetov’s U.S. and British lawyers in London’s High Court of Justice.

In January 2008, news of the verdict showed Akhmetov the winner in the London court; in June, the court ordered Oleh Medvedev, another Obozrevatel editor and Tetyana Chornovil, the journalist who wrote the series to pay $100,000 in damages and costs to compensate Akhmetov for damage to his reputation. Akhmetov said he planned to give the award to charity.

The ruling has left the public unlikely to ever learn exactly how this businessmen and member of Ukraine’s parliament got started. The London ruling could discourage Ukrainian media from doing any further investigative work on Akhmetov, who continues to shun media attention, except when talking about soccer and charity.

“As you know very well, Mr Akhmetov has done a lot of work to protect his good name from false accusations, which might hurt the reputation of his family and business. As the result of it, many publications in Ukraine and other European countries had published retractions and apologies… [and] admitted that their claims are false. We think that these facts speak for themselves”, said his Washington D.C. – based lawyer Mark MacDougall.

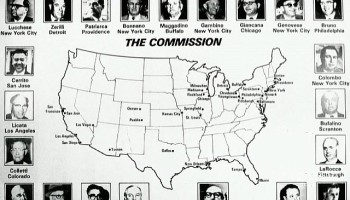

Akhmetov’s name appears with hundreds of others in a September 1999 report by the chief department on fighting organized crime titled, “Overview of the Most Dangerous Organized Crime Structures in Ukraine.” Although the report has been kept secret, a copy was obtained for this story.

Very few of those named on the list have been arrested, much less prosecuted.

Akhmetov’s Closet

When asked about what he did in the years after he graduated from school in 1983, Akhmetov usually becomes elusive, saying only he learned to work at some unspecified jobs by learning from others, according to an article in Obozrevatel. His official work history starts 12 years later in 1995, when he is listed as among the founders of the Donetsk-based Dongorbank. He graduated from the university in 2001, majoring in marketing.

The rest of the story, as told by Akhmetov’s former neighbors and childhood friends in the Obozrevatel articles, is about a neighborhood with “roads where dirt never dries up, where guys were all cool,” and where nowadays you can hardly meet anyone who is between 40 and 50 years old, as they all have either “left town, died from alcohol or drug abuse, or simply got killed.” Most of Akhmetov’s closest friends now lie buried in cemeteries. Akhmetov will turn 42 in September.

The most controversial parts of the series dealt with Akhmetov’s alleged participation in torturing and killing an underground businessman in 1986. There the article uses at is source the book “Donetsk Mafia,” which quoted an opposition newspaper publication. According to Medvedev, this was one of the major reasons for Akhmetov’s libel suit.

Serhiy Kuzin, an author of “Donetsk Mafia,” published in 2006, claims in his book that until 2004 the police in Donetsk kept a file on Akhmetov, which has “disappeared.” The head of the local police, Volodymyr Malyshev, who resigned in 2004, was appointed the next year as head of the System Capital Management holding’s security service, the majority of which is controlled by Akhmetov. According to Kuzin, the file was either destroyed or is held by Akhmetov. Malyshev is now a member of Parliament on the committee controlling law enforcement in Ukraine.