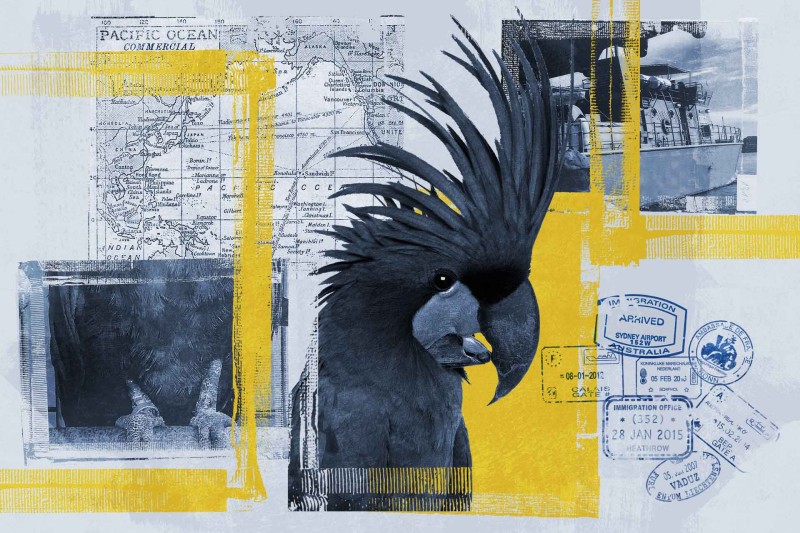

Stanislavas Huzhiavichus had two palm cockatoos and 12 birds of paradise in the trunk of his rental Audi A4, and a gut feeling that something wasn't right.

Everything was fine with the birds — he had made sure they were fed and watered, and the cockatoos' black headfeathers were long and lustrous — but the parking lot where he was about to hand them over in exchange for a briefcase full of cash was a little too quiet.

Usually, the wildlife smuggler met customers in the relative safety of their homes. But this time the buyer, a Swede, had insisted on doing the handover in a public place, at a strip mall about 45 minutes’ drive outside Vienna. Still, Huzhiavichus ignored his misgivings. This was going to be a big deal: The birds were going to be swapped for 133,000 euros ($161,000) in cash.

Then “all hell broke loose,” he recalled.

Commandos from the Austrian Interior Ministry’s elite Task Force Cobra stormed out of a white van, blocking the exits of the parking lot. Huzhiavichus made a move to run, but was quickly brought down by an officer. The operation was over so fast that the afternoon shoppers at the nearby garden center barely noticed the commotion.

Police seized Huzhiavichus’s laptop and phones that day in April 2018, their contents providing a rare glimpse into a global wildlife trafficking ring that spanned three continents, smuggling exotic birds from South America and Asia into Europe. Regular customers included wildlife conservation centers, a breeder of Arabian horses, and wealthy bird aficionados across Europe.

“Increasingly, our analysis found that our perpetrator was part of a large-scale smuggling ring,” said Andreas Pöchhacker, a veteran Austrian customs agent who led the case. “We were surprised, but we quickly came to understand how the whole thing was organized.”

Huzhiavichus spent four months in an Austrian jail, but was released after a not-guilty verdict that was later ruled to have been issued in error. The court sought his re-arrest, but he had already packed up and left for his native Ukraine. Since then, a second case launched against Huzhiavichus in Austria has found him guilty in absentia of racketeering.

But OCCRP managed to track Huzhiavichus to his home in Ukraine, where he revealed more about the inner workings of the multi-million-dollar wildlife trafficking ring behind the Austrian bird bust.

Messages sent between the shadowy kingpin who controlled the smugglers and a high-level co-conspirator confirm Huzhiavichus’ account of a network that took advantage of CITES — a system created to govern the trade in rare species — to traffic some of the world’s most-threatened birds across the globe.

“We deliver from Chile, we want to bring from Venezuela. We work in Ecuador, Peru, Colombia, Asia, Slovakia, Ukraine, Croatia,” one message reads.

In another, a member of the ring tells a potential customer that ”my people are in Australia now and they can bring eggs and birds from there."

“No one checks his plane, because he has diplomatic status. But the plane is registered in Panama. … it is not a problem for him, so if you want to deliver birds to any country, he will deliver."

OCCRP was unable to confirm if this was more than just boasting. But text messages between the smugglers, as well as photographs found by Austrian police on Huzhiavichus’s cell phone, show the group flew birds from Asia to Europe on commercial planes. Along the way they bribed an array of officials and border police.

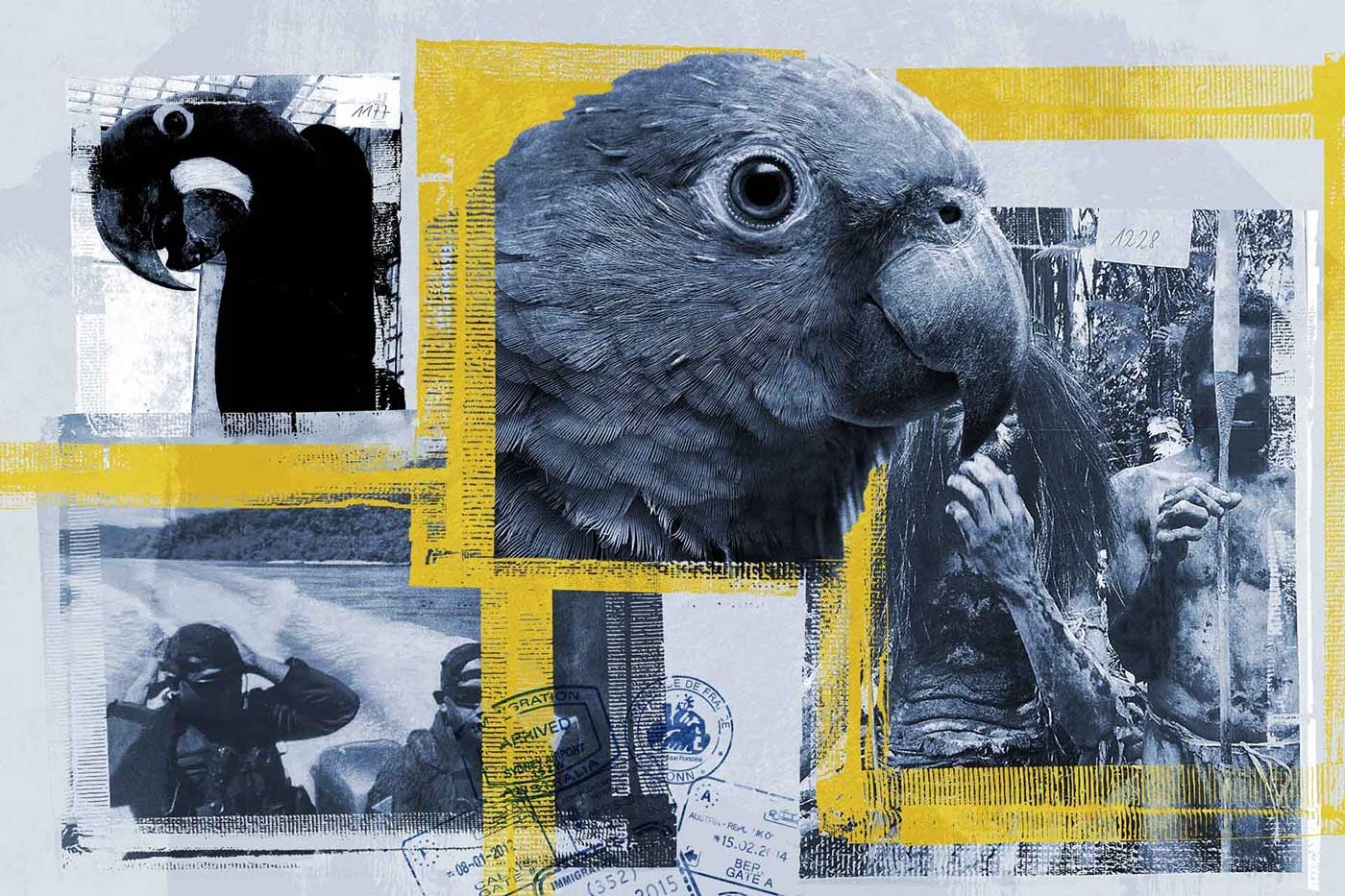

Many of the birds died en route from their rainforest homes, where they were often caught in glue traps on tree branches and their legs and wings broken as they were removed, before being sold to the network’s couriers. Crammed into cages or boxes for the journey to the traffickers’ basement processing facility in Kyiv, those that did survive shipment often did not last long.

But this didn’t matter to the smugglers, Huzhiavichus told reporters, because the profit margin on trafficked birds was so high. With some of the most sought-after specimens, they could make money even if just one or two birds survived a trip.

Austrian authorities found evidence of at least five couriers who delivered parrots and other rare birds across Europe for Huzhiavichus’ boss. Others traveled farther afield, visiting sites where birds were sourced in Papua New Guinea and other locations. Austrian officials estimated the ring could have made around 30 million euros per year ($36 million at the time).

“These disturbing findings remind us that wildlife trafficking affects every continent, and it is happening right here in Europe,” said John Scanlon, chair of the Global Initiative to End Wildlife Crime. “Far too often we see low penalties and a lack of enforcement, making wildlife crime a dangerously low-risk and high-reward activity.”

The Bird Man of Kropyvnytskyi

No crime is more rewarding than trafficking wildlife, according to Huzhiavichus, now 30, who worked as a veterinarian before falling in with the bird smugglers.

“Smugglers of narcotics and weapons, they don’t know about the better business — of course it’s the business with animals,” he said.

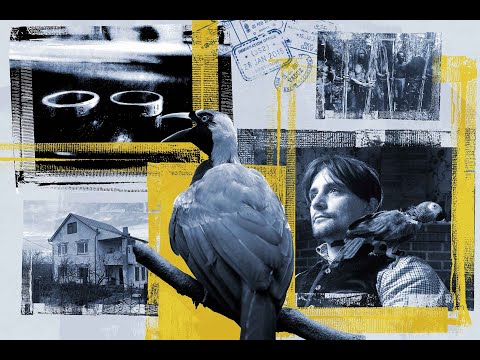

After spending four months in an Austrian jail in 2018, Huzhiavichus returned to Ukraine, where he swears he is officially retired from the bird-smuggling business. Today, he runs a small shelter for birds out of his family’s house in Kropyvnytskyi, a small city in central Ukraine where Soviet Ladas and luxury SUVs share the streets. When Russia invaded earlier this year, he stayed to take care of the birds, despite artillery and air attacks in the area.

Huzhiavichus’s family home in Kropyvnytskyi, Ukraine.

Over hours of interviews in Kyiv and his hometown before the war began, Huzhiavichus explained the economics of bird smuggling and the role he played. As he spoke, his African gray parrot, Syoma, perched on his shoulder, occasionally leaning in to nuzzle him.

Stanislavas “Stas” Huzhiavichus at home in Ukraine.

Each trip to deliver birds, Huzhiavichus said, usually earned the group around 50,000 euros, though the sum could be as high as 140,000 euros. Birds of paradise could sell for between 25,000 and 30,000 euros ($31,000 to $37,000 at the time), palm cockatoos for 20,000 euros ($25,000) and Amazon parrots for almost 10,000 euros ($12,400). And the smugglers had very few expenses.

“This business really does not require anything,” he said. “You need some connection with customs … and a little money, a few thousand euros, and that’s all — you have the start-up capital for this.”

In the Austrian jail, gang members and drug traffickers at first derided Huzhiavichus as the “bird catcher.” But he said their mockery turned to amazement when he explained how profitable the trafficking of rare birds could be. Some inmates even proposed they go into business together, forming a new smuggling ring with Huzhiavichus at the helm.

“If you are unscrupulous, you can just go to Indonesia, buy that palm cockatoo for $500 and sell it in Europe for $16,000. It will pay off like 34 times for one bird. And if you bring 10 birds… This is a very simple way to easily and quickly make a lot of money — astronomical money.”

Huzhiavichus said he always dreamed of becoming a veterinarian, even though the job isn’t well-paid or particularly respected in Ukraine.

In 2017, two years after he graduated from the National University of Life and Environmental Sciences of Ukraine, he replied to a job advertisement that promised work with exotic animals. That evening a man calling himself “Konstantin Nikolaevich” called for an interview, asking about the birds Huzhiavichus had nursed back to health in his childhood, his studies, and his internship at Kyiv zoo.

He was hired on the spot. Konstantin told Huzhiavichus his new job was to keep several dozen birds alive. Huzhiavichus soon discovered they were kept in a windowless basement storage facility below a shopping center on the outskirts of Kyiv, where many of them arrived in terrible condition with broken wings and missing feathers.

Huzhiavichus describes the facility as a terrifying place, unventilated and lit by fluorescent lights, with a lingering stench of mold and feces in the air. In a dozen rooms, cages were sometimes stacked from floor to ceiling, so tightly packed that the birds were in constant distress. Workers called it “Arkham,” Huzhiavichus said, after the grim mental asylum in the Batman comics.

The shopping center on the outskirts of Kyiv where smuggled birds were kept in a basement.

After seeing the conditions, the young veterinarian had reservations about the job, but Konstantin offered more than double what his university classmates were making, plus a rent-free apartment in one of Kyiv’s upscale neighborhoods. Still, Huzhiavichus said it took him a month to fully understand that this was not, in fact, a breeding center, but a trafficking facility. On average, around a third of the animals died. Sometimes, it was the entire shipment.

The traffickers dumped the carcasses of the birds in the trash, and sent the sickly, “almost dead” survivors to buyers in the European Union. “Without treatment, these birds would die in two months,” Huzhiavichus said.

He said he convinced his boss to let him install ventilation and start feeding the birds a more varied diet. Survival rates improved and within a few months the head vet was fired and the boss, Konstantin, put Huzhiavichus in charge.

Huzhiavichus described Konstantin as a cipher. Nobody at the bird-processing facility ever saw him face-to-face. He used SIM cards from China, Russia, Germany, Switzerland, Ukraine, and Papua New Guinea and was an ever-present figure behind the scenes of Arkham, watching staff through dozens of surveillance cameras and ordering them back to work if he caught them idling.

Kostantin revealed little about himself, though he boasted of having high-profile political connections, and claimed he had been a major in the Ukrainian security services.” (The Security Service of Ukraine did not respond to questions.)

Konstantin went by several aliases, according to Huzhiavichus, but his preferred identity was “Alex Adamec,” supposedly a Slovakian man. The name “Alex Adamec” appears on so many documents unearthed by Austrian police — including sales agreements and fake veterinary certificates — that customs authorities opened an investigation into him, until Slovakian police informed them that the man did not exist.

Phone calls to numbers used by Konstantin went unanswered. Ukraine’s Ministry of Environment did not respond to specific questions about the bird smuggling ring.

From the Rainforest to the Steppe

Throughout the tropical island nations of Indonesia and Papua New Guinea, another young Ukrainian man, Maksym, was tasked with sourcing the birds.

At these markets, anything can be bought for the right price. “If I find a unicorn for sale in a market in Indonesia, I would not be surprised,” said Chris Shepherd, the executive director of Monitor Conservation Research Society, who has been investigating bird smugglers for more than two decades.

Huzhiavichus claimed that Maksym also poached birds in the jungle, aided by corrupt law enforcement. When Austrian police confiscated Huzhiavichus’ phones and a laptop, they retrieved photos Maksym had sent, showing him with officers from the Royal Papua New Guinea Constabulary, some armed and wearing tactical gear, and members of an indigenous group.

The long transports to Europe often didn’t go well. About six months after he started working at “Arkham,” Huzhiavichus opened a shipment of small green parrots, each no larger than a mobile phone. In three plywood boxes, the smugglers had stuffed a total of 300 birds. Only 17 had survived the journey.

When Huzhiavichus confronted Konstantin, he said the boss offered to make him a courier, which would give him more direct responsibility for the birds’ well-being — and pay 1,000 euros ($1,200) per trip, all expenses paid. Huzhiavichus’s career as a wildlife smuggler had officially begun.

The European Union generously supports anti-wildlife trafficking efforts abroad, but experts say it’s breathtakingly easy to smuggle wild animals within the bloc. Traffickers like Huzhiavichus are aided by the lack of border controls inside the 26-country Schengen Zone, as well as a lack of attention to enforcement. In his new role as a courier, Huzhiavichus said he smuggled more than 1,000 rare birds across Europe with ease. The fact that he was a dual citizen who also held a Lithuanian passport made it especially simple for him.

He said the smugglers’ favored method was bribing train conductors in Kyiv to lock the birds in compartments and smuggle them into the EU. Then he would pick them up at major train stations in cities like Budapest, from where he could drive anywhere within the Schengen Zone without fearing inspections. In his journal, he kept a meticulous record of the animals he sold, plus detailed menu plans for what they liked to eat.

Riding in Cars With Birds

A second route involved payoffs to corrupt border officials in Uzhgorod or Vysne Nemecke, a border crossing between Ukraine and Slovakia.

On his first assignment, in September 2017, he picked up four birds of paradise in Kosice, Slovakia, loaded them into a rental car with an EU license plate, and crossed the continent before taking the Channel Tunnel to the U.K.

“Most of the time, they are just waving you straight through,” said Alan Roberts, investigative support officer with the U.K. National Wildlife Crime Unit. Some 60,000 people use the tunnel on average per day. “It’d have been very easy,” to smuggle birds under the Channel, he added.

The few times in his career that Huzhiavichus was stopped, he presented a handful of permits. None of them applied to the birds he was transporting, but they satisfied the border officials.

”He’s very forthcoming. He says, ’Here are the birds, here are the documents, and please allow me to continue.”

Andreas Pöchhacker

Austrian customs official

“He’s very forthcoming,” Pöchhacker, the Austrian customs official, said of Huzhiavichus.

“He says, ‘Here are the birds, here are the documents, and please allow me to continue my journey, because these are live animals, they are very expensive, and I have to deliver them.’”

Jumping Through Loopholes

Successful criminals often hide in plain sight. In the case of wildlife traffickers, they operate in tandem with a legitimate trade in protected species that counts over a million transactions per year.

The industry is governed by the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Flora and Fauna, commonly known as CITES, which regulates how over 38,000 otherwise protected species of animals and plants can be traded. These loopholes are often exploited by traffickers, experts say.

“There are many ways in which the CITES permits system gets abused,” said Crawford Allan, wildlife crime lead at World Wildlife Fund.

Each CITES-listed animal crossing an international border needs to have a unique CITES permit, which is presented to officials just like a passport for humans. But the documents are easy to forge or falsify. Allan said there have been many cases of obtaining them through fraud or bribery, and it’s rare for a border official to be able to spot the difference between a real and a fake permit — or between one bird and another.

Fake IDS

This means that once a trafficker has obtained a permit, “you can use one and the same over and over again,” Huzhiavichus said. In some cases, he said he used the same paperwork to smuggle 20 different poached birds.

One permit found by Austrian police in his possession, for a palm cockatoo, had been registered by a wildlife park in western Germany and issued by Germany’s Federal Agency for Nature Conservation (BfN). (An owner of the park said they had imported the parrot for another breeder and called the abuse of the document a “disgrace.”)

Huzhiavichus said the ring of smugglers he worked for also skirted CITES rules using tiny metal rings with serial numbers that are normally fitted on juvenile captive-bred birds, which can be legally bought and sold. Since these rings are too small to be placed on adult birds, this system has long been considered a foolproof way to make sure that wild birds can’t be traded.

But Huzhiavichus said his group found a way around this, using a special tool to put a larger ring on a grown bird, then squeeze it tighter, so it looked genuine.

Captive birds are also supposed to be fitted with microchips carrying unique identifying information, but some of the buyers got around this by taking the chips out of a dead bird and inserting them into the new one.

According to WhatsApp conversations between Konstantin and his customers, the buyers understood they would pay an additional fee of 5,000 euros ($5,400) for a bird “with papers.” In one message, “Alex Adamec” speaks about flying birds from Peru to Madrid, where they will be given “original documents” with which they will arrive in Ukraine.

The British Bird Collector

On the day of his first courier trip in September 2017, Huzhiavichus arrived at a nondescript office building in London with four birds of paradise. He handed them over to a friend of Todd Dalton, who had purchased the animals for 16,000 euros for his estate in a secluded corner of Cornwall. Messages and documents in the Austrian court files show that Dalton was apparently one of the traffickers’ regular customers.

Dalton — who did not respond to multiple emails seeking comment and declined a request to be interviewed for this story — has long had a penchant for rare animals. In 2002, his restaurant serving yak, zebra, and sweet-and-sour crocodile was written up in the Guardian. He also kept clouded leopards in his backyard in South London, earning him minor notoriety as the “Leopard Man of Peckham.” Around 2006, he opened the Rare Species Conservation Centre, a zoo in Sandwich, near England’s south coast.

“If we can get people to visit us and become engaged with these rare animals by meeting them in Sandwich, these species might have a better chance of survival in the wild,” Dalton told a local newspaper at the time.

In 2015, the Rare Species Conservation Centre closed due to a lack of funds. Around the same time, Dalton moved his animals onto an estate in Cornwall. High fences, walls of bamboo, and surveillance cameras surround the property, which is currently listed for 1.57 million British pounds (over $1.9 million). There are no signs, and it’s not open to the public. But on Instagram, Dalton promotes what he calls his “Leopard and Goat Farm,” showing off giant flying squirrels, Sunda leopard cats, bush dogs, and a pair of cassowaries.

Dalton’s estate in Cornwall.

Over Christmas in 2017, rains washed out the soil underneath one of the fences, creating a hole just large enough for a leopard to slip through. For six days, it prowled the surrounding hills, attacking several sheep before being caught.

Court documents filed by Austrian prosecutors show that at least some of Dalton’s birds appear to have been trafficked via Konstantin’s network. In a series of text messages, “Marko Vukovic” discusses sales of birds of paradise (“bop”) with Todd Dalton. (Huzhiavichus told reporters that Vukovic was an alias used by his boss, but that he also had access to a WhatsApp account in Vukovic’s name, and used it occasionally.)

The court files also include a seemingly fake January 2018 veterinary health certificate for keel-billed toucans and chestnut-mandibled toucans — both species found in South America — bearing Dalton’s name and address in Cornwall, as well as twelve-wired birds of paradise, which lists Marko Vukovic as consignor and Todd Dalton as the consignee.

A sales agreement between “Alex Adamec,” Huzhiavichus, and Dalton from April 2018 also lists Dalton as the buyer of two palm cockatoos and a red bird of paradise. In August that year, the Leopard and Goat Farm posted an image of a bird of paradise to its Instagram page. It was deleted after a reporter inquired about it.

OCCRP has not seen evidence that Dalton knew the birds he purchased were trafficked. But experts like Shepherd of the Monitor Conservation Research Society say there are vanishingly few legal ways to buy rare species like birds of paradise, which are native to Indonesia, Papua New Guinea, and Australia.

They would have to be bred in captivity for their trade to be legal, but this is “extremely difficult to achieve” due to the birds’ complex mating rituals and solitary nesting practices, according to a report co-authored by Shepherd for the anti-wildlife trafficking NGO Traffic, which noted that “only a few specialized facilities have managed it successfully.”

“Any bird of paradise in private hands should be investigated,” Shepherd said.

For the wealthy and powerful, exotic species are a status symbol, a pricey hobby, sometimes an obsession. Some rare-animal aficionados register their collections as zoos, which comes with tax breaks and easier access to rare, CITES-listed species. The U.K. alone has more than 300 licensed zoos, but only about 100 are members of professional associations that require them to be regularly open to the public.

As for the others, like the Leopard and Goat Farm, there may be little to no indication from the outside that they house exotic species. And there’s no way to know how many species are kept at such centers, or in private hands in general, said Roberts of the U.K.’s National Wildlife Crime Unit. Unless they are dangerous, there is no requirement to register them, or even say when they are given away again.

And although Dalton is known to the Wildlife Crime Unit as a regular trader, Roberts said that they would need to be presented with evidence of wrongdoing to justify an investigation.

”We’re not allowed to go on what we might call a fishing trip. We’d need some evidence that someone’s dodgy,” he said.

Driving Birds Around Europe

After his first successful courier assignment, Huzhiavichus said Konstantin began to trust him and the assignments came rolling in. He took palm cockatoos to an architect in Bratislava and sold long-tailed parakeets to a woman in the Netherlands. Once, he set up shop at a major international bird show in Reggio Emilia, Italy, where parrot aficionados have been flocking for more than eight decades. There, he sold less obviously trafficked birds — ones that weren’t conspicuously rare — and said he took in about 150,000 euros in one day.

One of the traffickers’ best customers, he said, was the Association for the Conservation of Threatened Parrots (ACTP) in Germany, which has been accused in a string of media reports over the past few years of trading rare birds under the guise of conservation.

ACTP’s head, Martin Guth, grew up in East Germany, and in previous interviews has spoken of how collecting birds provided a rare sliver of color in his drab early life. In the late 1980s he fled to West Germany and worked in a pet shop.

He also continued expanding his rare bird collection, at one point owning more than 500 of the world’s rarest parrots, according to Audubon magazine. Some were purchased from private collectors; in other cases, nations like the Caribbean island of Dominica allowed their rare birds to be sent to Germany, where Guth promised to breed them as “safety net populations,” although this sparked controversy among conservationists. Guth has also acquired the world’s last Spix Macaws, a species declared extinct in the wild, and is currently trying to reintroduce them to their native Brazil.

ACTP’S breeding facility outside Berlin.

Though Australia stipulated that the parrots were intended for exhibition purposes only, the Guardian’s 2018 investigation found that glossy black cockatoos imported from Australia were then offered for sale by ACTP in Germany. The Guardian also reported that a seller identifying himself as part of ACTP had offered rare Australian purple-crowned lorikeets for sale online.

Through its lawyers, ACTP called this allegation “completely untrue” and noted that an investigation by the public prosecutor in Frankfurt Oder had found no evidence a crime had been committed in Germany. The Federal Agency for Nature Conservation (known by the German abbreviation BfN) told OCCRP that Australia was responsible for issuing export permits for its birds, and that the BfN’s role was limited to checking whether the conditions for import had been met.

Although breeding parrots is an expensive business, requiring specialized food and veterinary care, ACTP does not publicly disclose financial information, making it difficult to know how it funds its operations. The BfN said it wasn’t empowered to investigate the finances of organizations like ACTP.

"From time to time there have been accusations that one doesn’t know exactly where the money is coming from and how it is being used there, but these are questions that we as a nature conservation authority certainly can't examine," said Michael Müller-Boge, senior enforcement officer for CITES at the agency.

Guth declined to show reporters ACTP’s collection of birds, which are housed in a Berlin breeding facility registered as a zoo that reportedly cost $3.8 million to build. He confirmed he bought palm cockatoos from “Marko Vukovic,” but claimed he was suspicious of the trader, who didn’t provide a guarantee of origin required for EU sales. ACTP subsequently denied that he had provided this confirmation.

Guth said he contacted the BfN as a safeguard and had them check that there was “nothing incriminating” on their files about “Marko Vukovic.” Guth referred all other questions to the BfN.

“If Mr. Guth says that, that might very well be the case,” Müller-Boge said in a phone interview, adding that he’d need to elaborate on details in writing. In a subsequent email, the BfN said that it could not verify Guth’s claims, and that it was not responsible for the wildlife trade within the EU.

“Also, we cannot confirm that ACTP acquired such birds in the EU, as the obligation to report is not within the area of responsibility of the BfN,” it added.

The smuggler’s claims that ACTP was a customer appear to be corroborated by messages found in the Austrian court documents, sent by the non-existent “Alex Adamec” to a third party.

“[We have] a deal with ACTP on Tuesday, they bring us 3 gang gang [cockatoos] and we need to pay them,” Adamec wrote in a January 2018 text message, adding that he would pay ACTP 42,000 euros ($50,000).

“That bird that you saw yesterday is going to ACTP,” he wrote of an unidentified animal a few weeks later.

Asked for comment, lawyers for ACTP noted that the organization was in full compliance with the law and was “taking direct action on the ground to protect endangered parrot species from illegal trade and to preserve habitats from human impact.”

“Our client [Guth] has no information about any wildlife trafficking/smuggling rings…and their modus operandi,” they said.

ACTP’s lawyers said they could not respond in detail to claims that Guth had dealt with Huzhiavichus’ group of smugglers because reporters had not provided the name of the group. (Many organized crime groups do not have names.)

They confirmed that Guth did discuss the purchase of birds with a person known as “Marko Vukovic” in 2018, but said he never went through with the sale because a bird tested positive for herpes. They also reiterated his statement that he had contacted authorities to check Vukovic’s background. “At the time, our client had no knowledge that there were or could be indications of questionable or illegal activities in connection with this person,” they wrote.

The Last Trip

In April 2018, Huzhivichus drove south from Germany to Austria, where Johann Zillinger, a convicted wildlife smuggler, had set him up with a buyer who turned out to be an undercover cop.

Huzhivichus was arrested the same day, outside the garden center. The legal case against him was split in two — one for the rare palm cockatoos he was bootlegging, and one for the less rare birds of paradise. In the cockatoo case, he was acquitted on a technicality in September 2018, but prosecutors appealed the verdict, saying the judge had misunderstood Austrian laws on CITES protection.

“Based on the wrong verdict the perpetrator was released from arrest,” said Pöchhacker, the customs official who led the case. “And then the wrong judgment [was] overturned but then he wasn’t there anymore.”

He said the second case, involving birds of paradise, resulted in a conviction against Huzhivichus for racketeering, but by then the erstwhile smuggler was long gone. In theory, he’s still wanted by Austrian authorities, but in practice they don’t have the resources to pursue him in Ukraine.

Since returning home, Huzhivichus said he has devoted himself to veterinary work, tending to injured birds and mistreated parrots at his own makeshift shelter. Like his wealthy clients in Europe, Huzhivichus too is a bird aficionado with a bug for collecting.

Cockatiels in the aviary.

He said he believes his former colleagues continued to move endangered birds into Europe, but he hasn’t heard from “Konstantin” since shortly after his release in 2018.

After Russia invaded Ukraine on February 24 and began shelling Kyiv, Huzhiavichus said he reached out to one of Konstantin’s associates to ask if they needed help rescuing the birds left in the basement. He was told they were fine.

As for Huzhiavichus, he intends to stay on his farm. His shelter’s current inhabitants run the gamut from protected African grey parrots to ordinary pet budgies and cockatiels left behind by Ukrainians who fled the country after the Russian invasion. There’s also a stork with a broken wing he calls Boris. One night during reporters’ visit to his home, he freed a boy’s pet parrot from a toy bell that had become stuck on its beak.

An aviary where Huzhivichus keeps his birds.

Later this year, as air raid sirens rang through Kropyvnytskyi, Huzhiavichus kept calmly feeding bananas and nuts to his birds. All of them are kept in neat aviaries behind his parents’ house, ready to be moved to a bomb shelter within two minutes “in case anything is to happen,” he told reporters.

For the most part, though, bird owners called Huzhiavichus for advice on how to flee with their animals. They worried that it would be hard to get them across the EU border.

It wouldn’t be, he reassured them.

Elena Loginova (OCCRP/Slidstvo.Info), Philip Oltermann (The Guardian), and Lisa Cox (The Guardian) contributed reporting. Olena LaFoy and Nick Flynt contributed translation.

Editor's Note: This story was edited to conform to German privacy laws.