Cyprus’s “golden passport” program is considered a corrupt free-for-all that gave kleptocrats, oligarchs, and criminals access to European citizenship.

From Putin crony Oleg Deripaska to fugitive Malaysian fraudster Jho Low of the infamous 1MDB scandal, Cyprus’s willingness to sell citizenship to unsavory people has been a black eye for the European Union as it ramps up anti-corruption efforts.

Cyprus stopped taking new applications last October following an Al Jazeera news undercover sting that caught politicians offering to help get a passport for a fictitious criminal from China. The EU has also moved to hold Cyprus accountable for its investor citizenship scheme through an “infringement procedure” that could potentially lead to financial penalties imposed by its Court of Justice.

While the Mediterranean nation has promised reforms, questions remain about corruption among its political class.

Some public officials and Cypriot media have pointed to the relationship between President Nicos Anastasiades –– whose family law firm was deeply involved in procuring golden passports for clients –– and Saudi businessman Abdulrahman bin Khalid bin Mahfouz, whose receipt of citizenship has been questioned by the Auditor General of Cyprus.

The Auditor General hasn’t accused anyone of criminal activity, but said the murky circumstances of the case warrant more investigation.

Cypriot parliamentarians continue to question the president’s links to the Saudi businessman, and an ad-hoc government commission in late 2020 determined that citizenship applications for members of the bin Mahfouz family contained “false declarations” about plans to move to Cyprus. The commission’s report, which was published in late 2020, found that they hadn't yet moved in.

Bin Mahfouz and five other Saudis applied for Cypriot passports together in 2014, spending nearly 19.8 million euros on commercial and residential real estate to qualify under the citizenship scheme.

Golden Passports by the Thousands

According to the Auditor General, the real estate deals looked suspicious: bin Mahfouz and his associates paid more than twice the market value for some properties.

One deal literally landed close to home for Anastasiades — a luxury villa and two building lots across the street from his private residence in Cyprus’ second city, Limassol.

There’s no evidence Anastasiades had any involvement in the deal, but he chaired a government council that ruled in favor of bin Mahfouz’s application, and there are several other links between the men.

Anastasiades calls bin Mahfouz a friend, but has said his office “has no responsibility” for his citizenship.

Yet official reports and documents obtained by OCCRP show that his hand-picked Council of Ministers disregarded objections from the Ministry of Interior to give Golden Visa applicants, including bin Mahfouz, what they wanted.

Bin Mahfouz, his siblings and business associates were awarded Cypriot passports in January 2015, but there was a hitch: The Ministry of Interior said only one of his two wives could become a citizen of Cyprus, where polygamy is illegal.

His representatives at the Christos Patsalides law firm instead filed separate applications for his two wives. First it applied on behalf of the businessman’s second wife, Nahed Hussain A. Talib, in May 2015. She received her passport that August — just days after Anastasiades used a bin Mahfouz company jet for the first of two unofficial jaunts to the Seychelles.

An application for the first wife, Omaiah Yassin A. Kaki, was then filed in June 2015, and the passport was granted by the Council of Ministers in April the following year. Both women applied for citizenship as the wives of bin Mahfouz.

The Christos Patsalides law firm did not respond to a request for comment. When asked why the Council of Ministers disregarded the Ministry of Interior’s determination, Kyriacos Koushos, the Cypriot government spokesman until earlier this month, said that the allegation was “unfounded and far from truth.”

Other problems with the family’s golden passport arrangements, including questionable real estate deals, wouldn’t become public until years later.

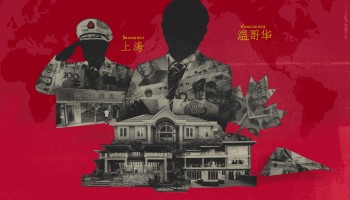

The Golden Friends

Bin Mahfouz is an international businessman whose family has had longstanding ties to the royal House of Saud since his grandfather founded Saudi Arabia’s first bank in the 1950s.

A History of Influence — And Controversy

Bin Mahfouz’s paternal grandfather, Salem bin Mahfouz, was a currency exchanger for pilgrims visiting Mecca until the 1950s, when he was allowed to open the first bank in the country, ending a ban on banking and charging interest.

For many years, the businessman was a shareholder in Al Murjan Group, a family-owned conglomerate founded by Khalid bin Mahfouz in 1994, with real estate, financial services, health care and aviation holdings in Saudi Arabia and the U.K.

He visited Cyprus in search of investment opportunities in June 2014, three months after Anastasiades announced changes in the golden passport scheme aimed at attracting more foreign investment. He met with Anastasiades, Church of Cyprus Archbishop Chrysostomos, and then-Bank of Cyprus CEO John Hourican, among others.

Three months later, bin Mahfouz, his brother, Sultan, and their sister, Eman, filed a joint Cypriot citizenship-by-investment application. They banded together into what was known as a “collective investment scheme,” which meant they could each invest less than the normal minimum of $5 million, as long as their joint investment was at least $12.5 million and they met certain other requirements.

Their group application also included Abdulelah Abdu Mukred Ali and Hani Othman S. Baothman, two men associated with the bin Mahfouzs’ U.K.-based financial services company, Sidra Capital, and a final applicant, Abdulhakeem Hamed A. Waznah, about whom there is little public information. All six are residents of Jeddah, an affluent city on the Red Sea, according to leaked documents.

Another 36 relatives of the investment group executives were also granted Cypriot citizenship through the same or associated applications. The group’s investment in Cyprus included a villa, four apartments, offices, undeveloped land, and three retail properties.

Golden Neighbors and Questionable Investments

Cyprus’s Audit Office reviewed bin Mahfouz’s citizenship-by-investment documents in late 2019, after Cypriot media and political leaders raised concerns about his relationship with Anastasiades. In a report issued in January 2020, it noted several irregularities, including serious questions about overpayment for real estate.

In total, the Saudi investors paid more than 10 million euros over the estimated value of the properties at that time. This should have prompted an alert to MOKAS, the island’s anti-money-laundering unit, the auditors said.

A Problem Portfolio

But MOKAS head Eva Papakyriacou told a closed parliamentary session in February 2020 that she had only recently learned of the controversy through press reports, according to a transcript obtained by OCCRP. It’s unknown if MOKAS or the island’s attorney general, who oversees the agency, ever investigated the matter. Costas Clerides, the attorney general at the time, did not respond when contacted by OCCRP.

Auditors also said the golden passport application should have been rejected because it failed to show that each applicant individually owned a residence in Cyprus, as required by the program.

They noted irregularities in the purchase of the villa and adjacent lots across the street from President Anastasiades’ private home in Yermasοgeia, a high-end Limassol suburb.

The auditors said it was suspicious that the investors paid 4 million euros more than the market value of the villa and lots. The investors would have known the 7.5-million-euro price was inflated, because a financial statement showing the actual property value was included with the purchase agreement, they said.

The overpayment could indicate possible illegal commissions or “other unhealthy practices,” the audit office said in its report.

The Saudis also bought the property in a complicated way instead of just purchasing it outright, which the auditors pointed to as another potential issue.

At the time of the purchase, the villa was owned by a Cypriot developer. The developer also owned a company called Merryvale Ltd., which had no operations or assets other than two plots of land adjacent to the villa.

Bin Mahfouz and his fellow investors purchased Merryvale Ltd. in October 2014, and simultaneously had Merryvale acquire the Limassol property.

They paid 5.5 million euros for the company, and another 2 million to its shareholders — the developer and his wife — as a settlement for a past shareholder loan to the company.

And they made the purchase through yet another company, Pelamore Ltd., which they owned as a group.

Lack of transparency in Cypriot land records makes it difficult to track the ownership of the luxury villa in Limassol, but it has long been associated with the golden passport program.

Limited public records show it was built in 1999, and that in 2002 the adjacent lots were acquired by Russian billionaire Ralif Safin. A longtime Safin proxy in Cyprus told OCCRP that Safin also acquired the villa in 2002.

Safin, a co-founder of Russian multinational Lukoil and a former Russian Federation Council member, was among the first foreigners to be awarded a Cypriot golden passport, in 2008. He is now the sole shareholder of Prato Verde Limited, a registered agent that helped wealthy foreigners obtain Cypriot citizenship. He did not respond to requests for comment.

The property was sold in February 2014 to the developer who sold it to bin Mahfouz through Merryvale.

The legal work for the villa in the final years before Safin sold it off was done by the Soteris Pittas & Co law firm, which had extensive ties to Anastasiades’ former law firm, Nicos Chr. Anastasiades & Partners.

Soteris Pittas told OCCRP that his firm did not know the Saudi investors and never offered any services to them.

Another Controversial Deal

A Golden Discount

The Audit Office started looking into bin Mahfouz’s golden passport application after media reports about Anastasiades’ use of a bin Mahfouz private jet for an official trip.

The president’s office told the auditors that bin Mahfouz offered the jet at a discount, while the estate of the late Chris Lazari, a Cypriot expat who made his fortune in U.K. real estate, covered the balance of the bill. This arrangement saved taxpayers almost 3.5 million euros for multiple trips from 2016 through September 2019, the president’s office has said.

Anastasiades has attributed the discount, nearly 600,000 euros over three years, to his friendship with bin Mahfouz.

The Audit Office found no wrongdoing in the gifts, but recommended limits on the size of such donations and consideration of the donors’ citizenship or residency, as well as any public contracts the donor might have, to avoid the appearance of bribery.

Bin Mahfouz has had some interest in Cypriot public works. A company owned by his family was involved in a proposed VIP terminal construction project with Hermes Airports Ltd., which operates state-owned commercial airports at Larnaca and Paphos. The Saudis’ company has since backed out of the project.

Hermes Airports declined to comment, and a government spokesman did not respond to questions about the terminal project.

In addition to discounts related to official trips, bin Mahfouz has afforded Anastasiades use of the plane for personal trips, including at least one expensive flight for free.

In August 2018, the president and his extended family flew to the Seychelles on a bin Mahfouz jet, as guests of the businessman. This free ride has been questioned by the Audit Office.

In a letter dated January 20, 2020, Anastasiades told auditors the Larnaca-based luxury jetliner was previously scheduled to fly to the Seychelles, where the bin Mahfouz family was on holiday, and that his “friendly relation” proposed taking the president’s family, too. The group included the president’s wife and adult daughters, who are partners in his old law firm.

Koushos referred OCCRP to a written statement from the president, who said in 2020 that the free flight did not violate the ethical standards he set for his cabinet, but “the use of the aircraft for the trip in question could have been avoided.”

That code of conduct forbids taking personal invitations or hospitality from foreign governments, legal entities and individuals whose activity is related to the official’s portfolio. Any gifts valued at more than 150 euros must be declared.

A charter jet flight from Cyprus to the Seychelles would normally cost up to 800 times that amount.

The president’s use of bin Mahfouz’s aircraft remains an ongoing topic of debate in Cyprus’s Parliament, which questioned a civil aviation official during a February 4 Audit Committee special session.

The official told lawmakers that a Boeing 767 operated by the bin Mahfouz family’s Jet Stream Aviation company flew from Cyprus to the Seychelles on August 3, 2015, and returned 10 days later. The flight was designated “Code 1” to indicate that a head of state was aboard, but no EU-required manifest naming the 14 passengers was filed, the official said.

The trip stands out because it was not announced by Cyprus’s Press and Information Office, though other presidential trips in the same time period were. Anastasiades did meet Seychelles President James Michel on August 7, but the rest of his visit remains shrouded in mystery.

Earlier, Anastasiades told another committee that he paid for the flight in 2015 out of his own pocket, but offered no other details.

Parliamentarians have since sent the president a long list of questions, including demands to know who paid for the flight, who was on it and even how much baggage was transported.

In January, President Anastasiades said in an interview with Cypriot newspaper Politis that his Saudi friend had not received any favors from him, and that after the scandal broke, bin Mahfouz had even sought to return his citizenship. It is unclear whether he has done so.