Resident Valodia Tskhovrebashvili says that he cannot do anything in his yard during the day. “The smell is so bad I can’t breathe,” he says. “I try to escape the odor by staying inside, but it comes into the house through every hole.

“In addition, we have problems with insects and black crows. That started after the opening of the landfill.”

Residents say that when they have tried to get government officials to resolve these complaints, they get only a runaround from agencies that say they are not responsible.

To sort out what happened in Didi Lilo, it is necessary to go back to 1994, when a group of 17 residents formed a cooperative to rent a 13-hectare plot of land.

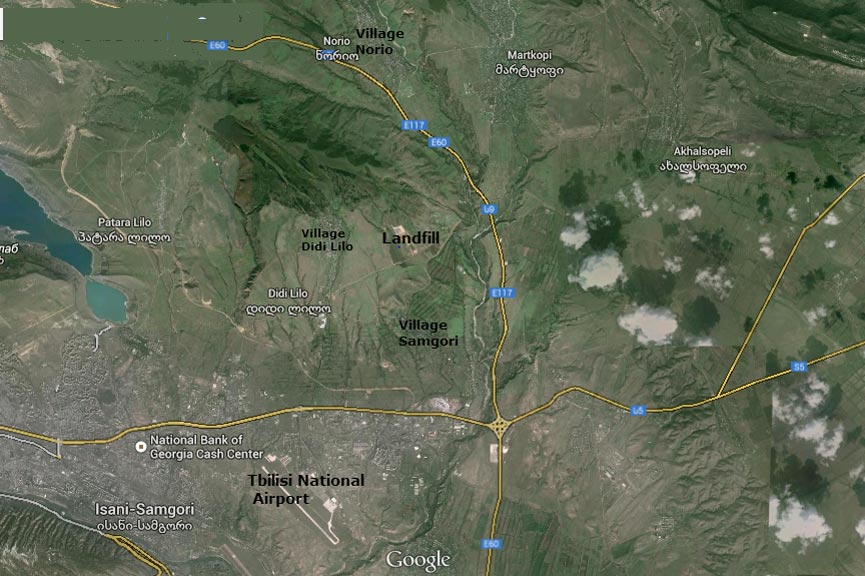

Didi Lilo is a village of 500 families located on dry flatlands at the foot of a range of hills about 20 kilometers from Tbilisi and about 7 kilometers from Tbilisi airport, as the crow flies. And the crows do fly—swarming the landfill and creating a flight risk for planes.

“We used this land for agricultural purposes,” said cooperative member Luka Sakhltkhutsishvili. “It was high quality land.”

In 2006, the members of the cooperative decided to buy the 13 hectares outright. They continued to farm the land until 2010, when two events occurred: the Public Registry began creating a digital map of the territory, and residents of the nearby village of Norio began loudly objecting to a plan by the City of Tbilisi to locate a landfill near their homes.

The village of Norio, which is about two kilometers further from the airport, is located on the site of the historic 1625 Battle of Martkopi between the Georgian and Persian armies. A coalition of Norio inhabitants and historical preservationists successfully argued that the proposed landfill shouldn’t be established so close to the battle site.

So the Tbilisi city government quickly relocated the dumpsite close to Didi Lilo. Says villager Giorgi Gabatashvili, “As soon as the machines and workers appeared here, we immediately started protest actions, but they broke up our rallies and demonstrators who had government jobs were fired.” A field across the road from the landfill is filled with plastic bags.

A field across the road from the landfill is filled with plastic bags.

“We sent official letters to Parliament and City Hall, but we did not get any answer from them. We have a right to live in a healthy environment according to our constitution, but our government took that right away.”

The new Didi Lilo landfill site covers 37 hectares. According to Georgia land documents, there were 60 different small pieces of property registered on that site before June 28, 2010.

Among those was the 13-hectare site owned by the Didi Lilo cooperative. Before June 28, 2010, the entire 13 hectares appeared in the registry under cadastre code number 810800669. Typically, cadastre codes, once assigned, are permanent and should stay with a property forever.

But in the online Public Registry database, the land with cadastre code 810800669 no longer exists. Instead, the cadastre code for the entire landfill territory is 810933349. An official explanation on who changed the cadastre codes and why remains unavailable.

The cooperative members wrote several letters to the Public Registry, and finally received a reply on February 18, 2014. The Public Registry wrote that the former owners could no longer register the property because some of that land was located on other people’s property.

In 2012, the United National Movement government of former President Mikheil Saakashvili was voted out of office and replaced by the Georgian Dream coalition headed by Bidzina Ivanishvili. After the change, cooperative members filed their first complaint with the Prosecutor’s Office on March 15, 2013. After a second letter was sent, the Prosecutor’s Office said they would begin an investigation. According to spokesperson Eka Chichua, the nearly year-old investigation continues, and if there are any new details, the former landowners will be informed.

One of the former landowners, Marina Tsofurashvili, met in the summer of 2013 with Ekaterine Kereselidze, the head of the Public Registry. Kereselidze sent her to the Tbilisi city government’s Property Management Agency in order to reach an agreement.

“They offered us, instead of our plot, a smaller 5-hectare piece of land across the road from the landfill,” Tsofurashvili said. “But we were against this deal. Cultivating the land near the landfill is impossible. There is a terrible odor, and big birds which can damage the whole harvest.”

In January of 2013, the residents protested by blocking the access road to the landfill for several days, to no avail.

No government body will take responsibility for the change in land registration, and OCCRP’s attempt to find out what happened led to a carousel of finger-pointing:

Vano Tsartsidze, head of Registration and Cadastre department at the Public Registry, said the 13 hectares in question was on land located within Gardabani district. (Gardabani is a municipality with a population of 107,000 located 35 km from Tbilisi, farther from the airport).

Gardabani government officials said it was the responsibility of Tbilisi city government.

Tbilisi city government said it was the responsibility of the Ministry of Economics.

The Ministry of Economics said it was the responsibility of the National Agency of State Property.

The National Agency of State Property said it was the responsibility of the Public Registry.

For the second time, the Public Registry said it was the responsibility of Gardabani city government.

Tornike Shiolashvili is the head of Tbilservis Group Ltd, a company set up to manage the landfill by Tbilisi city government, which holds 100 percent of the company shares.

Shiolashvili says the odor complaints are exaggerated. “The residents said three years ago there was a terrible smell. This is impossible because there was no trash scattered three years ago. By 2012, there may have been enough accumulated trash for the chemical process that produces the smell to have begun. Maybe the odor is more noticeable now,” says Shiolashvili.

Liquid runoff created as the garbage is dumped and crushed makes the smell worse. For the past three years, the runoff has been collected in a small pond lined with a synthetic membrane, and it is occasionally poured onto the garbage heap to help prevent serious fires. But because the runoff is unfiltered, it greatly adds to the odor problem.

The first garbage pile, on a 7.9-hectare parcel, will soon be full. Tbilservis Group Ltd said it has budgeted US$5.476 million to build a second trash pile on 10 more hectares. Shiolashvili says the new budget includes money for a filtering system that will reduce the runoff odor.

According to Shiolashvili, the Tbilisi city government allocated about $US6.896 million in its 2010 budget to construct the landfill. Above ground, about all you can see is an administration building and machinery to weigh and disinfect vehicles.

Shiolashvili says every expense is clearly listed in the landfill budget. But despite three official requests, Tbilisi city government has so far only produced documents listing expenses of US$160,167 for a preconstruction report, a technology plan, and for geological and archeological surveys.

Georgian Young Lawyers Association attorney Sulkhan Saladze also wrote official letters seeking this budget information. The reply he received states that the documents are stored at the Ministry of Economics. The Ministry of Economics says they have no documents regarding the landfill’s budget.

After the village protest in January of 2013, the Ministry of Environmental Protection of Georgia spent two weeks conducting an inspection. Tamar Sharashidze, the Ministry’s acting head of Ecological Expertise and Inspection Department, listed the following problems:

There was no filtration system to deodorize garbage liquid runoff.

There was no system to pump liquid runoff to the top of the pile to help prevent fires.

The first garbage pile was located on 7.9 hectares, not 14.9 hectares as was listed on the landfill plan.

There were no radiation detectors.

According to Sharashidze, these violations are the reason the landfill stinks. The Ministry sent this list of violations to Tbilisi City Court, which fined Tbilservis Group Ltd about US$2,875 on April 25, 2013 and gave them 180 working days to fix the problems, which landfill company manager Shiolashvili called “not dangerous or alarming”.

The Ministry of Environmental Protection conducted another investigation in November of 2013. According to Veriko Aghlemashvili, head of the Environmental Pollution Control Department, Tbilservis Group Ltd complied with only one recommendation – they purchased one additional mechanical device to scare the birds. Crows are constant visitors to the landfill

Crows are constant visitors to the landfill

On several visits, the landfill staff did not allow a reporter to enter, but even from outside the fence, one can see the huge number of crows flying over or picking at the garbage.

Lilo Landfill is located about 7 km from Tbilisi International Airport. According to International Civil Aviation Organization standards, no open landfill should be located within 9.6 km of an airport, precisely to lessen the odds of a flock of birds flying into a plane’s engines and causing a crash.

Nikoloz Mzhavanadze, head of Georgia’s Union of Human Rights Defenders, received an official letter from airport operating company TAV Georgia stating that there were three incidents of birds striking aircraft in 2011 and seven incidents in 2012.

Gvanca Kereselidze, a public relations representative for the Georgian Civil Aviation Agency, says birds aren’t the only problem. “An open landfill means fire and smoke, which can cause a pilot to lose sight of the runway,” Kereselidze said.

According to the Ministry of Environment Protection, Tbilservis Group Ltd was required to use bird scaring devices because the landfill is so close to the airport. These devices produce sounds that mimic predators hunting the birds, and also mimic bird distress cries.

Tbilservis Group’s Shiolashvili thinks buying the devices is a waste of money. “It’s impossible that birds from the landfill appear at the airport. We will buy these scaring devices, which are requested by the Ministry. But it will be just an additional vanity expense.”