Lenin Street in the little Russian town of Goryachy Klyuch is an inexplicably raucous place, judging by local court records that show dozens of arrests there over the past two years for cursing and creating a public nuisance.

Or, as at least one jailed suspect has spelled out in detail, the odd arrests may be evidence that the Federal Security Services (FSB) in the Krasnodar region of southern Russia uses police stations and pliant local courts to hold its suspects in what amount to secret prisons where they can be repeatedly grilled and tortured. Charges against these suspects are trivial, like using foul language in a public place, but they’re good enough to hold anyone for up to 15 days. And they can be repeated again and again by filing new, equally trivial charges...

Yegor Skovoroda, a reporter for Russian media outlet MediaZona, examined police and court records and found numerous people detained in this way. These cases didn’t just young Muslim men from Central Asia suspected of terrorist ties, but also local businessmen and a couple of workers who had gotten their hands on an illegal firearm.

One of the victims was Parviz Muradov.

When It Rains, It Pours

At 4 a.m. on Aug. 8, 2017, The Moscow-Kyiv train stands at the platform in Suzemka Station, near the Ukrainian border. Rain drenches the streets, and Russian border guards shake spray from their umbrellas as they enter the car.

They check the passengers’ documents meticulously, finally reaching a dark-skinned man and a pregnant woman in a peach-colored dress. The guard mutters something and leaves with the man’s passport. “Everything will be fine,” whispers the woman. The rain pours and pours.

“Get off the train,” says the border guard when he returns. “You’re not allowed to leave Russia.”

A man in a suit and tie sitting opposite interrupts, demanding to know what’s going on. He is Magomedshamil Shabanov, who’s accompanying then-32-year-old Parviz Muradov and his wife Svetlana at the request of Civic Assistance, a human rights NGO. This is Muradov’s second attempt to leave Russia. The first time, a couple weeks prior, he endured a long interrogation by an FSB officer.

Shabanov calls the officer in charge of the border guards’ shift and demands some document forbidding his client to leave Russia. The officer protests, showing notes against Muradov’s passport on an electronic database.

He finally relents: “It’s just that… Whatever. Safe journey.”

The train judders and starts. After half an hour it reaches the Ukrainian side, where Muradov and Svetlana request political asylum. They had decided to flee Russia after Muradov was tortured by FSB operatives in Krasnodar and then spent more a month in a police station prison cell on fabricated charges.

Nearly a year later, the Muradovs have a new baby daughter. But as of this summer, they are still awaiting the decision of Ukraine’s migration service.

Muradov’s experience offers a glimpse into the how the FSB operates in southern Russia.

Credit: Maria Tolstova

Credit: Maria Tolstova

A New Life, a Fight, and then Trouble

Muradov and his wife Svetlana met in Moscow, where he’d come from Tajikistan in search of work.

A street brawl landed him in prison instead. As he tells it, two drunk men approached him and Svetlana, and one drew a knife. Muradov slammed one of the attackers over the head with a crowbar from his nearby van. In June 2011, Moscow’s Lyublinsky district court sentenced him to five years’ imprisonment.

Muradov says that after his release from a Smolensk area prison, he couldn’t find work in Moscow, so the couple moved to Krasnodar, a region in southwestern Russia that lies between Crimea and the largely Muslim republics of the Greater Caucasus. As other reporting from MediaZona has shown, this region is at the heart of Russia’s often heavy-handed counterterrorism efforts.

At first Muradov worked as a taxi driver, and then, with the money raised from the sale of Svetlana’s Moscow apartment, the couple opened a small shop selling fruit and vegetables.

On June 7, 2017, Muradov was buying a hosepipe when his wife phoned to remind him of a hospital appointment. When walking to the car park outside the shop, he noticed a minivan with tinted windows. Four or five masked men jumped out, shouting “Get down!” They handcuffed Muradov, shoved a bag onto his head, and pushed him into the vehicle, and drove off.

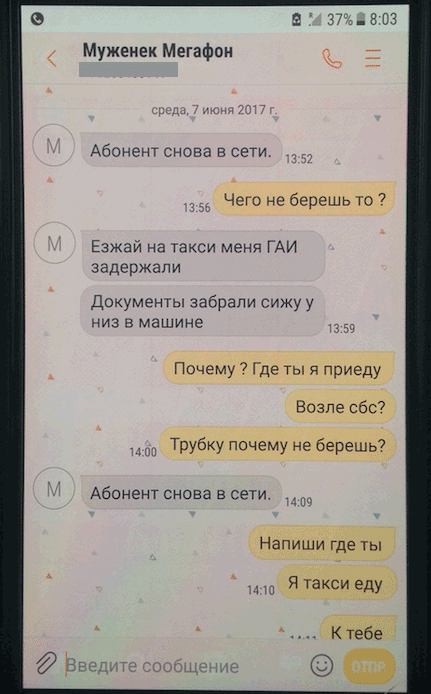

SMS messages received by Svetlana Muradova, ostensibly from her husband Parviz. He asks her to come and meet him, claiming that he has been detained by the traffic police. Credit: Image courtesy of the Muradov family.

SMS messages received by Svetlana Muradova, ostensibly from her husband Parviz. He asks her to come and meet him, claiming that he has been detained by the traffic police. Credit: Image courtesy of the Muradov family.

The experienced taxi driver could tell that he was being taken somewhere near the Krasnodar train station. He was brought to the fourth floor of a building.

When Muradov didn’t show up at home, Svetlana phoned several times, but he didn’t answer. Then, at 13:56, the telephone buzzed with an SMS: “Come in a taxi. The traffic police have detained me. They’ve taken my documents, I’m sitting with them in their car.”

Svetlana didn’t buy it. “I suspected it wasn’t really him. He wrote, ‘Come in a taxi’, and never once in his life has he said, ‘Come here,’” she explains. Svetlana tried to phone him again, and heard a message that the subscriber was not available. “He’d disappeared.”

Meanwhile, Muradov says, he was being tortured. “First they beat me, then tortured me with [electric] shocks,” he recalls. “They said ‘We’ll shove a stick up your ass, and then you’ll tell us everything.’ But how? What could I do? Then they started to ask me about people I didn’t know and had never seen before in my life. I said that I didn’t know anything and wasn’t trying to deceive them. And they tortured me and tortured me again. ‘Who have you been talking with? Did you spend time in prison? Right, so maybe you spoke with people there?’”

Muradov says that while he’d been in prison he’d gotten to know a fellow Tajik, Fazlidin Bazarboyev, who was released a few months before him and was deported back to Tajikistan. Sometimes he sent messages to Muradov.

“He wrote that he was planning to leave and start work in Turkey. Well, I said, it’s good that there’s work there. And after a couple of months he wrote that he was planning to travel to Syria for work,” says Muradov. Muradov found that strange. “What work could there possibly be in Syria? I don’t know,” he said. He stopped answering.

The interrogators showed him photographs of people he didn’t know. The only one he recognized was Bazarboyev. “I said that I knew that guy, that I had been in prison with him. [They] then said that they wanted me to get back in contact with Bazarboyev to find out ‘how they enlist people.’”

Muradov protested that he hadn’t been in touch with Bazarboyev for six months.

When his captors told him they were neither police nor detectives but FSB agents, Muradov stopped arguing and agreed to cooperate with them. He recalls that the FSB operatives instructed him to go to Goryachi Klyuch, a town he’d never been to, and visit the local mosque to look for extremists.

Credit: Maria Tolstova

Credit: Maria Tolstova

Mind your language

Goryachi Klyuch lies in the foothills 50 kilometers south of Krasnodar, the regional capital. It’s a small resort town (the name translates as “Hot Spring”) known for its sanatoria and parks. But FSB operatives don’t come here to relax.

As Svetlana was filing a missing person’s report on him, FSB agents were delivering Muradov to the police station in Goryachi Klyuch. There, he was accused of “petty hooliganism.”

According to the town police, Muradov was detained for swearing loudly near the eternal flame, a war memorial on Lenin Street, a pine-lined boulevard in the town center.

Muradov didn’t deny his “guilt” in court; his captors warned him that if he resisted, he would be held even longer. He was sentenced to three days behind bars.

When Svetlana arrived after that time, she found her husband covered with bruises, his face cut and bloody, and his wrists rubbed sore from the handcuffs.

And he wasn’t getting out. “They say I’ll stay here for longer,” Muradov told her. “They have an order to keep me locked up.”

On June 11, four days after his initial arrest, the court found Muradov guilty of another offense – using foul language on Lenin Street. Judging by their report, he was detained near the police station just fifteen minutes after his release.

This story repeated itself five times in all. As soon as his sentence drew to an end, Muradov would be found guilty of the same charge again. Only the address on Lenin Street differs in the various police and court reports.

Muradov said that FSB operatives, one of whom he recognized from Krasnodar, visited him several times, telling him: “If you mislead us or try to run away, we’ll lock you up for 15 years and then deport you back to Tajikistan to serve a jail sentence there. Do you know what things are like [inside Tajik jails]?”

While traces of his torture lasted for more than a week, doctors never documented them, says Muradov. On his first night in Goryachi Klyuch, police took him to a medical examination. He already had a bruised back and a swollen hand, but “the doctor said, ‘You’re fine’, and wrote a certificate to prove it.”

Svetlana soon found the lawyer Shabanov, who met Muradov in his cell and filed complaints. Muradov was finally released for good on July 10 – after 34 days in jail.

He hasn’t returned to Krasnodar since; Svetlana did so only long enough to sell the family’s property.

Muradov told of meeting a Russian man at the detention center who had also been beaten for having spoken to friends in Syria. He said that the police officers didn’t hide that he was being detained on the FSB’s instructions, or that similar detainees were regularly brought to Goryachi Klyuch.

According to Muradov, police officers told him they had just brought in “another two” on June 26; the date of one of his court hearings. The website of the Goryachi Klyuch city court indeed shows that two young Chechens, Yuni Murdiev and Adam Sugaipov, had been arrested on June 25 — for using foul language on the town’s streets.

Credit: Maria Tolstova

Credit: Maria Tolstova

Disturbingly Similar Stories

Unlike Muradov, Murdiev and Sugaipov were eventually convicted, in March 2018, of attempting to travel to join a Syrian terrorist organization. According to case materials, the pair had turned themselves in and confessed at the Krasnodar region FSB directorate – the same building where Muradov says he was tortured.

According to the FSB, Murdiev and Sugaipov were released June 24 and immediately headed for Goryachi Klyuch, where they were detained for swearing in a public place. They were arrested again on the same charge the following day. They appear to have been “the other two” police officers mentioned to Muradov.

Just like Muradov, Sugaipov and Murdiev were then arrested repeatedly for cursing until July 12, when both were officially detained and questioned as terrorism suspects. Lawyer Islam Khuchiyev says their confessions are the only proof of Sugaipov and Murdiev’s guilt and wonders why the FSB did not simply detain them immediately after their first questioning, instead of sending them to Goryachi Klyuch.

Decisions by the Goryachi Klyuch city court yield the names of about a dozen people, Russians and Central Asians, who in 2016 and 2017 spent weeks under arrest, accused of petty hooliganism. All allegedly swore out loud, usually on Lenin Street.

All served a period of administrative arrest in the local police station, after which they were either deported, detained by FSB investigators, or in a few cases made to do construction work for the police, then released.

Judging by court orders, Tajikistani citizens Alisher Faizoyev, Alichon Dzhurayev, and Akmal Yusufkhonov came to Goryachi Klyuch expressly to swear on its streets, for which they were promptly jailed. Each was arrested three times and spent 28 days in the city police station. The FSB then released them, only to place them into pre-trial detention, charged with attempting to join the Islamic State.

It’s not just suspected terrorists who were treated this way.

“The FSB simply locked us away there,” says Pavel Stukalovsky, who was also arrested in Goryachi Klyuch for obscene language. He says that FSB operatives detained him in February 2016 for possession of a firearm which he and his neighbor Anton Krivomazov were trying to sell. The buyer turned out to be an FSB operative.

“We were sent to Goryachi Klyuch so that nobody had any contact with us,” Stukalovsky explains. “We were taken from the prison cell straight to the police station, from the police station to the courtroom, then back – that’s how we spent a whole month there, with no end in sight.” Records show it was a 30-day detention.

It’s not clear how many times the two men were separated during their detention or why. Stukalovsky says he was beaten, and Krivomazov told him that the beatings continued in the Krasnodar FSB headquarters. “As soon as we were brought in, of course, they beat us… And even though my head was badly injured, the doctor kept saying there was no problem,” says Stukalovsky.

While detained, recalls Stukalovsky, FSB operatives pressured him to sign various confessions. After their period of arrest ended, Stukalovsky and Krivomazov were finally officially questioned by an investigator, who charged them with an attempt to smuggle and illegally market weapons before releasing them on bail.

“They understood that we weren’t terrorists; we were nobody. They really believed we had some mountain of guns, but there was just one from the ‘70s, which was already rusty,” laughs Stukalovsky. On June 15, 2016, a court in Krasnodar sentenced him to one year and eight months’ imprisonment. Krivomazov got two and a half years.

Credit: Maria Tolstova

Credit: Maria Tolstova

Catch a Criminal, Concoct a Crime

“This has become a very frequent practice in recent years,” says human rights lawyer Vladimir Gaydash, recounting other cases where FSB detainees are arrested under falsified administrative charges. While the suspects sit behind bars, says Gaydash, operatives investigate “to what extent he is really guilty” and discuss what’s to be done with him.

He says that the courts understand perfectly well that the practice is illegal, and that if a lawyer turns up to help the detainee, then “the situation ends immediately.”

One of Gaydash’s clients, Rustam Dzhetiyev, was detained at the police station in the village of Novodzhereliyevskaya near Krasnodar on Feb. 16, 2014. Dzhetiyev’s wife says that, late one night, 10 armed men in masks burst into their home in the village and began conducting a search. They forced her husband into handcuffs, shoved a bag over his head, and took him away.

When his wife tried to file a complaint the next day, she discovered that the district court in the nearby town of Bryukhovetskaya, which serves the wider municipality, had arrested Dzhetiyev for 15 days for disobeying a lawful order from a police officer. Dzhetiyev was not released after 15 days, however; his detention was extended when on March 3 the court arrested him on the same charge and meted out another 10 days.

But it didn’t end there. After the end of this period of detention, Dzhetiyev was driven to the village of Kalininskaya, the center of the neighboring municipality. According to a local court he “provoked a scandal with no good cause” and used foul language outside a village shop. He was arrested again, this time for 15 days.

Documents relating to Dzhetiyev’s case indicate that he caused this scandal some 45 minutes after being released from detention in Bryukhovetskaya, some 60 kilometers away from Kalininskaya. Lawyer Gaydash supposes that Chechnya-born Dzhetiyev was really detained because he has relatives who had fled Chechnya.

In December 2017, Mikhail Matayev, a 26-year old from Dagestan, went missing in Krasnodar. His girlfriend told his father that on the evening of Dec. 1, seven unidentified people seized them outside Matayev’s house and put a bag over his head. Both were taken to the FSB directorate in Krasnodar.

Though she was released after questioning, his relatives only discovered his whereabouts Dec. 9. It turned out that the Belorechensky district court had sentenced him to 15 days’ imprisonment for petty hooliganism.

When Gaydash visited Matayev at a temporary detention center in Belorechensk, a town 80 kilometers from Krasnodar, the young man described being beaten and tortured with electric shocks.

After seizing him, Matayev’s captors initially demanded that he confess to giving bullet cartridges to an unknown person. According to Matayev, “round metal objects, like a bullet cartridge to the touch” were placed in his hands, and the tortures and beatings continued for most of the night. They took him to the Belorechensk police station on the following day.

Matayev was charged with illegal possession of ammunition, but the case was dropped immediately after he was released from detention. At the same time, Matayev’s father withdrew statements he had sent to human rights organizations.

A happy end to an unpleasant story? Mikhail and his relatives think so, says human rights activist Oleg Orlov. “But [what of] the abduction, tortures, and administrative case conjured out of nowhere, which later became a criminal case? Apparently, from their point of view, these are regrettable but isolated cases.”

Credit: Maria Tolstova

Credit: Maria Tolstova

Cutting corners

The term “secret prisons” usually refers to unofficial detention centers where people picked up by the security services are kept without any legal basis or official registration. As a rule, the practice is associated with torture.

Novaya Gazeta has written about “secret prisons” in Chechnya, where the security services have detained and tortured gay men. Republic has reported that FSB operatives kept people suspected of terrorism in a “secret prison” in the Moscow region (which probably refers to not one, but several locations). Those who spent time there claim they were tortured; they were only officially detained once the operatives had received the testimonies they wanted.

Administrative arrests, such as those the FSB in Krasnodar use, differ from “secret prisons” as it’s difficult to say that those who disappear have been “kidnapped.” They are formally arrested by a court, though not on the real charge they’re probably suspected of. While in temporary detention, they are unofficially visited by the security services. Frequently, according to victims, these arrests are preceded by torture.

“In a way it’s actually quite sloppy work, as it leaves obvious traces,” says lawyer Dmitry Dinze, who represents Abror Azimov, a suspect in the 2017 St. Petersburg metro bombing. He notes that it’s difficult to prove that Azimov was kidnapped or unlawfully detained. In cases such as these which involve temporary detention centers, continues Dinze, the formal reasons for detention are all documented.

Kirill Titayev, Senior Researcher at the Institute for the Rule of Law, says that such practices were widespread from the 1990s until the mid-2000s.

“This is a well-known technique transparently devised by law enforcement agencies. They have a clear line as to why this can be done,” Titayev says.

MediaZona sent a detailed request to the FSB directorate of the Krasnodar Region concerning all the cases mentioned in this article, but by the time of publication had received no response.