After Belarus’ state potash producer was slapped with sanctions in 2022, strongman Alexander Lukashenko warned that the trade would have to go “quiet” in the future — like “selling arms,” he said.

Potash, a red-tinged mineral rich in potassium, may appear unworthy of such subterfuge. But as a crucial component of fertilizers used on crops around the world, the commodity is in high demand and its availability is considered key to ensuring global food security.

In Belarus, home to one of the world’s biggest potash deposits, the industry is also an economic lifeline for Lukashenko, who has found himself increasingly isolated by the West for his regime’s rights abuses, corruption, and aid to Russia’s war effort in Ukraine.

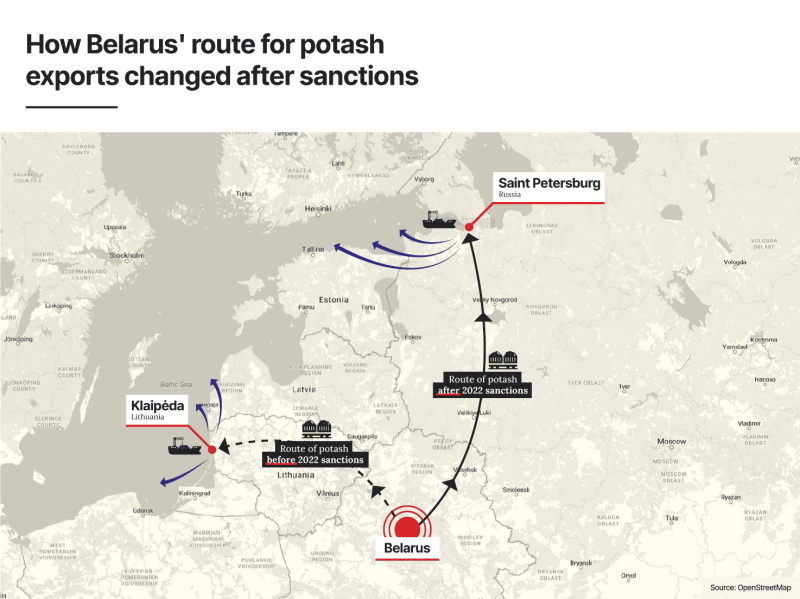

For years, landlocked Belarus shipped its potash around the globe through a port in neighboring Lithuania. When that maritime access was cut off by the 2022 EU sanctions, Belarus began routing its shipments through Russia to countries where sanctions were not in place.

But not all the loose ends have been tied up. An investigation by OCCRP’s Belarusian partner BIC found that Belarus’ potash export chain still involves a violation of EU sanctions, due to the involvement of a Cypriot company with hidden connections to a former high-level official from Lukashenko’s administration.

Contracts obtained by BIC show that Belarus’ state potash monopoly, Belaruskali, has been paying a Cyprus-registered intermediary, Dimicandum Invest Holding Ltd., to move potash exports the short distance from St. Petersburg’s train station onto vessels in the city’s port.

Since Dimicandum is registered in the EU, this violates the sanctions that bar European firms and citizens from providing services or products to sanctioned entities like Belaruskali, according to experts.

Why the company was brought into the logistics chain, given its risk of sanctions violation, is unclear. A deeper look at Dimicandum’s role raises even more questions.

The company appears to constitute an unnecessary financial burden for Belarsukali, according to an internal report leaked to reporters from a state organization that described some of the planned payments to Dimicandum as “unjustified.”

And despite being officially owned and directed by a Cypriot national, power-of-attorney documents show that the power to make deals on behalf of Dimicandum was granted to the former deputy chief of Belarus’ Presidential Property Management Department, Andrey Sviridov, who served under one of Lukashenko’s closest allies, Viktor Sheiman.

The Property Management Department owns dozens of businesses and has a wide remit, including to support the “functioning of the national organs of government.” It reports directly to the president.

Grodno Regional Executive Committee, 2010-2024

Andrey Sviridov, former deputy chief of Belarus' Presidential Property Management Department.

Sviridov confirmed to reporters that he is Chief Financial Officer at Dimicandum, but denied wielding any further influence or signing contracts with Belaruskali.

Belaruskali did not respond to requests for comment, and Dimicandum and its Cypriot director could not be reached. But Damelen Consulting Ltd, the Cypriot firm that serves as Dimicandum’s secretary, denied the firm had done business with Belaruskali.

“We weren’t aware that any contracts were signed or that anyone was doing this on behalf of the company,” Damelen’s director, Olena Brovkina, told reporters by phone.

With Lukashenko’s executive branch tightly controlling the state and much of the economy, watchdogs say graft runs rampant in Belarus’ government and state-run enterprises. Since the sanctions came into play, public oversight of state-run enterprises has been further curbed by the government’s decision to stop releasing trade statistics on many exports, including potash.

Lev Lvovskiy, academic director of the Belarusian economic think tank BEROC, said that while he could not make a definitive assessment, the arrangement between Belaruskali and Dimicandum could be an example of a “very common scheme for Belarus” in which intermediaries are used to siphon off funds.

“It is usual for Belarus, when something produced by the government is exported, [that] there is some intermediary firm, which is some small link on the way, and then this firm collects most of the money and it’s just corruption,” he said.

Cyprus is also a common offshore destination for Belarusians looking to obscure their ownership of a business or keep money from the hands of the state, he added.

Reporters could find very little publicly available information about Dimicandum’s commercial activities since its founding over a decade ago.

The company has no obvious commercial presence or website, and despite requirements to file annually, only submitted financial statements to Cyprus’ business registry for the years 2013 and 2014. The statements, which declared revenue of 19.1 million euros and 39 million euros respectively, describe the company’s principal activities as “general trading, provision of consultancy services and holding of investments.”

However, evidence from an investigation by Ukrainian law enforcement suggests the company may have been used as a vehicle for sanctions evasion in at least one previous incident — a luxury car scheme busted by authorities in 2023.

“My Godfather is the Second Man in Belarus”

New Route, New Problems

Belaruskali, the state-run potash monopoly, employs some 17,000 people across its seven mines, where potash is extracted from a 360-million-year-old deposit deep underground. Only a handful of nations are home to such large reserves, with Belarus ranked second worldwide after Canada.

Algimantas Barzdzius/Alamy Stock Photo

Belaruskali cargo transiting through Lithuania.

Hailed by Lukashenko as a national treasure, Belaruskali accounted for nearly a fifth of the world’s market share of potash in 2019, plus some 4 percent of Belarus’ GDP and 7 percent of its exports.

But it too was roiled by the anti-government protests that swept the nation in August 2020 after Lukashenko declared victory in a disputed election.

Belaruskali workers were among those who joined the peaceful protest movement, which saw tens of thousands of citizens flood the streets — only to be met with violent repression by security forces, followed by a sweeping crackdown on civil society.

In 2021, Belaruskali received its first sanctions blow from the U.S. for serving as “a major source of tax revenue and foreign currency for the Lukashenka regime,” which Washington condemned for corruption, rights abuses, and repression.

The following year, the EU banned all potash imports from Belarus in response to the country’s assistance in Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine. It imposed sanctions on Belaruskali for supporting the regime and punishing the employees who had taken part in the protest movement.

Since then, trains carrying Belaruskali potash have been diverted from Lithuania to Russia, including to the Great Port of St. Petersburg, where shipments are dispatched to buyers like China, Brazil, and Indonesia that have not imposed sanctions on Belarus.

James O’Brien/OCCRP

According to a Russian media report, one of the port’s terminals, Baltic Ship Mechanical Plant, was rebuilt specifically to accommodate Belarus’ new needs, and handled about a third of the country’s potash exports in 2023.

But instead of working directly with the port, which offers its own transshipment services, a contract leaked to BIC shows Belaruskali has been paying Dimicandum to move its potash from the St. Petersburg’s Avtovo railway station onto ships at the Baltic Ship Mechanical Plant terminal.

According to the October 2022 contract and a supplementary agreement, Dimicandum would be paid $68.6 million to handle the transhipment of 3.4 million metric tons of potash fertilizers through the port the following year. Further agreements suggest the Cypriot company fulfilled its obligations, with Belaruskali agreeing in June and August 2023 to provide advance payments to Dimicandum for future shipments.

Belaruskali’s Contracts With Dimicandum For Potash Transhipment

These deals would constitute a clear breach of EU sanctions, said Tom Keatinge, director of the Center for Finance and Security at the Royal United Services Institute (RUSI) think tank.

“All EU entities, all EU people, are subject to EU sanctions. It doesn’t matter if they’re facilitating trade that is happening outside the EU,” he told reporters.

“So in this specific case, if they’re facilitating trade of potash, a sanctions situation, to entities outside the EU, they should still be investigated. It clearly sounds like a breach of sanctions to me.”

Pavel Slunkin, a former diplomat for Belarus who has also worked as a policy analyst, said he suspected that those involved in setting up the logistics chain didn’t expect the Cypriot company to pose any problems due to the island’s history of catering to Russian and Belarusian elites.

Cyprus, which initially blocked the EU’s effort to pass sanctions against Belarus in 2020, has come under increased scrutiny since Cyprus Confidential, a global journalism collaboration published last year, exposed how its corporate service providers have helped shield such clients from the impact of EU sanctions.

“The EU has been efficient in imposing sanctions, but never was efficient in controlling how things work,” said Slunkin. “Cyprus has been the country that helped with this for many years. So I believe that they just think that this is again something that won’t be punished if they are careful enough.”

When reached for comment about Dimicandum’s alleged sanctions violation, Cyprus’s Securities and Exchange Commission (CySEC), said it could not comment on specific investigations but that it “takes its responsibility to protect investors extremely seriously.”

‘Unjustified Payment’

In the world of international shipping, intermediaries known as freight forwarders are typically brought into a supply chain for their ability to secure the best routes and rates for clients, as well as to handle any documentation or customs clearance.

But Dimicandum does not appear to have a track record as a freight forwarder, and instead of securing better prices for Belaruskali, it actually charged more than the going rate. The St. Petersburg Port itself provides transhipment services, and in 2021 it charged the equivalent of around $11 to tranship a ton of mineral fertilizers, according to a price list from that year.

According to the contracts obtained by reporters covering the year 2023, Belaruskali was to pay Dimicandum nearly double that rate at $20 per ton of potash fertilizer.

An internal report from a Belarusian state organization leaked to BIC shows that the following year, in 2024, Belaruskali planned to pay transshipment fees of $16 per ton to Dimicandum, which would in turn pay $11 per ton.

Some of the planned payments to Dimicandum were described as “unjustified” in the report, whose details cannot be disclosed to protect the source.

It’s also unclear who was making decisions on behalf of Dimicandum during this period.

On paper, the company has been owned by a Cypriot citizen named Galina Akritova Alexandrou since it was founded in 2012. Akritova also serves as the company director.

But the 2022 contracts with Belaruskali were signed by Sviridov — the Belarusian official who had served as the deputy chief of the Presidential Property Management Department from 2019 to 2021.

The power-of-attorney authorizations obtained by BIC show that in September 2022, Sviridov was granted the power to carry out any transactions on behalf of Dimicandum and to act as the company’s representative in settings including the negotiation of contracts. Two months later, he was given further authorization to open and manage bank accounts for Dimicandum.

When reached by phone for comment, both Sviridov and the director of Dimicandum’s secretary firm, Damelen, denied any power of attorney had been granted to Sviridov.

“We have never issued a power of attorney for Mr. Sviridov and we do not know what kind of person he is,” Damelen’s director said.

Sviridov, 40, is not a well-known figure in Belarus — prior to being posted to the Presidential Property Management Department in 2019, he chaired an economic committee in the Grodno region. But his former boss at the property department is a household name: Viktor Sheiman, the army general considered Lukashenko’s right-hand man.

Sheiman has been one of Lukashenko’s closest allies since the strongman came to power in 1994, serving in high-level roles including Secretary of the Security Council, Prosecutor General, and Chief of Staff to the president. He was first sanctioned in 2004 by the EU for his alleged involvement in the disappearance of four critics of the regime, and has since been blacklisted by the U.S., Canada, Switzerland, and the U.K.

Press Service of the President of the Republic of Belarus, 2024

Belarusian President Alexander Lukashenko (left) with Viktor Sheiman (right)

Sviridov and Sheiman appear to have continued working together even after Sviridov left his government post in February 2021. A month later, he was appointed head of a company called Vector Capital Group which Belarusian media have speculated is connected to Sheiman.

A letter obtained by BIC sent from Vector Capital to another firm in 2023 refers to the “our leader” as “V.V.Sh,” the initials of Viktor Vladimirovich Sheiman. (This was first revealed in an investigation by BelPol, an online media outlet made up of former members of Belarus’ military, police, and intelligence services.) In addition to Sviridov, at least two other officials that used to work at the Presidential Property Management Department have been employed at Vector Capital, according to a database created by CyberPartisans, a Belarusian hacktivist group.

Reporters found no direct link between Dimicandum and Sheiman, who could not be reached for comment. Asked whether he or Sheiman was profiting from Dimicandum’s involvement in the potash trade, Sviridov denied it and implied that reporters had falsified the documents using “neural networks.”

“Where did you find this information?” he asked. Out of your head? From schizophrenics? There has never been any such information.”

The Cyprus Investigative Reporting Network (CIReN) contributed reporting