The trial of an alleged member of a notorious gang thought to have stolen more than a billion dollars from unsuspecting tourists across Latin America plodded along in virtual obscurity in Paraguay this week, with witness testimony canceled in the latest of a string of delays.

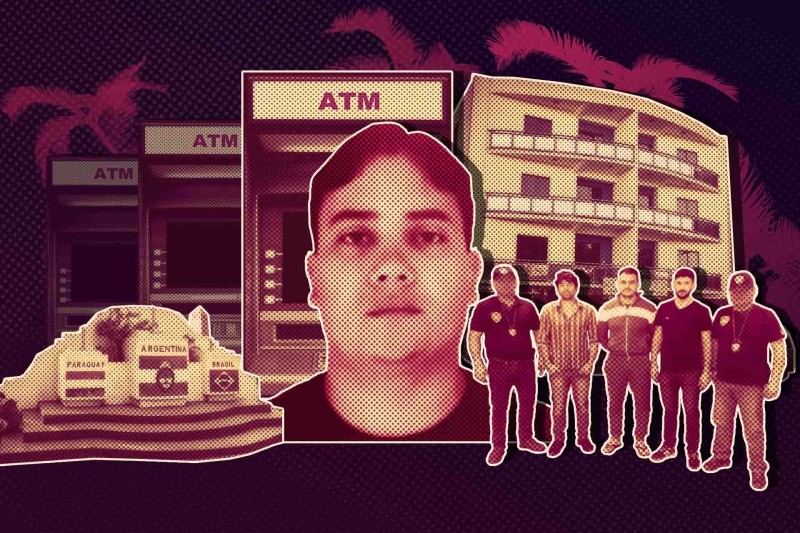

Julio César Belmonte do Amaral faces charges for fraud related to the gang’s main business of stealing victims’ bank card details by tampering with ATMs, then withdrawing their money using cloned cards. The Brazilian was singled out by a fellow gang member as a leader of the group’s expansion into Paraguay, where a police source said the gang had also developed a new scam targeting payment terminals at local businesses.

Belmonte do Amaral is the brother-in-law of the gang’s leader, Florian Tudor, a Romanian gangster nicknamed “The Shark.” In 2020, OCCRP published an investigation into the group’s operations, dubbing them the Riviera Maya gang after the stretch of Mexican coastline where they operated. Tudor was arrested in 2021, but he has so far avoided extradition to Romania while Mexican authorities evaluate his case.

While the Riviera Maya gang has garnered headlines in Mexico, the trial of Tudor’s alleged man in Paraguay has received little media attention, and the courtroom has remained almost empty. At the most recent hearing, on August 22, the judge, prosecution and defense decided to postpone police testimonies because they were busy with different trials.

“I want to make it clear that the police are not reluctant. The witnesses are ready to give their testimony," Judge Marino Méndez told OCCRP’s Paraguayan media partner, ABC Color, days after the brief hearing.

Méndez said the file had been backlogged because it was passed between courts — most recently from the Supreme Court to a Sentencing Court — and staff were overextended.

"It’s in the court's interest that it progresses uninterrupted and ends as quickly as possible," Méndez said.

The latest delay followed five others at the court in Ciudad del Este, a city near the border with Brazil and Argentina. Proceedings have been repeatedly postponed; in one case a former prosecutor submitted last-minute notifications that she had COVID-19.

On July 22, a visibly annoyed Méndez was forced to postpone a hearing, because Belmonte do Amaral’s lawyers didn’t show up. The judge said he had only received notice minutes before the trial was due to start that one of the lawyers, Luis Alberto Jiménez, could not attend because he had COVID-19. The other lawyer, Osvaldo Martínez, did not present any documentation to justify his absence.

Reporters could not reach either Martínez or Jiménez for comment. They are no longer representing Belmonte do Amaral, who has been given a public defender.

Mauro Barreto, president of the bar association for Paraguay’s Alto Paraná department, where the case is being heard, said lawyers failing to appear can be one of a number of strategies, known as chicanas, designed to delay proceedings. These, he said, are used to put off trials for so long that criminals serve their entire sentences under house arrest, rather than in prison.

Belmonte do Amaral could receive a maximum sentence of 10 years for charges including participation in a criminal organization, according to Méndez. He has now been under house arrest for five years.

"Everything indicates that he is seeking the dismissal of the case. They use all the mechanisms and means to achieve it," said Barreto, referring to Belmonte do Amaral and his lawyers.

Belmonte do Amaral has been largely confined to a serviced apartment in a hotel in Ciudad del Este since being arrested in Argentina in 2017.

Cecilia Pérez Rivas, a former Paraguayan justice minister who now serves as a national security adviser to the president, told reporters that the decision to hold him in the lawless border city was “irregular” given the obvious flight risk.

As his seemingly endless legal process drags on, OCCRP and partners have delved into Belmonte do Amaral’s past, piecing together details of the gang’s Paraguayan operations from police records and interviews. Reporters also tracked down multiple properties in Brazil that his family members and other alleged proxies for the gang allegedly bought with the proceeds of their scams.

Belmonte do Amaral did not respond to requests for comment.

‘Money You Can’t Even Imagine’

Ciudad del Este lies on the Triple Frontier, where Argentina, Brazil and Paraguay meet –– the most economically productive place in Paraguay, and one of the largest duty-free zones on earth. It is also infamous for corruption, permeable borders, smuggling, and weak law enforcement.

"It's a place where it's difficult to trace cash,” said Irma Llano Pereira, a Paraguayan cybercrime prosecutor who pursued Belmonte do Amaral.

“Cash is brought back and forth between Paraguay and Brazil, buying high-end vehicles or valuable real estate, through which money laundering can occur."

One former Riviera Maya Gang member said Belmonte do Amaral was sent to Ciudad del Este in 2015, tasked with expanding the gang’s business into Paraguay. The move was close to home for the Brazilian, who grew up across the border in the tourist destination of Foz do Iguaçu with his sister, Jucilene Belmonte do Amaral, whom gang leader Tudor describes as his wife. (He is legally married to a Romanian woman).

As in Mexico, where Tudor’s gang was expanding at the same time, Belmonte do Amaral and his colleagues allegedly set to work skimming from local ATMs. The former gang member said they rapidly started making vast amounts of money and that he personally processed more than $100 million for the gang over the course of three to four years.

“I have seen money in my life that you can’t even imagine,” he told Context.ro, an OCCRP member center in Romania. “I was carrying $700,000, $800,000, $1 million in a few days.”

The former gang member said Belmonte do Amaral funneled some of the money back from Paraguay to Brazil, where it would be invested in real estate.

Besides ATM skimming, police say the gang also pioneered another scam targeting local restaurants and other businesses in Ciudad del Este.

Children and teenage “soldiers” would steal a payment terminal from a business, which would then be fitted with a device that gave access to the details of all cards that made transactions. The gang would then reinstall the altered terminal in another business, sometimes with the help of employees, and use it to clean out the accounts of customers who paid on that machine.

By 2016, however, police had started to get suspicious.

Commissioner Diosnel Alarcón, head of cybercrime investigation for the national police force, said that they were contacted by Paraguay’s main card transactions monitoring service about frequent, small withdrawals using Mexican, European, and U.S. cards being made in Ciudad del Este.

Security staff at Visión Banco also alerted police that someone had tried to install a camera and magnetic stripe reader on one of their ATMs in Ciudad del Este. CCTV footage showed two men emerging from a white Kia Sportage SUV and accessing the ATM, one of whom the police thought they recognized as Belmonte do Amaral.

A few days later, police stopped a vehicle matching that description owned by Belmonte do Amaral, which appeared to have been bought with skimmed funds. Inside, they found a magnetic card reader, as well as payment cards that were presumed to be cloned.

Two Romanians, Laurentiu Catalin Bota and Marian Zarcu, were taken into custody.

As part of a wider sweep, police arrested Brazilian Amantino Vargas Neto in the vicinity of an apartment complex in the Triple Frontier city of Hernandarias. In a room in the hotel where he had been staying — rented in the name of Belmonte do Amaral’s cousin, who had been on the run from Paraguayan authorities since 2016 — police discovered card cloning equipment.

Juliana Giménez Portillo, a prosecutor with Paraguay’s Specialized Cyber Crime Unit, said it was the first time police in the country had ever seized such technology, which included fake cards with chips, micro cameras, and magnetic stripe readers used for card cloning.

However, despite the apparent strength of the evidence, none of those arrested are in prison in Paraguay.

In November 2016, Paraguayan migration authorities said Bota, Zarcu and Vargas Neto were fined and expelled from Paraguay for the “production and use of cloned credit cards” and for being in an “irregular migratory situation,” and sent to Brazil. Belmonte do Amaral was arrested in Argentina the following year, and sent back to Paraguay.

Llano, the prosecutor who worked on an investigation into Belmonte, said most card scams in the country are carried out by foreigners, who are usually fined and expelled in part to avoid the risk of them teaching their methods to other inmates in Paraguayan prisons.

Vargas Neto did not respond to a request for comment. Reached by reporters, Zarcu said he had “no relationship” with Julio Cesar Belmonte do Amaral, had “no idea what he was doing,” and he refused to comment on any of the gang’s wider activities.

Bota told reporters he had only learned of Tudor's existence from news reports. He said that at the time of his Paraguay arrest he had been there on vacation, and he had nothing to do with any skimming.

A Brazilian Property Portfolio

Part of the money the Riviera Maya gang made in Paraguay was invested into Brazilian real estate, according to the former gang member, whose claims are supported by the Romanian criminal file on the gang.

In interviews with OCCRP reporters, the ex-gang member described going to Brazil to deliver cash to Tudor’s wife, Jucilene, so she could build a house in Foz do Iguaçu. Using land registry documents, reporters identified several other properties in the town registered in the name of Jucilene, other members of the Belmonte do Amaral family, and other presumed proxies for Tudor.

Jucilene Belmonte do Amaral has four properties in her name in Foz do Iguaçu, reporters found. One was bought in 2015 for a little over $530,000 and the three others were bought in 2019 for a combined $172,000.

In total, between 2014 and 2019, the records show members of the gang and their proxies bought at least 11 properties for just over $950,000. The former gang member, who delivered funds to them in Brazil, said there was no way the proxies could have afforded the real estate on their own.

One property was bought by Cleusa Belmonte do Amaral, the mother of Jucilene and Julio Cesar Belmonte do Amaral, in March 2014 for a little over $25,000 from a person named Johny Araujo do Amaral.

Others were bought by the wife of one of his brothers, Jucivaldo Belmonte do Amaral, who also appears to have been involved in skimming: In 2016, Jucivaldo spent four days in a Florida jail after a police search turned up a plastic bottle cap containing cocaine residue and 46 fake credit cards in a vehicle that he, Johny Araujo do Amaral, and another associate were using.

When Julio Cesar Belmonte do Amaral’s bag was searched at the airport in Paraguay’s capital Asunción in 2014, security officials found a box with Jucivaldo’s name and address in Foz do Iguaçu, containing white plastic credit cards that can be used for cloning, as well as cell phones, cash, and 18 cards from various banks. He was arrested, fined and expelled from the country.

In August of the same year, Jucivaldo’s wife bought two condominium units in the same development for over $23,000 each. She sold them again in 2019.

Tudor and his wife bought another property themselves in the city for 232,400 Brazilian reals (over $100,000) in July 2014, records show. The former gang member shared pictures of an additional luxurious property he said Tudor built about three years later, though reporters were unable to confirm this through property records.

Tudor, his wife Jucilene, Cleusa Belmonte do Amaral, and Jucivaldo Belmonte do Amaral did not respond to questions about the properties and the gang’s activities.

Yet another of the alleged proxies singled out by the family of a different former gang member also bought a property in 2015 and some land in 2019. His wife was the co-purchaser of another property together in 2017.

It seems unlikely that Paraguayan authorities will recover the allegedly illicit funds used to purchase those assets, given the lack of state control described by Barreto, president of the Alto Paraná bar association.

“These groups … do business or trade in Ciudad del Este because justice does not exist here. It's all about money,” said Barreto.

Eduardo Goulart (OCCRP), Jonny Wrate (OCCRP), Lilia Saul (OCCRP) and Tereza Fretes (ABC Color) contributed reporting.