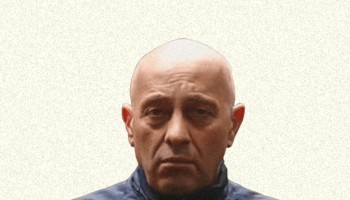

Mileta Miljanić, a Bosnian-born U.S. citizen, is a wanted man in Italy and faces arrest if he so much as changes planes there.

In New York, a 2003 federal indictment of Miljanić remains inexplicably open, with no apparent move to take him to court.

So it’s easy to find the leader of “Group America,” a brutal cocaine trafficking network that operates on at least four continents and is said to be responsible for a dozen murders.

He keeps an apartment in a neat townhouse in the Ridgewood neighborhood of Queens, New York.

His surname is on his doorbell.

Sometimes he even appears on television.

After a fire gutted the St. Sava Cathedral, Manhattan’s landmark Serbian Orthodox church in May 2016, Serbian Foreign Minister Ivica Dačić flew to New York to see the damage. As he spoke to television reporters, viewers in Belgrade spotted a familiar face in the tour entourage: Mileta Miljanić.

Facing criticism, Dačić said he was told Miljanić was a church benefactor “who gave more money than all the other donors put together.”

Records from dozens of countries examined by OCCRP reveal decades of drug seizures and murders linked to Miljanić’s organization. Since the late 1990s, Group America associates have been arrested and charged in Serbia, Montenegro, Germany, Italy, Greece, Poland, South Africa, Argentina and Peru. More than five metric tonnes of Group America cocaine has been seized.

But Miljanić remains safe from arrest, at least in New York and in Serbia, where he made a visit in August, as shown in posts to an Instagram account used by his wife.

In Italy, where investigators have aggressively pursued Group America, authorities say they have been continuously hamstrung by the gang’s connections to the Serbian law enforcement — and perhaps beyond.

“Someone in the United States protects them,” a senior Italian police official told OCCRP in 2015.

A former senior police officer in Belgrade independently offered the same theory.

“I believe the CIA stands behind them. That is why we gave them the name Group America,” he said.

CIA officials declined comment, as have all other U.S. law enforcement or intelligence agencies contacted for this article.

Group America’s astonishing story is grounded in New York City’s Serbian-American immigrant community and in Serbia’s political history, but its operations were largely unknown to authorities in any country until 2001, when a gang insider codenamed Srećko – “Lucky” in Serbian – volunteered to tell the police what he knew.

For hours, stunned officers listened to the story of Yugoslavians who became criminals on the streets of New York, immersed themselves in Serbian politics and graduated to the world of high-volume international drug trafficking.

The police wrote reports, but their attempts to investigate went nowhere.

What is Group America?

The story of Group America begins in 1970, when a young Serb, Boško “The Yugo” Radonjić, emigrated to the United States from what was then Yugoslavia.

Radonjić was both a criminal and a strident opponent of his country’s communist rulers. A supporter of Serbia’s exiled royal family, he did prison time in the United States for a series of bomb plots targeting Yugoslav diplomatic missions.

In the 1980s, Radonjić was an acolyte of Jimmy Coonan, the leader of an ultraviolent Irish-American gang called the Westies that dominated New York’s old Hell’s Kitchen neighborhood. He became head of the infamous gang after Coonan and other leaders went to prison. Under Radonjić, the Westies grew closer to the Gambino Mafia family, led by the infamous “Dapper Don” John Gotti. When Gotti faced racketeering charges in 1986, Radonjić helped tamper with the jury.

Two young Serbs in Radonjić’s entourage would eventually make Group America what it is today.

Mileta Miljanić was born in 1960 in Gacko, a bleak town in the dry grasslands of southeast Bosnia. It’s unclear when he left the Balkans, but he was issued a U.S. Social Security Number in New York City between 1982 and 1984.

He and his best friend, Zoran Jakšić, likely an emigree from Zrenjanin, a small city near Belgrade, worked as Radonjić’s bodyguards in New York. In the 1980s, both were convicted of crimes related to credit card fraud and spent time in federal prisons.

Miljanić served just 20 months of his three-year sentence. Jakšić was also paroled after serving some of his five-year sentence, but ended up back inside for a parole violation. He spent much of the early 1990s behind bars.

The gangsters returned to the Balkans as Yugoslavia disintegrated and Serbian nationalism led by President Slobodan Milošević surged in the early 1990s. Radonjić won support from elements in Serbia’s security service, which provided weapons and shielded them from both local and international investigations.

Around that time, Radonjic’s younger associate, Vojislav “Voya the American” Raičević, joined him in Belgrade and was given control of the gang.

Raičević oversaw the group’s transformation into Group America, a disciplined and secretive international criminal organization focusing on trafficking cocaine from South America to Europe. Authorities also attribute multiple contract killings to members, though they have never won a murder conviction.

The gang maintained its deep ties with the Serbian security service. In a 1997 conversation attributed to a Croatian secret service wiretap, Slobodan Milošević’s son, Marko, and another man were heard discussing Group America leader Raičević, who is described as “working for Boško Bojović,” a senior Montenegrin spy loyal to Milošević.

That was the year Raičević vanished.

In his lengthy confession to the police years later, Srećko said that after the missing Group America leader’s presumed murder, his brother, Veselin Vesko “Little Bear” Raičević, called a meeting to plan a campaign that would root out traitors and exact revenge.

Among the attendees, Srećko said, was Boško Bojović, who was then living in Belgrade as a top associate of Serbia’s intelligence chief.

Srećko said he was told that Raičević’s suspected assassin, Miša Cvjetičanin, was taken to a Belgrade villa and tortured until he named his conspirators. He was then dismembered with a chainsaw.

The subsequent bloody revenge spree against Raičević’s killers saw the murder of two rival gang heads, a police general, two Group America turncoats, and one of their fathers.

After the killing was done, Group America had a new leader: Mileta Miljanić, the man who today lives comfortably in New York.

Then in his late 30s, Miljanić had a reputation as a man capable of both incredible loyalty and calculated cruelty. When police asked Srećko to name gang members they could exploit as weak links, the informant said Miljanić was out of the question.

“Psychologically, he’s really prepared. He knows how to assess people through their feelings, their stories,” Srećko said. “He’s untouchable.”

Miljanić would lead the gang to more complex, and more lucrative, criminality.

Local Terror and Global Reach

Slobodan Milošević was driven from office in October 2000 after mass protests. The reformist government of Prime Minister Zoran Đinđić that followed his ouster cautiously reached out to the West, instituted democratic reforms, and — in contrast to Milošević — was seen as hostile to organized crime.

Group America responded with domestic terrorism.

In 2002, the group was accused of orchestrating the nighttime assassination of police general Boško Buha on the banks of the Danube. In subsequent raids, police recovered a number of weapons, including two pistols and an assault rifle registered to Serbia’s Security Service (now Security Information Agency, or BIA) from the home of a Group America member. Two state security officers were charged, but the case has languished in the courts ever since.

In an indictment, prosecutors accused five group members of planning to kill senior government officials to “create fear among citizens and an atmosphere of inviolable power,” which would allow the gang to operate with impunity in a new political order.

Among Group America’s planned high-profile targets, prosecutors said, was the prime minister himself.

Months later, in March 2003, Đinđić was assassinated by a sniper.

Radonjić, by then no longer actively involved in gang leadership, was held by police for several weeks but was charged only with illegal possession of ammunition. The Đinđić hit was eventually credited to a rival gang, the Zemun clan. Radonjić died of natural causes in 2011.

In 1998, one year into Miljanić’s tenure as head of Group America, police in Peru arrested Jakšić and seized 1.22 kilograms of Group America cocaine hidden in spray cans destined for Miami. It was a taste of things to come.

In 2000, police in Bosnia seized a 164-kilogram consignment also linked to the gang.

By some estimates, the gang may have no more than 15 core members and perhaps 100 regular associates scattered across several continents but who travel internationally as needed. The group’s membership is fluid, often expanding by associating with other gangs in different regions and hiring freelancers for short-term work.

For example, Group America typically hires Serbian and Montenegrin sailors to smuggle shipments of less than 100 kilograms on commercial vessels and cruise ships sailing from South America to Europe, paying them on delivery. This approach reduces the cost of lost shipments and offers less incentive for authorities to spend time and money going after the group’s leaders.

In an assessment written by Italian investigators who tailed the gang in 2008 and 2009, detectives said they were impressed by its efficient management and ability to react quickly when threatened.

“The group is very strong economically and is able to create a base of operations in any city, but can also disappear or dissipate quickly in emergency situations,” they wrote.

“Spies Deserve to Die”

That appraisal came after police in Milan stumbled across something big while monitoring routine cocaine sales around Northern Italy.

Curious detectives followed a drug dealer to a meeting with Mileta Miljanić’s nephew, Mladen Miljanić, who was in Italy to prepare for a cocaine delivery.

The police followed Mladen Miljanić to a room in the Gran Duca di York, a stately boutique hotel, and traced his associates to short-stay apartments and hotel rooms across the city. They deployed hidden cameras, concealed microphones, and telephone taps to learn more.

What they saw and heard was staggering.

“These are hardcore criminals, very dangerous ones,” Marcello Musso, the prosecutor who handled the probe, told OCCRP in 2016. “They have their own paramilitary structure with a clear chain of command and a lot of weapons. They easily changed apartments, places where they lived, phone numbers. They acted like police would, which made the investigation much harder.”

The group’s activities were clearly profitable. One surveillance video shows Jakšić in a Milan hotel room, nonchalantly stacking more than 1 million euros on the table in front of him.

Over several months, the Italians filled out a picture of Group America as a “services agency” in the international drug trade, buying cocaine from Latin American producers and selling it to European wholesalers, but staying away from street-level sales.

The police surveillance also revealed a global network with distribution channels in the Americas, Africa, and Europe — and indications of friends in important places.

“I can say some serious information came to me,” said Musso, who died in a traffic accident last year. “Horrible information about corruption, about ties between narco-traffickers and the Serbian police.”

In early 2009, the Italians listened as Mileta Miljanić told Jakšić that a member of Serbian intelligence had tipped him off to a rat in Group America’s ranks. He named Milenko Lasković, also known as Laki, as the informant who told police about the group in 2001. The accusation fit: Lasković’s nickname, “Laki,” is a variation of “Lucky,” the English translation of Srećko.

It was heartbreaking news for Miljanić. Lasković was an old friend, though it didn’t mean he would overlook the transgression.

“He needs to be eliminated,” Miljanić told Jakšić in a telephone conversation.

After police in Buenos Aires seized more than $6 million worth of Group America cocaine, Miljanić told his second-in-command that he had grilled Lasković about past seizures and was unsatisfied with his answers.

The conclusion, overheard by police, was inescapable.

“Spies deserve to die,” Jakšić told Miljanić.

A year later, on the evening of January 18, 2010, Lasković was shot three times in the head while parking his Mercedes in a Belgrade suburb.

His murder remains unsolved.

Hiding in Plain Sight

On a surveillance tape transcribed by Italian police, Miljanić is heard offering life advice and tips on how to manage the gang and avoid arrest. His audience was Jakšić, whose looks, vices, and love of nightlife tended to attract attention.

“Everything should be relaxed, simple and normal,” Miljanić told him. “Zoran, please, take care. Don’t step into shit, and don’t take risks — and we will never be hungry. But if we fall, everything is over...”

Like the Dons of America’s traditional five New York mafia families, Miljanić himself leads a quiet life in New York. His primary residence appears to be the plain six-flat brick row house in Ridgewood, a working-class Queens neighborhood. His only known extravagance is a villa and acreage in Serbia.

Miljanić could blend easily into a crowd of accountants, but Jakšić — two meters tall, athletic, and with striking brown eyes — tends to get noticed.

While Miljanić stays close to home, Jakšić was a frequent flyer, often switching among 40 known false identities as he fronted for Group America around the world. At various times, authorities in Italy, Greece, Germany, and Argentina have issued warrants for his arrest.

For a decade, Jakšić’s primary base of operation was South America. Police in Peru say he did everything from negotiating deals with cocaine suppliers to handling payments and arranging shipments, often in bold and novel ways.

In Argentina he once planned to start a business that would smuggle cocaine to Spain in wine bottles. Police grew wise to the scheme and were about to arrest him but he fled the country.

Even when caught, Jakšić has managed to continue work and even gain advantage while in prison. Authorities say that after his 1998 arrest in Peru he made ample use of his prison term, forging strategic relationships and developing contacts with other inmates that later proved essential in the cocaine trade.

But Jakšić eventually fell hard, again in Peru. Police there arrested dozens of his associates and seized more than 854 kilograms of cocaine in a series of raids in 2016. Jakšić slipped away, likely thanks to a tip, but was arrested in the seaside city of Tumbes as he crossed the border from Ecuador.

While awaiting trial in Lima, Jakšić continued running Group America’s cocaine business from his cell at Miguel Castro Castro prison. In 2019 he was implicated in an escape plot and moved to the maximum-security Ancon 1 prison, where he is now serving a 25-year sentence for drug trafficking.

Closing in — and Slipping Away

Italian police in 2009 interrupted Group America’s drug delivery, but Miljanić and Jakšić left the country before they could be arrested. Fearing the gang’s ties to intelligence services and links to the U.S. would prevent international cooperation, authorities decided to wait for them to return.

As they waited, the Italians kept monitoring the gang’s cell calls. A senior law enforcement official told OCCRP the wiretaps picked up Miljanić negotiating with Russian mobsters about a daring new joint venture to smuggle cocaine from Venezuela by submarine.

That plan likely soured on May 31, 2010. Alitalia had informed police Miljanić would be flying from Belgrade to Thessaloniki in Northern Greece. He was arrested as he changed planes in Rome.

Musso, the prosecutor in Milan, told OCCRP that he pushed to have Miljanić charged as the head of an organized crime family, which could have added as much as 15 years to any sentence. But Musso couldn’t get Italy’s anti-Mafia prosecutor in Rome to go along.

Both the prosecutor and the senior Italian police official attributed Rome’s reluctance to pressure from the U.S., saying that Miljanić, a U.S. citizen, received an unusual number of visitors from the U.S. Embassy while in custody. Italian officials rejected OCCRP’s requests for prison visitation records that might confirm those visits.

But Alfredo Foti, an Italian criminal defense attorney and university researcher, told OCCRP that prosecuting Miljanić as an organized crime figure would have been difficult. The charge of “mafia association” is usually reserved for traditional Italian groups and requires specific criminal acts that were not associated with the smuggling operation that resulted in charges against the Group America leaders.

The case was eventually sent to Venice, where Miljanić was sentenced to seven years in prison and a 40,000 euro fine for drug distribution — punishment more fitting of a low-level drug operative than the head of a global trafficking network. On appeal, the sentence was cut by a year.

Limited prison records show Miljanić was sent to a prison in the northeastern Italian town of Tolmezzo, where he spent time picking fruit and gardening in a program called “A Garden to Escape.”

On May 6, 2014, Miljanić was granted “regime di semiliberta,” a kind of parole that allowed him to spend much of his time outside of prison, unsupervised.

He disappeared on August 25, 2014, 13 months before completing his sentence.

The Surveillance Court of Trieste, which had jurisdiction over the prisoner, told OCCRP it “acted according to the law’’ and notified both national and Venetian prosecutors about his disappearance, but said that nothing happened.

The Venice prosecutor’s office said only that it has no pending extradition request for Miljanić. It’s unclear why.

“You should not be surprised that someone who is sentenced in Italy walks free in the USA,’’ Musso told OCCRP in 2016. “Americans take care of their citizens, defend them. Not like Spain. They extradite criminals to us.”

While Italian police and prosecutors privately expressed dismay that they were unable to charge Miljanić as a major drug trafficker, only Musso would speak on the record.

“The court was responsible for this, not the police,’’ Musso said. “The courts were not capable of doing this right.”

“But it is important that we discovered this [Group America] phenomenon,’’ Musso added. “Still, we did something important — arrested him. But yes, we were not perfect.”

Miljanić remains a wanted fugitive in Italy, but is apparently safe from arrest unless he returns there.

Friends in Low Places?

The U.S. Department of State did not respond to written requests for information about Miljanić and Group America. But there are tantalizing clues that the gang does have an “in” with U.S. intelligence or law enforcement agencies.

One is the group’s close alignment with the Serbian secret police in the 1990s.

According to media reports, Sir Ivor Roberts, the U.K.’s ambassador in Belgrade from 1994 to 1997, testified in the international court in The Hague in October 2019 that the former head of the Serbian National Security Service, Jovica Stanišić, was a "secret agent of the Central Intelligence Agency.”

Roberts told the court he could say no more because the British government has "not allowed him to talk about these matters." He did not respond to an OCCRP request for an interview.

His description echoes allegations made by the Los Angeles Times in 2009 and in his own 2016 book, "Conversations with Milosevic."

Another clue is buried in federal court records in New York.

The docket for the federal court for the Southern District of New York shows that in October 2003, Miljanić, Jakšić, and Efrain Eduardo Rodriguez were indicted on a single charge of conspiracy to distribute cocaine. Assistant U.S. Attorney Neil M. Barofsky, a storied federal drug and financial crimes prosecutor, filed the case, which was immediately sealed.

U.S. grand jury indictments are commonly sealed until the accused is in custody, but unlike other sealed cases, USA v. Miljanić et al, was listed in the public docket. That listing, the only public record of the case, shows no indication that anyone was ever arrested, made a court appearance, or hired a defense attorney.

In December 2006, Barofsky went before a judge to unseal and immediately re-seal the indictment. There’s nothing in the docket to explain that unusual action.

Nearly 17 years after it was filed, the case remains on the books. Federal court, Drug Enforcement Administration, and Justice Department officials said they can’t comment on an open case.

Let’s Make a Deal

It’s not unusual for those accused of drug crimes to give up information in exchange for immunity from prosecution.

The handling of the Group America case contrasts starkly with Barofsky’s other work during his time with the U.S. Attorney’s elite International Narcotics Trafficking Unit. An OCCRP analysis of docket entries for dozens of cases filed in his last five years with the unit show court appearances, arrests, appointments of defense attorneys, convictions, sentences, or dismissal of charges in all other cases. Only the Group America case remains open and sealed.

Colombian Connections?

Barofsky is now a partner in Jenner & Block LLP, a top-shelf New York law firm. In July 2019 he told OCCRP he had only a vague recollection of the case.

He said he couldn’t recall why he went to court to open and then reseal it, a move he described as “odd.” Nor could he explain why the case remains active so many years later.

The former prosecutor volunteered that Rodriguez was a Colombian and said the case may have involved wiretap evidence linked to Cartagena or Medellin.

Three months after Miljanić, Jakšić, and Rodriguez were indicted, Barofsky became lead prosecutor in a long-running investigation that resulted in the indictment of 50 leaders of the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC), which was then financing guerilla operations by controlling much of Colombia’s cocaine production. Those indictments, still considered the largest narcotics case in U.S. history, were handed up in March 2006.

Though Rodriguez was likely Colombian and Barofsky said FARC was reportedly negotiating distribution deals with traffickers in Italy and Greece at that time, the former prosecutor discounted a link between the unusual handling of the Group America indictments and the FARC prosecutions. Evidence used in the FARC case came largely from Colombian defectors, he said.

“I’m sure we talked to other cooperators – I’m sure we did – but I don’t remember who they were,’’ Barofsky said. “They [Miljanić, Jakšić, and Rodriguez] might have been part of FARC, but the question is, did one lead to the other? They might have been related… but I don’t recall them being connected.”

Yet Barofsky didn’t dismiss the idea that Group America is protected by an intelligence agency, rhetorically asking, “Could somebody else be running them as informants?”

Asked about a specific U.S. law enforcement agency, Barofsky simply said, “Or somebody else.”

Arpad Soltesz (Jan Kuciak Investigative Center), Antonio Baquero (OCCRP), and Stelios Orphanides (OCCRP) contributed reporting.