Walter Glenn Primrose was ordered detained until trial at a hearing held Thursday in Honolulu, near where he and his wife Gwynn Darle Morrison were arrested and charged with assuming the identities of two children who died in Texas in the late 1960s.

The couple lived for decades under the stolen identities, and the bizarre tale has provoked international intrigue because prosecutors argue that Primose is a flight risk and could have been representing the interests of a foreign government. The U.S. Coast Guard confirmed Friday it is now part of a multi-agency look into Primrose and his two-decade career.

Prosecutors have provided scant detail about any espionage, and offered little about his career trajectory. But OCCRP has obtained photographic proof and confirmation from three people who knew Primrose as Chief Petty Officer Bobby Fort, when he was stationed in Alaska at U.S. Coast Guard Air Station Kodiak from 2013 to 2016.

There, the chief petty officer was attached to C-130 aircrews, whose mission includes long-range flights from Kodiak for patrolling and surveillance of the Bering Sea, the Arctic Circle and the Russian border.

A photo received anonymously by OCCRP shows a smiling CPO Fort in his blue operational dress uniform in a cart inside a cavernous air station hangar. He also appears in a photo accompanying a June 2014 posting on the U.S. Coast Guard District 17 Facebook page where he can be seen in a C-130 hangar. The event commemorated the visit of then-D17 commander Rear Admiral Dan Abel at Air Station Kodiak.

Primrose, as CPO Fort, also appears in a video posted on YouTube by the Make a Wish Foundation for a child with a rare blood disease who came to the air station to meet his heroes and take a helicopter flight.

The U.S. Coast Guard declined to provide a timeline of Primrose’s career.

“The U.S. Coast Guard and its investigative service are working with the Federal Bureau of Investigations and the Department of State to conduct a comprehensive investigation of Walter Glenn Primrose,” the service said in a statement to OCCRP. “The Coast Guard cannot release details about the case in order to uphold the integrity of the investigation.”

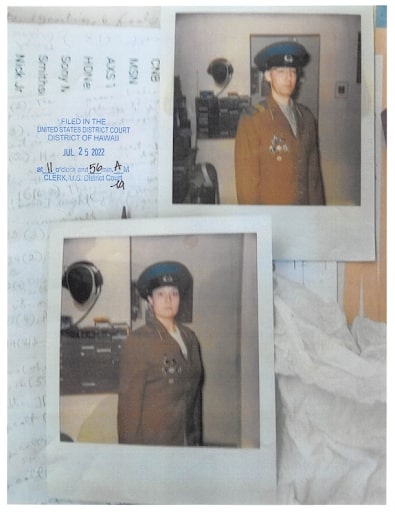

The case is an embarrassment for the U.S. Coast Guard, even if Primrose is not charged with espionage. He allegedly managed to serve under a fake identity for his entire career, moving up the career ladder and earning security clearances. Court documents suggest he was not found out by the service, but during the process of applying for Defense Department benefits. Walter Glenn Primrose and wife Gwynn Darle Morrison in what a U.S. government expert said were uniforms of the KGB, the Soviet spy agency. (Photo: Scanned handout, the U.S. Department of Justice)

Walter Glenn Primrose and wife Gwynn Darle Morrison in what a U.S. government expert said were uniforms of the KGB, the Soviet spy agency. (Photo: Scanned handout, the U.S. Department of Justice)

Prosecutors said Primrose, under the Fort identity, joined the service in 1994, retired in 2016 and worked with a defense contractor in Hawaii from retirement up until his arrest earlier this month. Prosecutors did not identify the contractor but said Primrose enjoyed a secret clearance with the U.S. Coast Guard and later with the contractor.

OCCRP has reviewed a document in which Fort represented himself as having started his U.S. Coast Guard career in Elizabeth City, North Carolina. There, he entered s an entry-level avionics specialist. Most of his career has been spent at the Air Station Barbers Point in Kapolei, just west of Honolulu, a point made by prosecutors.

Significantly, the U.S. government has not charged Primrose or his wife with espionage_ which led public defender Jerome Craig to tell a federal court judge on Thursday that prosecutors were fomenting “innuendo” and “speculation'' but had “provided almost no evidence at this point.”

If Russia sought to have a mole in Alaska, the air station at Base Kodiak in Alaska would be an ideal posting. Anyone with security clearance could learn where commercial and military vessels are at any time in the Bering Sea. It would also provide confirmation of what wasn’t being detected.

Air Station and Base Kodiak served as a Naval base in World War II. The U.S. Coast Guard operates a communications station in the region, its huge antennas able to pick up transmissions from as far away as Florida and the Philippines.

Although the Coast Guard is part of the Department of Homeland Security, the Defense Department operates a military launch facility for rockets and missiles less than an hour’s drive from Kodiak, where some advanced hypersonic missile technology has been tested.

Over the past decade, the melting polar caps have led the U.S. Coast Guard to provide greater coverage in areas such as Barrow, Alaska’s northernmost land point. It’s known as Operation Arctic Shield and comes as Russia aggressively expands both its military and energy reach in the Arctic.

Four people who knew Primrose as Bobby Fort in Kodiak confirmed that they had not yet been contacted by investigators. They are struggling to make sense of the allegations.

“My mind cannot wrap my head around it,” said a longtime friend of CPO Fort, who retired from the Coast Guard having served with him in Hawaii and Alaska.

Having known Fort for 15 years, the retired Coastie, as Guard members call themselves, said there are little oddities that now stand out.

“He was very frugal. It seemed like whenever he bought something, it was always with cash. It’s just something I noticed,” said the officer, who was so in disbelief of the allegations that he went to knock on Fort’s door to confirm he’d been detained.

Primrose under his alias Fort notably used a post office box in both Hawaii and Alaska instead of a home address, even though prosecutors said he owned two homes in Hawaii. The P.O. boxes make it harder to track him online.

One friend recalled how despite decades of experience, CPO Fort retired quickly and without a traditional ceremony. As a chief petty officer he had entered the first rung on the ladder of rank, giving him direction over subordinates. His post pays on average just under $70,000 annually, according to the employment website glassdoor.com.

The quiet chief petty officer largely kept to himself in Alaska.

“No reason to be remarkable. He was not bombastic or outgoing, he was sort of like me, just another introvert,” Lyle Refior, a Kodiak businessman and former U.S. Coast Guard member who said he met CPO Fort a few times.

OCCRP has pieced together some of Primrose’s life in Kodiak. He lived off base in at least two private residences, renting at one point from a direct supervisor for whom he also house sat.

By the time he reached Alaska, Primrose as Fort was in a more administrative position. Two people who knew him said he worked on data projects, often alone on evenings and weekends.

Primrose served in Kodiak while his wife Morrison stayed back in Hawaii, something members of the U.S. Coast Guard and other military branches call a geo-bachelor. Morrisson faces the same charges as her husband and prosecutors say she usurped the name of a dead infant Julie Lyn Montague.

Prosecutors allege the couple married under their real names, and later again in 1987 under their stolen identities. They were both born in 1955, meaning Primrose would have been too old to enlist in 1994. He enlisted under the identity of someone born 12 years later than him in 1967.

Prosecutors have not explained why the couple would take on new names and have virtually no footprint under either identity. They apparently did not use their stolen identities to swindle or defraud or to cover up a past crime. They appear to have lived unremarkable lives, but prosecutors allege they told family in the late 1980’s that they were going into a witness-protection program, later explaining away their new names as a security measure.

Assistant U.S. Attorney Wayne Myers acknowledged Thursday they didn’t pose a conventional risk to their community but warned Primrose “may have some troubling foreign connections.” He repeated to the court that Primrose failed to report travels to Canada, which was required of his security clearance and described Morrison as having had anti-government, anti-military views.

Authorities seized invisible ink, what appeared to be coded documents and maps of military bases when Primrose’s home near Honolulu was raided, prosecutors told U.S. District Judge Rom (cq) Trader.

When left alone during the raid but recorded, the couple appeared to communicate to each other in manners “consistent with espionage,” said Myers, the prosecutor.

But the U.S. government stopped short of calling Primrose a spy. The quiet avid hiker showed little emotion at his detention hearing. He was described by friends as polite to a fault, a trait on display Thursday when he thanked the judge for his time at the end of his telephonic detention hearing.