A Montenegrin court recently adopted an opinion written by the country’s most influential judge that would allow some government critics and civil society advocates to be silenced without legal recourse.

Vesna Medenica, the Supreme Court judge who issued the legal memorandum, wasn’t involved in any of the lower court cases affected by it. But she decided to make her views known regardless.

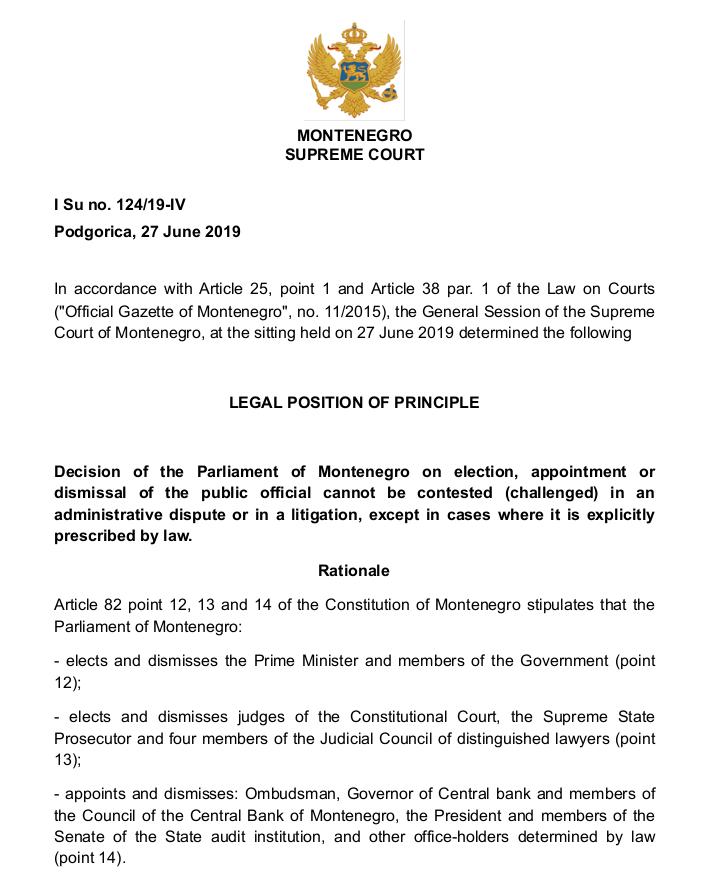

Her unsolicited opinion, promptly endorsed by the Supreme Court in June with no open debate, could set a precedent that Montenegrin courts have no right to challenge parliamentary decisions to dismiss public officials — even if they were fired for political reasons.

If Montenegro’s courts systematically decide they can't challenge such dismissals by Parliament, it would create “a serious crisis of rule of law,” said Adam Foldes, a legal adviser with Transparency International.

The Nov. 5 ruling — the first in which Medenica's opinion was applied — affirmed that a court could not challenge Parliament’s right to fire a media-freedom advocate. Several similar cases are pending. They include a case against Irena Radovic, a whistleblower who worked for the Central Bank, as well as other civil society advocates appointed to watchdog roles over government institutions.

Goran Djurovic was dismissed from his position as a civil society representative on the council overseeing Montenegro’s public broadcaster in December 2017. His case has been making its way through the country’s court system for nearly two years.

He said he was disappointed — but not surprised — that a lower court had uncritically adopted Medenica’s views.

“I was hoping that the judge could resist pressure to rule against me,” Djurovic said.

The new ruling, which ordered him to pay 750 euros to cover the government’s legal costs, not only quashed his previous legal victory, but means he will be banned from holding any public position for the next four years.

Critics say Djurovic’s case sets a dangerous precedent that could undermine Montenegro’s efforts to fight corruption and reform its judiciary — conditions required to join the European Union.

The EU ambassador in Montenegro, Aivo Orav, said the verdicts could influence how quickly the country moves toward joining the union.

“We will continue to monitor developments in this area in the context of the accession negotiations, the pace of which will continue to be determined by Montenegro’s progress in the area of rule of law,” Orav said in an email.

In response to questions submitted by OCCRP, Medenica’s cabinet denied that her opinion, if adopted by the courts, would eliminate legal recourse for public officials dismissed by Parliament.

However, the cabinet did not explain how dismissed public officials would be able to bring a case to court. Medenica’s opinion clearly states that “dismissal of the public official cannot be contested (challenged) in an administrative dispute or in a litigation.”

“The courts are undisputedly committed to the repression of corruption,” the cabinet insisted.

Silencing Whistleblowers

Montenegro Supreme Court Judge Vesna Medenica (Supreme Court of Montenegro) Cases currently under review using the legal standards put forward in Medenica’s opinion include one involving Vanja Calovic Markovic, the head of MANS — OCCRP’s member center in Montenegro — who was removed from a council monitoring the country’s anti-corruption agency.

Montenegro Supreme Court Judge Vesna Medenica (Supreme Court of Montenegro) Cases currently under review using the legal standards put forward in Medenica’s opinion include one involving Vanja Calovic Markovic, the head of MANS — OCCRP’s member center in Montenegro — who was removed from a council monitoring the country’s anti-corruption agency.

Another key case involves Radovic, who was dismissed from her position as a vice governor at the Central Bank in July 2018.

She filed a wrongful termination lawsuit, which the government repeatedly challenged. Judges found in her favor several times, including a ruling in late September that the government appealed, citing Medenica’s opinion. The High Court is expected to decide on that appeal any day.

Radovic said she was “appalled” by the ruling against Djurovic. She said she hoped the High Court judge overseeing the government’s appeal of her case would not reverse previous verdicts in her favor.

Radovic told OCCRP she was fired after refusing to sign off on what she said were corrupt and illegal practices at the Central Bank, headed by Radoje Zugic, a powerful member of the Democratic Party of Socialists (DPS), which has ruled Montenegro since the multi-party system was introduced in 1990.

She said she was harassed and bullied during her time in the job, and she filed a lawsuit against Zugic in response. He then filed a criminal complaint against Radovic, claiming that she had revealed a “business secret” to the court when submitting documents to support her suit. Prosecutors rejected Zugic’s complaint on lack of evidence.

“In retaliation, he decided — and the ruling party agreed with him — to get rid of me,” Radovic said.

It was then, she said, the DPS-dominated Parliament dismissed her. Radovic filed the wrongful termination suit and the courts rejected Zugic’s allegations that she was incompetent and had revealed a business secret.

“No court, nor anyone else, ever challenged the fact that I was dismissed on false allegations without evidence and because of a criminal complaint, which was rejected as unfounded after my dismissal,” Radovic said.

A High Court ruling on her case adopting Medenica’s legal opinion would “show to the citizens that the ruling party strongmen are above the law and judicial system in Montenegro,” she added.

The Central Bank communications directorate told OCCRP that Zugic and four other officials had denied in court Radovic’s allegations of corruption. The bank said it would “not have any further comment until the valid end of the court dispute.”

Radovic has support from some corners in Parliament, including Aleksandar Damjanovic, who sits in opposition as an independent.

Damjanovic, a former chair of Parliament’s finance committee, said efforts to silence Radovic illustrate the collusion between government and the judiciary that occurs “when they need to protect the so-called state interests or political interests.”

Foldes, of Transparency International, said that more court rulings adopting Medenica’s legal opinion against public officials who say they were wrongly fired would send a chilling message to potential whistleblowers.

“If these individuals can prove they were dismissed because they resisted corruption, then the dismissals will discourage others to speak up,” he said.

EU Commitments

Legal opinion by Supreme Court President Vesna Medenica (Cabinet of the President of the Supreme Court of Montenegro) Radovic’s case and the others under review also raise questions about Montenegro’s pledge to align its judicial system with EU norms.

Legal opinion by Supreme Court President Vesna Medenica (Cabinet of the President of the Supreme Court of Montenegro) Radovic’s case and the others under review also raise questions about Montenegro’s pledge to align its judicial system with EU norms.

Montenegro, a former Yugoslavian republic, is a party to the European Convention on Human Rights, which requires that all citizens have access to the court system and to receive a fair trial, Foldes said.

That principle was confirmed by the European Court of Human Rights in a 2016 verdict in favor of the president of the Supreme Court of Hungary, who was unlawfully dismissed from his position.

“These rules and cases must be known to the courts of Montenegro,” Foldes said. “That's why any legal opinion stating the contrary is quite puzzling."

In its statement, the Supreme Court president’s cabinet said it had taken into account European Court of Human Rights case law when considering Medenica’s legal opinion, and it said that courts in Croatia and Slovenia, EU member states that were also once part of Yugoslavia, adopted similar practices.

Djurovic, the former media watchdog who lost his case last week, said the EU should take action against Montenegro to prevent it from any further backsliding on its commitments to the rule of law.

For example, he said, the EU could enact the “balance clause,” allowing it to block Montenegro from moving forward in the accession process until it makes sufficient reforms on the judiciary, justice, and fundamental rights.

“You invest billions in the region without any serious action to protect that investment,” Djurovic said of EU efforts to promote democracy. “You could do more to protect investment in democratization.”

The EU has been negotiating with Montenegro on these reforms for five years. The same negotiations with Croatia took only one year.

“We are just pretending we are living in a democracy,” Djurovic said. “The government plays the game very well and the EU plays it very badly.”