A week before the parent company of Cambridge Analytica filed for bankruptcy, one of its employees opened a UK firm that has since been providing similar “behavioral modification” training to clients including the Canadian and Dutch militaries.

Strategic Communication Laboratories (SCL) Group, Cambridge’s parent company, drew on psychological and social science research to distill techniques aimed at manipulating group behavior.

For almost two decades, SCL sold its services to clients around the world. They included political parties trying to sway voters in scores of countries, and the British and American militaries attempting to influence populations and insurgents in conflicts such as Iraq and Afghanistan.

But SCL did not survive its firm’s best-known campaigns: Its subsidiary, Cambridge Analytica, sparked a scandal due to its involvement in Donald Trump’s 2016 U.S. presidential campaign, and questions were raised over the role of Cambridge Analytica and an affiliate in the successful movement the same year for Britain to leave the European Union.

Cambridge Analytica was subsequently found to have misappropriated data from Facebook, which it used to build profiles of about 87 million users. The scandal forced the entire group of companies to file for insolvency on May 1, 2018.

Just a week earlier, on April 25, SCL’s director of operations, Gaby van den Berg, formed a new company, Emic Consulting Limited, UK company records show. Since then, van den Berg has been marketing Emic’s services — training courses based on those developed by SCL — to military clients in Canada and her native Netherlands. The founder of SCL, Nigel Oakes, has also lectured for Emic’s courses.

Van den Berg declined to comment for this article.

The fact that Emic was able to rise from the ashes of SCL while the Cambridge Analytica and SCL debacle was still under investigation shows that governments have not learned the lessons of 2016.

It's vital that scandals such as this are properly investigated to protect against unethical business practices, conflicts of interest, security issues and data rights infringements. And governments must improve procurement processes to prevent the hiring of companies spun off from firms under active investigation.

So far, this is not happening. Governments are failing us. Such firms continue to provide training, or engage directly, in tactics to influence the behavior of citizens.

As if to underscore the negligence of U.K. authorities, the country’s Information Commissioner’s Office told me late last month that it had halted its investigation into data misuse, without making a public statement. It says it is no longer publishing a promised report on the content of SCL and Cambridge Analytica servers.

Military Contracts

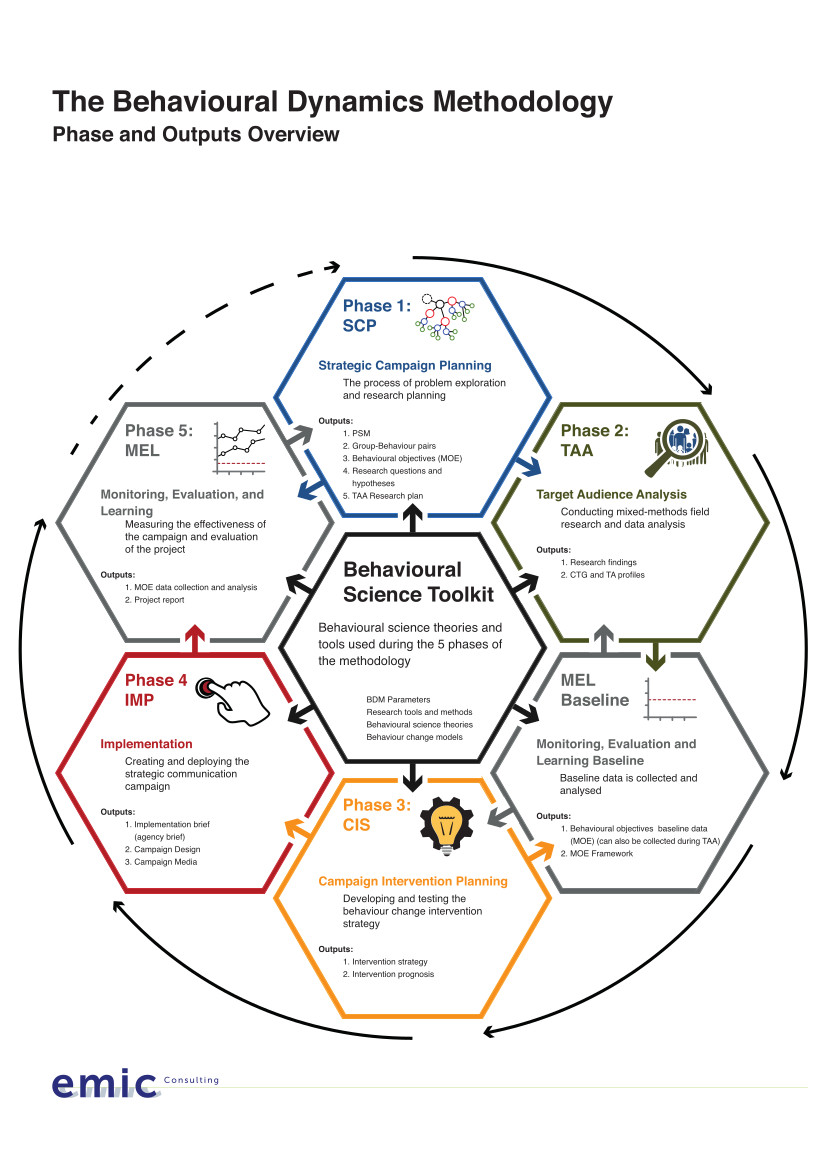

A diagram of Emic's training methodology. (Credit: Anonymous)The training program Emic is selling is a direct descendent of SCL’s branded “Behavioural Dynamics Methodology.” It promises to help its military clients analyze and profile groups to find the best strategy to effectively influence a target audience’s behavior.

A diagram of Emic's training methodology. (Credit: Anonymous)The training program Emic is selling is a direct descendent of SCL’s branded “Behavioural Dynamics Methodology.” It promises to help its military clients analyze and profile groups to find the best strategy to effectively influence a target audience’s behavior.

These claims have proven persuasive to some governments.

In The Netherlands, Emic hit the ground running soon after its incorporation, securing two military contracts in 2018. Other companies were not even given the opportunity to compete for the contracts “due to the unique specification of the training” sold by Emic, according to the Dutch Ministry of Defense.

These included a two-week “practitioner course” that provided training at a cost of 27,846 British pounds ($35,719). Emic also earned 27,000 euros ($31,456) from the Dutch military for research in Mali to investigate to what extent local people were prepared to reveal to soldiers the locations of IEDs. In 2019, Emic was also paid 263,000 euros ($306,442) by the Dutch military for a six-week Behavioral Dynamics Methodology course.

Emic has also found a client in the Canadian Armed Forces, which hired the company in 2019 to to help soldiers “better identify and understand key audiences, thus resulting in communications campaigns that are more customised and effective,” the military confirmed in an email.

This “actor and audience analysis training course” trained just 20 personnel at a cost of CDN$615,285 (about US$460,000).

Just months later, the government began investigating allegations that its military conducted unauthorized operations to influence the public during the coronavirus pandemic.

In one of them, likened to a “propaganda campaign” by military insiders who spoke to the Ottawa Citizen newspaper, the Canadian Forces proposed using military vehicles with loudspeakers to maintain order amid the pandemic, along with “village assessments” throughout the country. Another operation involved a military intelligence unit that mined social media profiles for data, the Citizen reported.

Amid the scandal, the Canadian military last month awarded yet another contract to Emic Consulting, this one for $578,285, for more such training.

It’s not even clear that these methods work as advertised.

Behavioral Dynamics Methodology was twice analyzed by the British Defense Science and Technology Laboratory to determine whether it was effective, but the results were inconclusive, according to documents obtained through Freedom of Information legislation.

(Click to read the 2011 evaluation and the 2014 evaluation.)

Still, even ineffective influence campaigns can have major — and unexpected — impacts on audiences or situations. SCL had real-world impact worldwide.

The company has been accused of using Behavioral Dynamics Methodology to unethically manipulate election campaigns in countries including St. Kitts. SCL set up a sting operation in the Caribbean nation to offer the opposition leader a $1M bribe. He was covertly filmed accepting the money, and SCL then broadcast this footage at a rally.

Van den Berg, Emic’s founder, worked for several months on the same campaign, according to a senior former SCL employee. However, Van den Berg has denied having been involved in controversial campaigns, telling Dutch journalists: “I have never had anything to do with such practices.”

“Occasionally the solution is not communication but intervention — for example, the ‘discovery’ of an opponent’s corruption,” SCL wrote in a 2010 pitch to Kenyan politicians. “SCL will develop and implement whatever combination is needed to achieve the result.”

It was later hired by Kenyan President Uhuru Kenyatta to work on his 2013 and 2017 election campaigns. The SCL subsidiary Cambridge Analytica was accused of having “poisoned Kenya’s democracy,” including stirring up tribal tensions and airing “apocalyptic” attack ads painting Kenyatta’s opponent as violent and dangerous.

Oversight Needed

Emic has touted its employees’ experience working for SCL when selling its services to governments. The courses Emic now offers appear to be directly derived from those developed by SCL, which were first provided for Singapore’s military in 2008.

SCL’s work there included a “live research project” aimed at increasing support for national service and commitment in the military. Van den Berg was “a major part of the Singapore training course” and further developed the methods established by Oakes, according to Lee Rowland, an SCL colleague.

The course was a success and Singapore’s military invited van den Berg and SCL back again the following year. Documents show she led several training sessions there, on topics including influencing “campaign target groups” and “motivations.” (Singapore’s military declined to comment.)

SCL’s training for Singapore drew on its traditional behavioral dynamics methodology, not the “big data” approach championed by Cambridge Analytica. But the country was later linked to the Cambridge Analytica data scandal when Singaporean psychologists and academics working with the government were revealed to have access to the Facebook user data obtained by CA.

Journalists raised concern about SCL’s involvement as the government there has rolled out an “information dominance” approach toward its citizenry. Singapore has a poor human rights record related to privacy and media freedom, currently ranking 158 out of 180 in the World Press Freedom Index.

Rowland said what they were working on in Singapore back in 2008 seemed “benign at the time,” but later he started to feel “moral concerns” about it and remained conflicted. When Emic started up, he agreed to work for them. But he stopped working for the firm earlier this year.

“I don’t have any moral concerns about the training,” he told me, “but I worry more about how BD methodology is used and by whom. It needs regulation.”

He also worried that SCL’s “train the trainer” program would put information warfare methodologies into unscrupulous hands, with no oversight.

Emic is not the only firm to successfully spin out of the SCL-Cambridge Analytica meltdown. Former employees have created a number of other companies and little is known about what they are doing, and for whom.

It is deeply concerning that governments continue to hire new companies that train new influence professionals, using the same old methods and run by the same figures. This underscores the need for more rigorous investigations, greater transparency and stronger governance of the global influence industry, especially where it touches on defense.

And without proper regulation and oversight of companies that draw on personal data to modify behavior, it is just a matter of time before the next Cambridge Analytica-type scandal unfolds.

Dr. Emma Briant is an Associate Researcher at Bard College. She submitted evidence to multiple investigations into disinformation and became central in exposing wrongdoing by SCL and Cambridge Analytica in 2018. She is the author of the upcoming book “Propaganda Machine: Inside Cambridge Analytica and the Digital Influence Industry.”