RIGA, LATVIA – Tourists flock to Riga’s iconic Central Market to snap photographs of fresh produce and sample this Baltic nation’s famous smoked fish and fresh cheeses. Locals come for daily shopping.

Trade here is mostly orderly and well-regulated, fitting for a symbol of the Latvian capital that attracts up to 100,000 visitors per day and has attained Unesco World Heritage status.

But in an area of the market cynically nicknamed “Shanghai” by administrators, a different kind of commerce reigns, with sellers of illegal cigarette vying for space with sleeping vagrants and loitering teenagers.

And here, vendors hawk wares that are far from fresh.

These poorly regulated stalls have different names, but they sell the same products: crackers, cookies, chocolates, canned tomatoes, and other packaged goods. Some are counterfeit. Others show expiration dates falsified to extend their salability.

Two companies run by the same people operate all of the shops. Over the past decade, the companies have received dozens of fines and warnings from Latvia’s Food and Veterinary Service (FVS) over sale of out-of-date food. They have also seen hundreds of kilograms of foodstuffs confiscated in repeated raids.

But they are allowed to continue doing business in the Central Market owned by the municipality of Riga. One market administrator laughed off the issue as trivial, while police say they do not know if faking expiration dates is even a crime.

Selling expired food is against Latvian law and violates the market’s tenancy agreement, but it is punishable only by a fine, and violations are not systematically tracked by Central Market administration.

Cheap and Old

The discount dealers of Central Market don’t try to hide the fact that their wares are cheap — on the contrary, they flaunt it.

The shopkeepers take only cash, which they stuff into fanny packs instead of cash registers. They display their wares in old cardboard boxes, or heaped haphazardly on plastic trays. Astonishingly low prices are heralded with large green stickers plastered onto boxes and jars. A package of meringues from the local brand Laima, for example, costs 3.59 euros at a nearby store, but just 1.50 here. A marzipan bar priced at 2.45 euros elsewhere costs 1.50 here.

Many of the goods lack product information in Latvian, as required by law, and some are from product lines produced exclusively for supermarket chains outside Latvia, such as Lidl and Kaufland.

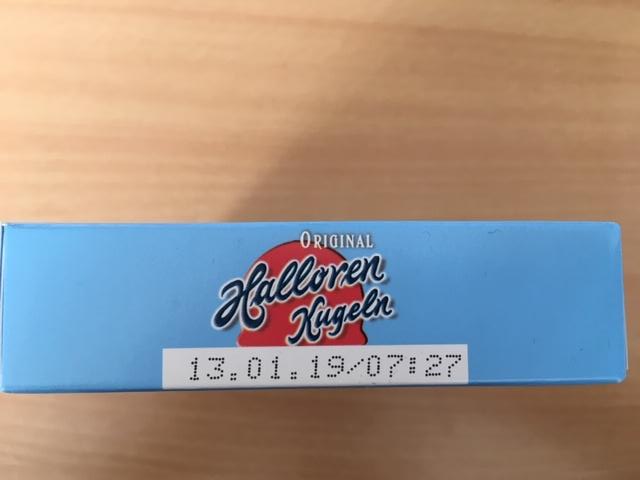

Fake label (Photo by Baiba Kļava) One package of German-made marzipan even bears a price tag from the supermarket chain Denner. A package of chocolate shows a label for German discount brand Netto Marken-Discount. Representatives of both Kaufland and Netto, as well as seven other manufacturers whose products are sold at the stalls, confirmed that they were not meant to be distributed in Latvia.

Fake label (Photo by Baiba Kļava) One package of German-made marzipan even bears a price tag from the supermarket chain Denner. A package of chocolate shows a label for German discount brand Netto Marken-Discount. Representatives of both Kaufland and Netto, as well as seven other manufacturers whose products are sold at the stalls, confirmed that they were not meant to be distributed in Latvia.

But the most striking characteristic of the goods are scratches, ink spots, slapped-on labels and other signs of tampering with printed expiration dates.

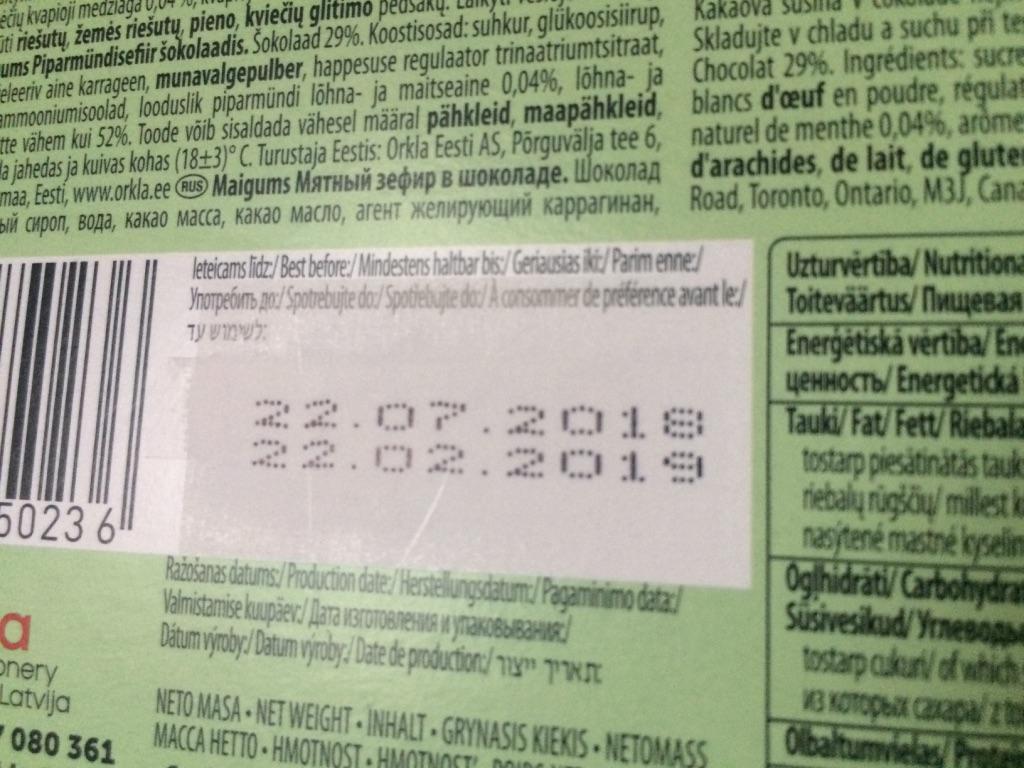

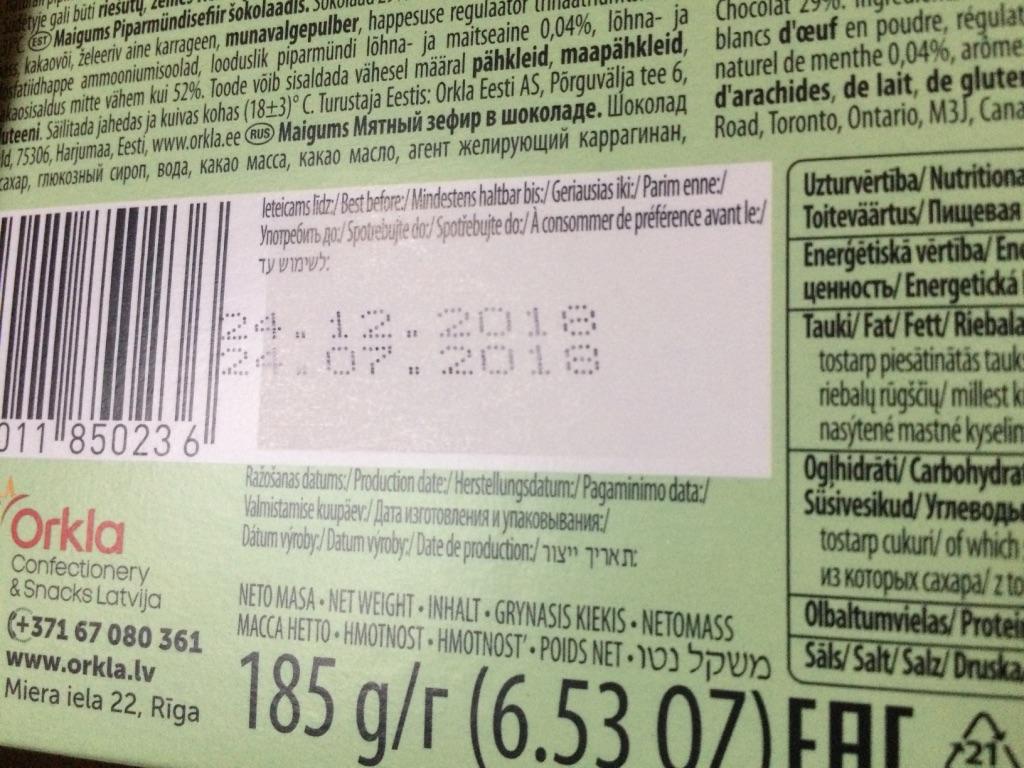

Original label (Photo by Baiba Kļava) Most of the goods examined by a journalist at the seven discount stalls in Central Market, as well as three others nearby, bore these telltale signs of tampering. On plastic or metal containers, the original expiration date is often erased, with a new date printed on. On paper, it is more common to plaster a new sticker over the old one. Sometimes the old date is gouged off. Although barely visible to the naked eye, traces of the process remain: a smidgen of glue, or a slight depression.

Original label (Photo by Baiba Kļava) Most of the goods examined by a journalist at the seven discount stalls in Central Market, as well as three others nearby, bore these telltale signs of tampering. On plastic or metal containers, the original expiration date is often erased, with a new date printed on. On paper, it is more common to plaster a new sticker over the old one. Sometimes the old date is gouged off. Although barely visible to the naked eye, traces of the process remain: a smidgen of glue, or a slight depression.

Multiple manufacturers confirmed that goods bearing their name had been tampered with.

Lineta Miksa, a representative of the Orkla Confectionery and Snacks brand, said meringues offered at the stalls are counterfeit. The evidence: a production date on a Sunday, when Orkla plants are always closed, and a claim of a seven-month shelf life when Orkla limits its products to five.

Two Are One

Some discount food outlets display orange signboards that read “Food t40°” or “Drinks t40°”. One is branded under the name “Lats,” a large local franchise. Others have no signs at all.

But registration information displayed at each stall shows all are owned by either Solovs or Fildaros.

For ostensibly separate companies, Solovs and Fildaros have much in common.

Although they have different named owners, they were created in 2001 within two weeks of each other, and for years shared the same phone number in the business registry. They are headquartered in adjacent buildings and share storage near Central Market.

The same middle-aged men cart goods from storage facility to the stalls of both companies. All Solovs and Fildaros outlets sell the same products at the same prices, and some use similar signage.

The companies also share another unusual characteristic: Huge sales but tiny profits. Solovs’s net annual sales approach 1 million euros but it reports only 1,000 euros in profit. Fildaros does slightly better: 2,000 euros of profit on 500,000 euros in sales.

Līga Leitāne, a lecturer at the University of Latvia’s Faculty of Business, Management and Economics, said tiny profit with high turnover can signal tax fraud, especially in cash-only businesses.

“If cash registers are not used and not all transactions are listed, there might appear a situation when not all the income get registered,” she said.

While not speaking specifically about Solovs and Fildaros, she said there are generally two ways for foreign products to appear in Latvian markets for lower prices than in their home countries: smuggling and tax evasion.

Sergejs Filipovs, 44, is general manager of both companies. While supervising the loading of boxes in the shared warehouse one recent morning, he denied any falsification of expiration dates.

“We have no such thing,” he said. “We have taken care of everything. It’s all good now.”

He said the companies keep prices low by dealing in products close to their expiration dates. When asked if Solovs illegally imports goods from abroad, Filipov escorted the the journalist from the warehouse and followed her through the market, loudly warning vendors not to talk to her.

Latvia’s business registry shows that a woman named Ludmila Filipova, 66, owns Solovs, while Olga Afanasjeva, 44, owns Fildaros. Filipova could not be reached for comment, while Afanasjeva declined an interview, saying that questions about the origins of the food in her shop and whether her sales were properly registered were “stupid.”

“That is nonsense,” she said angrily. “In my business, sales occur; I buy goods and sales are put through a cash register.”

No Consequences

Both companies have been slapped with numerous fines by the FVS for selling old food. Since 2013, Fildaros has been fined ten times by FVS, while Solovs has received a whopping 50 fines since 2009. All were for selling foods with inappropriate marking or already expired foods.

Why are they still in business?

Partly because the fines are relatively low — just 35 euros from the Central Market and from 15 to 700 euros for a Food and Veterinary Service violation — and there are no provisions in either the market’s bylaws or Latvian law to shut down repeat offenders.

The FVS admits it cannot do much about the sale of remarked goods unless they catch vendors in the act or find equipment used to alter dates.

Fake label (Photo by Baiba Kļava) “The service is actually powerless, unless we catch someone doing it in that moment,” said Iveta Grīnberga, senior expert at FVS’s Food Distribution Monitoring Division.

Fake label (Photo by Baiba Kļava) “The service is actually powerless, unless we catch someone doing it in that moment,” said Iveta Grīnberga, senior expert at FVS’s Food Distribution Monitoring Division.

Raimonds Tukišs, deputy head of the Riga FVS, concurred that there is no legal way to shut down the stalls because selling out-of-date food is a minor offense.

And what about altering expiration dates?

“Expiration date forgery ... Is it a crime? I can’t really say. I’ll have to think about it,” said Egils Ezis, chief of the Riga Latgale District Police.

Original label (Photo by Baiba Kļava) In fact, there is no law against expiration-date tampering.

Original label (Photo by Baiba Kļava) In fact, there is no law against expiration-date tampering.

Tukišs said most products are safe if eaten shortly after the expiration date. Still, there are risks, especially with filled chocolates that may be tainted by salmonella.

Although there are questions about whether the shops sell illegally imported goods, neither the FVS nor the police see this as their responsibility.

Tukišs said it is not the job of the police, not FVS, to determine the origin of the goods. Ezis, meanwhile, said the police can act only if someone files a complaint alleging a crime such as tax evasion or fraud.

Still, selling old food is clearly a violation of the Central Market’s tenant rules. Given the extent of the fines Solovs and Fildaros have amassed, why are they allowed to continue doing business?

Vladimir Kazarinov, head of the market’s Organization of Trade Department, said a tenant’s contract can be terminated for repeatedly violating market rules, but because the market has no system to track violations, it impossible to determine which companies are repeat offenders.

Marija Piščikova, the head of the market’s Sanitary Department, said she is aware that Solovs and Fildaros frequently incur violations for selling expired food. But she said she considers it a minor issue.

She said her department is mainly concerned with the safety of raw goods that could spoil, not packaged wares.

“We have no concern about Solovs,” she said. “I take it [expired food] along the way, throw it in the trash, and that is all.” Asked by a journalist why she simply throws the food away rather than writing an official report about multiple violations at the stall, she replied, “You can complain about me to the UN.”

Food confiscated by inspection (Photo by Baiba Kļava)

Food confiscated by inspection (Photo by Baiba Kļava)

An Inspection

After being asked for comment on falsified goods, the FVS arranged an inspection of three Solovs food stalls in late February.

Two inspectors wearing disposable green coats washed their hands and began to comb through one stall’s wares shortly after 10 a.m. Almost immediately they found suspiciously labeled packages plastered with stickers covering up older expiration dates, which they dumped into large, green plastic bags.

Zoja, a woman working at one of the stalls, spoke no Latvian. In Russian she said she had only worked there for two weeks and knew nothing about re-labeling.

“We receive what is brought from the warehouse,” she said. “We do nothing. They supply us with everything.”

All told, 285 kilograms of food were confiscated from the three Solovs stalls, and 1,900 euros in fines — almost as much as the company’s declared profits for the past two years combined — were issued.

But no stalls were closed. On a recent day, “Shanghai” was as crowded as usual, thronging with teenagers from nearby schools and adults looking for a bargain.

One shopper, Dace Liepiņa said she often visits the stalls because they’re easier to navigate and the prices are better than at supermarkets.

“The offerings are very wide,” she said. “Why not use it as an opportunity to save some money?”

But Liepiņa said fake labels give her pause.

"I wouldn't want to buy an old product because I don't know exactly how old it is — maybe it's a month, maybe it's a year, maybe it's even more,’’ she said. “Thank God everything has been fine so far, but you can never know."