I knew I had an unusual story on my hand, but I didn’t guess how unusual, when I met the man accused by Russian law enforcement of leading one of the deadliest gangs in the country’s rich criminal history.

We agreed to meet next to Vienna’s Grand Hotel in October 2016. On a sunny fall day, he waited on the street by the entrance — tall and almost bald, dressed in jeans, a tight black shirt, and a leather jacket. “Aslan,” he said.

That was my introduction to Aslan Gagiyev, who had created a criminal group, called the Family, which is accused of committing 60 murders. But by the end of our conversation, I understood that Gagiyev wasn’t just a gang boss. He was a key player in the symbiotic relationship that binds Russia’s law enforcement apparatus and its criminal underworld.

Chapter 1

In which I meet Big Brother and agree to write about him if he’s extradited or killed. He turns out to be more than just a killer.

“Killer No. 1”

Gagiyev, or Dzhako as the Russian media likes to call him, picked a good place to meet — one where it would be easy to avoid any surveillance. We went into the hotel, walked through the lobby and out the back door. Then we strolled around the neighboring alleys before reaching a small café. He ordered tea because he doesn’t drink. I ordered beer because I do.

“My nickname, Dzhako, was invented by the cops, so it would look more criminal,” he said. “That’s what a very close friend from my youth used to call me. He later betrayed me. But [back home], everyone knows me as Brother or Big Brother.”

Gagiyev was arrested in Vienna in January 2015 on an international warrant, after which he was released on bail as he battled his extradition back to Russia.

The authorities there say that Gagiyev is an organized crime figure who formed the Family, an elite murder squad with over 50 members, in 2004.

“As a result of its criminal activity, 60 people — including law enforcement officers, officials on republican and city levels, businessmen, and others — were killed in Moscow, the Moscow Region, and the Republic of North Ossetia-Alania. … 23 members of the criminal organization have been sentenced to long prison terms, including two to life terms,” the Investigative Committee, Russia’s top law enforcement body, wrote in a press release about the extradition.

The members of the Family called each other Brothers, and did what they considered to be good deeds, like killing those who “get in the way of people’s lives in North Ossetia.” On one occasion, they went after the leaders of a kidnapping gang operating in the republic.

But criminals were not their only victims. The Family also took out high-ranking officials and bystanders.

Among their high-profile victims between 2008 and 2012 were Vladikavkaz Mayor Vitaly Karayev, North Ossetia’s vice-premier Kazbek Pagiyev, former KGB official Andrei Burlakov, and Investigative Committee officer Alexander Leonov.

Unremarked upon in the press releases are the many law enforcement officials who can be counted among the Family’s members. Also unmentioned is the fact that the Family appears to have been funded by a Russian state company.

After five hours in the café with Gagiyev, I left with a new view of my country’s recent history. In the most improbable way, he had participated in 25 years of some of the country’s most memorable events: Ethnic conflicts in the North Caucasus, the rise of a kleptocratic state that collaborated with criminals, the rescue of the hostages in the Beslan elementary school attack, the war in South Ossetia, and many others.

Since I first met him, Gagiyev and his lawyers had been trying to prove to the Austrian court that he has not been involved in any murders; that his criminal prosecution was politically motivated because of his popularity in his native region of Ossetia; that he was being hunted by corrupt officials and siloviki (a Russian term referring to political members of intelligence, law enforcement or the military) to whom he has paid bribes for many years; and that in Russia he has been tortured and would be tortured again, or even killed.

None of that impressed the Austrian court. On June 20, Gagiyev was extradited to Russia.

List of Patrons

Gagiyev’s High-Level Connections

The high-level officials listed as being connected to Gagiyev include:

Alexandr Totoonov (Totoonti), formerly the representative of North Ossetia-Alania in Russia’s Federation Council and currently first deputy head of the republic’s parliament;

Sergei Takoyev, former chairman of the government of North Ossetia-Alania;

German Shtadler, chief advisor to the State and Legal Directorate of the President of the Russian Federation between 2005-2006; former prosecutor of North Ossetia-Alania, Karelia, and the Leningrad Region; and is now director of the St. Petersburg Institute of Law, an institution of the General Prosecutor's Office.

Arkady Gabalov, former deputy head of the Investigative Department of the Investigative Committee in Northern Ossetia. In 2016, Gabalov was convicted by a Moscow court for trying to arrange the resignation of the Minister of Interior of North Ossetia at the Family’s behest.

Reporters reached out to these people about their alleged ties to Gagiyev. Gabalov and Shtadler could not be reached for comment.

Alexander Totoonov said that Gagiyev has never been his friend, acquaintance, or even a “close connection.”

“Ossetia is very small, and everyone who lives here can have common acquaintances and can meet at different events without even knowing each other. That is why insinuations about false closeness are possible to make for everyone in such a small nation,” he said.

Sergei Takoyev confirmed to reporters that he knew Gagiyev. “We met about 10 years ago,” he said. “Of course we don’t have any ‘close connections’ as people from the law enforcement have written in various cases. By that time the government was selling its share in the airport in Beslan.”

Takoyev explained that he met Gagiyev, who was using a different name, as a potential buyer of the Beslan airport. “It seemed that he cared a lot about North Ossetia and the conditions in which its people lived. I heard from people who survived the terrorist attack in Beslan that Gagiyev helped them a lot. … I was surprised when I saw articles about his ‘other life.’”

“As far as I recall, his partners won the [airport] tender,” said Takoyev.

Now his home country casts Gagiyev as an outsider, a cold-blooded murderer who must be put away to protect the public. More accurately he could be described as an integral part of the Russian state, who has fought its wars and to whom high-ranking officials turned for help. Among the materials of the criminal cases against the Family is a report which lists some of the officials connected to Gagiyev. It includes parliamentarians, prosecutors, and police officials (see box).

But this law-enforcement list of high-ranking officials acquainted with Gagiyev is incomplete.

With colleagues at Novaya Gazeta, I was able to expand it considerably, adding, for example, the head of one of the most important departments of the Investigative Committee; the deputy minister of industry; a member of the presidential administration; and an officer of a top-secret subdivision of the Interior Ministry.

That’s why Gagiyev’s story isn’t just about one criminal group, or even just one group of corrupt officials. It attests to what Russia’s governing structures have become. Gagiyev was a cog in what must be called government by organized crime.

Extradition or Death

I met with Gagiyev several more times in Vienna. Over the course of these meetings we agreed that I would write about him if he was either killed or extradited (which, to him, amounted to the same thing). Now one of the conditions has been met. Still, for many reasons, I can’t yet describe everything we discussed.

In the first place, we agreed our conversation was off-the-record. Secondly, even if I wanted to tell these stories, I might never be able to prove them.

Several times, interested parties told me that Gagiyev would never get the opportunity to defend himself in a courtroom. They say too many high-ranking people — those who went to him for protection, for money, or for career help— want to solve the problem of Gagiyev in a more informal way that he would understand well.

But whatever happens to Gagiyev in Russia, it’s important for as much of his story as possible to be told.

In investigating his claims, I relied only on information that could be verified through open sources or from criminal case files of other members of the Family, as well as from Gagiyev’s own testimony to the Austrian court that decided on his extradition, which has been posted in the public domain.

It’s probably worth starting with Gagiyev’s biography — as he tells it.

Chapter 2

In which Gagiyev saves his family from Georgian nationalists, frees the hostages in Beslan, is tortured by the FSB, and creates the Family of Brothers.

Photo by Svetlana Vidanova, Novaya Gazeta.

Photo by Svetlana Vidanova, Novaya Gazeta.

Escape from Georgia

“My family lived in Georgia. Then a nationalist came to power, [President Zviad] Gamsakhurdia. I am an Ossetian, we were a minority in Georgia. Ossetians were persecuted. I was still a student and wanted to take my family away,” Gagiyev told the Austrian court.

The judge had a hard time understanding him and asked many times which countries he was talking about — the Soviet Union, Russia, Georgia, or the breakaway republic of South Ossetia. In the late 80s and early 90s, the situation in the Soviet Union was changing so quickly that even its residents didn’t always know which country they were waking up in every morning.

Gagiyev is an Ossetian, an ethnic group derived from the ancient Scythians and Alans who speak a language related to Pashto and Farsi. When the Soviet Union dissolved, they were split between North Ossetia, which ended up in the new Russian Federation, and South Ossetia, which became part of Georgia.

The Ossetians have had a fraught relationship with their Georgian neighbors, and when Gamsakhurdia came to power in 1991, armed clashes broke out.

In those days, Gagiyev was studying nuclear physics in Moscow. “I went [back to Georgia]. I gathered about 40 people … All my relatives were with me. My father’s brother was killed in the time of persecution, and it took us two weeks to get to Russia by foot. There was no transport. A two-month-old baby, my sister’s child, died in my arms on the road. We came to the territory of the Russian Federation — this was North Ossetia — and we settled there in an abandoned house,” Gagiyev continued.

But Gagiyev found no peace in his new home.

In 2004, Islamic militants seeking the independence of Chechnya seized a school in the North Ossetian town of Beslan. The terrorist act resulted in the deaths of at least 333 people, including 186 children, when both special forces and armed locals stormed the school in an attempt to rescue the hostages.It also became a turning point in Gagiyev’s life.

The Beslan Tragedy

Gagiyev says he was one of those who was stormed the school.

“How could we [Ossetians] have allowed Beslan to happen? I haven’t respected myself since then. How did we allow them to sign a repair contract with the terrorists? How did we not see that, day and night, under the guise of doing the work, the bearded men were bringing weapons [into the school]?” agonized Gagiyev during our first meeting in Vienna.

In his Austrian extradition case, he recounted the attack: “When we were in the school, I grabbed two children who were completely exhausted. I dropped my machine gun ... I tried to pick up the girl, but couldn’t. There were explosions, people were shooting, and I was trying to pick up the child, but I couldn’t. Then I noticed that the girl was holding on tightly to her dead mother. Her mother was torn to pieces. So I had to practically carry the girl and her dead mother.”

“It was real chaos,” he told the court. “The tragedy in Beslan changed my life. I felt guilty and wanted to be close to my people. I wanted us to become a free nation.”

After the attack, Gagiyev became famous among his fellow Ossetians. According to him, he had earned his popularity in part by asking uncomfortable questions of the authorities concerning material assistance to the relatives of the deceased. And that’s when, according to his testimony, he ran into a serious conflict with the authorities.

Abduction and Torture

About a month after the terrorist attack in Beslan, Gagiyev was detained.

He explained to the Austrian judge why he thought the authorities had turned on him: “In the media there were reports that a lot of donations had been made to the republic. People from all over the world donated — about 600 million euros. ... So I wondered, where is the donated money? Why can’t the people use this money to bury their children?”

“Then the people of the republic gathered, and we went to the president [of North Ossetia] and demanded his resignation, and the resignation of the head of the special services.”

Afterwards, as he was driving to his parents’ house in Beslan, Gagiyev’s car was stopped by masked men on the road. “It was the FSB (Russian intelligence service),” he said. The men shot into the air, pulled him out of the car, bundled him into their jeep, and drove him to the local FSB department.

“To make me wake up, they pissed on me,” he told the court. “I was stained with blood, and they made a chessboard out of my chest. … These people thought that I was pretending to be unconscious, and they pissed on my wounds, saying: ‘You will be our Jesus Christ.’ And this is the most harmless thing they did to me. They tore apart all my internal organs. I needed several operations.”

Five days later, he was taken half-dead to the border with Kabardino-Balkaria and thrown out of the car wearing only a gown. Heavily injured, he arranged for a trip to Israel, where he underwent surgery and psychological rehabilitation.

Gagiyev’s testimony about being tortured was verified by Austrian experts. “The expert conclusion of Prof. Reiter confirms that the accused was … not only tortured, but treated in an inhumane and degrading manner,” the Austrian court materials said.

The Creation of “The Family”

It was around this time, according to the Investigative Committee, that Gagiyev formed the Family. The group is now no more. Most of its members have been detained at various points, were interrogated, and have given confessions (though many later retracted them, citing torture). But as a whole, the Brothers’ testimonies yield a consistent story of how their organization worked.

Each member of the family was a Brother, and Gagiyev was called the Big Brother or the Elder Brother. Within the group there were subgroups (“brigades,” as the investigation calls them), each with its own leader.

The Brothers were allocated money to buy clothes and cars, to rent apartments, to get medical treatment, for education, and for many other purposes. At their disposal was an almost unlimited arsenal of weapons, including those used only by the special forces. These weapons were mostly acquired in South Ossetia.

During interrogations, the Brothers said that leaving the Family, as well as any actions directed against the Brothers or against the interests of the Family, were punishable by death.

Gagiyev’s co-founder was Sergei Beglaryan (also known as “the Armenian”). Beglaryan and Gagiyev were long-time friends who had studied at university together. According to interrogations files, Beglaryan led one of the most active “working” groups of the Family. In their slang, “working” meant killing.

“No one took any oaths about entering the Family or about any kind of eternal devotion. At one point [Gagiyev] and … Beglaryan declared everyone to be Family and Brothers. Later, whenever anyone entered the Family, they would shake his hand and declare him a Brother,” recalled Goneri Dzhioev, a long-standing member.

Most members of the Family were Ossetians. They entered the group voluntarily and were convinced that they were acting on behalf of their homeland. “Gagiyev is an influential person in Moscow, he is concerned with the well-being of North Ossetia and wants to restore order, to cleanse it of bad people, and for that he needs true patriots,” said one member of the Family in testimony that was echoed by many others. They understood that sometimes these people would need to be killed — but this, in their view, was simply justice.

I saw several of the Brothers speaking in court, and they continue to hold to their views, believing that they had acted correctly. And indeed, many of the Family’s victims were people who were murderers and kidnappers themselves.

But it wasn’t only such people that were killed. Innocent bystanders also fell victim; others were killed over money. And among the Brothers were not only patriots of Ossetia, but also numerous law enforcement officers who had very different motivations.

Chapter 3

In which special service officers join the Family, as well as an undercover police officer who thought nothing of gunning down women, children, and a nun on a weekend trip to a monastery.

A “Fighter” Against Organized Crime

Yevgeniy Yashkin fought in Chechnya, where he received the Order of Courage. He came to the Family soon after it formed in 2004, at the age of 36. At that time, Yashkin was with the Interior Ministry’s Office for Combating Organized Crime in the South-Western District of Moscow.

When Yashkin first met Gagiyev, he knew him under one of his pseudonyms, a businessman named “Valeriy Nikolaevich” (Gagiyev had several passports under various names). Gagiyev offered him a side job: For 30-40 thousand rubles (about US$ 1,100 to 1400) per month, he would work as his personal bodyguard and also help transport goods and documents. In fact, Yashkin was mainly used as a driver, because his official identification allowed him to transport anything without fear of being inspected by his law enforcement colleagues.

Yashkin himself admitted that he had, in fact, given tacit consent to joining the Family when he took part in his first crime — the abduction and subsequent murder of Dmitry Plytnik, a businessman who owned a bank called Natsionalny Kapital (National Capital).

Yashkin told investigators that he first learned of the impending crime during his first year with the Family. He was sitting in a car in Moscow with Gagiyev and a friend who was asking the Family’s leader for a chilling favor: to punish someone who had betrayed him. The betrayer was Plytnik, and Gagiyev agreed to help.

Plytnik was kidnapped near his home. Brothers dressed as law enforcement officers abducted him, handcuffed him, and brought him to the F-1 Ultra M café on Moscow’s Lodochnaya Street — the Brothers’ main base in the city.

Yashkin didn’t see Plytnik being killed. But when he arrived at the cafe, the banker’s body was already in a Ford minibus that was parked in the yard. According to the materials of the case against Yashkin, he was told to “get behind the wheel of this car, because he had an official police officer’s ID, and if they were stopped he could use it to ensure they could drive on without any problems. [Then he was ordered to] take the corpse and dump it into a body of water.”

That’s what they did. Plytnik’s body was thrown into the Volga river near the city of Dubna in the Moscow region. After this first crime, Yashkin played a role in 24 more murders.

Special Forces from the Ministry of Internal Affairs

After Yashkin became a member of the Family, he joined the special rapid reaction unit of the Ministry of the Interior in the Moscow Region. In 2005 he introduced two of his colleagues there to Gagiyev, who also became members of the Family and soon took part in a mass killing.

In 2006, along with other Brothers, they captured four people in a house in the Moscow Region. “Gagiyev said that some scumbags and bastards were ‘pressuring’ some person, threatening him and his family, extorting money. And Gagiyev said that these scumbags should be ‘kidnapped,’” one of the new recruits later said to investigators.

Disguised as policemen — though many needed no disguise, since they really were — the Brothers came to the house of the man who had been asking for help. There they waited for the arrival of the “bastards” and abducted them.

All four were handcuffed, put in a car, and driven away. The Brothers took them to the side of the road, led them into a ravine, put them on their knees, and shot them. Then the bodies were doused with gasoline and burned.

At the time, Yashin was sitting in a car near the ravine and saw the killings. The man who methodically and cold-bloodedly shot each victim in the head was Maxim Nikolayev, who went by the nickname “Pioneer” (or the “Young One”).

Nikolayev was also a law enforcement officer. He served in what is perhaps the interior ministry’s most secret subdivision — the Operative Search Bureau of the Interior Ministry in the city of Moscow. The main task of this department is to surveil foreigners, for which its officers are often known within law enforcement circles as toptuny (“foot-stompers”).

The Killer Foot-Stomper

Even according to his fellow Brothers, Maxim Nikolayev was one of the cruelest killers within the Family. He was subordinate to Family co-founder and working group leader Sergei Beglaryan.

It was Nikolayev, along with Beglaryan, who shot the family of Alexander Slesarev in 2005, in one of the bloodiest and most excessive murders committed by the Family.

Yashkin told investigators that Slesarev and his family were targeted in a murder-for-hire scheme: “[Slesarev], who was to be killed, is the owner of two large Russian banks. One of them is Sodbusinessbank; [I don’t] remember the second one. The man who ordered the killing had his own interest in these banks. [Slesarev] had intentionally bankrupted these banks and withdrew assets worth several billion rubles.”

Slesarev was indeed involved in a high-profile scandal, accused of stealing his depositors’ money. A year before his killing, Russia’s Central Bank had revoked Sodbusinessbank’s license in connection with numerous violations of the law, including laundering the proceeds of crime.

On October 15, 2005, Elizaveta Slesareva, the banker’s fifteen-year-old daughter, returned to Moscow. She had been studying in the United Kingdom and had come home on vacation to see her parents.

On the next day, early in the morning, the family set out in two cars to visit a monastery in the city of Stary Oskol, near the Ukrainian border more than 600 kilometers south of Moscow. Alexander, Elizaveta, his wife Natalia, and their young niece, Sophia, were in the front car. They were followed in a second car by Sophia’s father (Slesarev’s brother-in-law), a driver, and a nun from Russia’s most revered monastery, the Trinity Lavra of St. Sergius.

Someone from the Family who worked in law enforcement had tapped the banker’s phone, so his route was known. As the Slesarev family headed toward the monastery, they were already being followed.

The Brothers first caught up with the rear car, and Nikolayev started to shoot at it while still driving. The car braked sharply. Slesarev’s brother-in-law was hit in the back of the head, but survived. The nun wasn’t so lucky: She was shot right through the forehead. She died afterwards.

Then the Brothers caught up with the front car and blocked its path. Nikolayev and Beglaryan got out of the car and started shooting at the Slesarev family’s Mercedes from 10 meters away. The banker, his wife, and 15-year-old Elizaveta were killed. The niece, Sophia, was shot in the chest, but survived.

Nikolayev was just 23 years old when he committed the massacre. But he wasn’t so unique within the Family. His colleagues, the “foot-stompers” from the same top-secret Interior Ministry department, also took part in many high-profile murders on behalf of other criminal groups. For example, members of the department surveilled Paul Khlebnikov, the former editor-in-chief of the Russian Forbes, in 2004. In 2006, they tracked Anna Politkovskaya, a columnist for Novaya Gazeta. They gave all the information they gathered to hitmen from Chechnya who later killed the journalists.

Chapter 4

In which the Family cleanses North Ossetia of child kidnappers and the head and hands of the murder victim are packed up by the man who oversees the Family’s business ties.

Photo by Svetlana Vidanova, Novaya Gazeta.

Photo by Svetlana Vidanova, Novaya Gazeta.

The Appearance of Barastyr

In the mid-2000s, kidnapping for ransom became an epidemic in North Ossetia. For several years, law enforcement effectively did nothing. But after several final episodes in 2006-2007, the crimes suddenly stopped.

First, in November 2006, the 20-year-old son of an Ossetian entrepreneur, Ludwig Zaseyev, was kidnapped.

“The young man was kept in a pit at a private household ... [the kidnappers] demanded $5 million from his relatives for his release. During the negotiations, the amount was reduced to $700,000. After this sum was paid ... the victim was released two months later,” read a press release from the Investigative Committee.

Then, in August 2007, a Moscow businessman, Chermen Mirikov, was kidnapped and held for a year by people who demanded a $10 million ransom from his family.

“I went to sleep and woke up with only one thought — please don’t let me get my husband’s severed ear or finger in the mail,” his wife told the newspaper Kommersant. “After all, this had happened before. My husband’s brother, for whom we had paid a ransom in Chechnya, is missing the index finger on his right hand. So we started to collect money right away.”

But the deal fell through. According to media reports, the intermediary between the kidnappers and Mirikov’s wife took the money and disappeared. Mirikov was killed.

According to the Investigative Committee, the man who organized the kidnapping was a man named Artur Bekmurzov, nicknamed Kipa.

Kipa’s brother, Kazbek Bekmurzov, was a police official in North Ossetia, holding at various points the positions of the republic’s deputy minister of internal affairs and chief of police — which might explain why the police did little about the kidnappings.

Colonel Bekmurzov refused to believe his brother was behind the crimes. “My brother was no angel ... but I’m sure he had nothing to do with the kidnappings of his fellow countrymen,” he told Kommersant in 2013.

Someone else thought otherwise.

“[After Mirikov’s killing],the kidnappings stopped abruptly. And those who were suspected of these crimes started to die one after the other, or simply to disappear. People talked about how some Robin Hood was at work catching these kidnappers. Some even called him ‘Barastyr,’” said a former interior ministry operative familiar with the kidnappings but not allowed to discuss them on the record.

In Ossetian mythology, Barastyr, the ruler of the underworld, judges people and decides whether they go to heaven or hell.

Who was North Ossetia’s Barastyr?

A Ransom for the ‘Child’

Enter Oleg Gagiyev, nicknamed ‘Bote,’ which means the ‘Child’ in Ossetian.

Bote, who had no relation to Aslan “Big Brother” Gagiyev, was the Brother behind the Family’s pursuit of Kipa’s kidnapping gang and other North Ossetian ‘scumbags.’ According to the Investigative Committee, it was a team run by Bote who shot Vitaly Karayev, the mayor of Vladikavkaz, and Kazbek Pagiyev, the former vice premier of the North Ossetian government.

Bote worked as a counterintelligence operative for the unrecognized republic of South Ossetia. But the members of his team within the Family were sure that they were really working for the FSB.

In an interview with the TV show Chestniy Detektiv (“Honest Detective”), Inal Ostayev, the sniper who killed Karayev for Bote’s group, explained: “These people [that we kill] are a problem for Ossetia. They do various bad things. That’s what I was told, that’s their words, I didn’t invent them. I don’t know what they did … Kidnapped children, robbed someone… I was told that [they should be killed] in Moscow, that the FSB needs this.”

It’s notable that law enforcement agencies long knew about Bote’s group. He and his people faced triple murder charges as far back as 2007, but were found innocent by a jury.

As it turns out, Big Brother may have been behind their “innocence.”

Robert Bagayev, a Brother nicknamed “Robson,” told investigators that he remembered first meeting Bote in November 2007 near the Crocus-Citi Mall on Moscow’s Ring Road — and learning that Big Brother had just paid about $20 million to get him out of jail.

Then, Bagayev said, he drove Bote to the Lodochnaya street cafe, where Big Brother introduced him to the Family as their new Brother.

Shortly afterwards, Bagayev witnessed a conversation between the two Gagiyevs that would lead to the fall of Kipa’s kidnapping gang.

According to Bagayev, Bote explained to Big Brother that three men named Kipa, Lasha, and Gudzha wanted to kill him. Bote knew these people — they had once stolen cars together in Moscow. Since then, with Kipa in charge, the three had formed the North Ossetian kidnapping gang. Bote insisted that they be killed right away, but Big Brother wanted to talk to them first. In the end, the Brothers did both.

A cafe used as a base by the “Family,” with images of famous mobsters displayed on its walls. Photo by Svetlana Vidanova, Novaya Gazeta.

A cafe used as a base by the “Family,” with images of famous mobsters displayed on its walls. Photo by Svetlana Vidanova, Novaya Gazeta.

Kipa’s Kidnapping

“At the end of 2007, Aslan Gagiyev gave an order to kidnap a man named Kipa," said Yashkin, the police officer and driver who had helped dispose of the banker’s body. He described the Brothers putting on black uniforms and masks, taking fake Kalashnikov assault rifles, getting into a Chrysler minivan, and driving to a house in Moscow near the Akademicheskaya metro station, where Kipa lived.

At about 9 a.m., Kipa left the house and got into his Audi A-8, but the Brothers blocked his car, dragged him out, and drove him to what they called their “distant base” near Sheremetyevo Airport.

“This base belonged to Sergei Safronov, also a member of the Family and a businessman. On the first floor of the building there was some kind of workshop and a sauna,” another brother said.

Meanwhile, Kipa’s Audi was taken to a car service Safronov controlled near the Brothers’ cafe on Lodochnaya street, where it was chopped into pieces and scattered in different dumps.

Kipa was taken to Safronov’s office, where both Gagiyevs — Bote and Big Brother — spoke with him.

Bagayev was at the base too, and described the scene to investigators.

“After a while, [Bote] and Maxim Nikolayev took Kipa downstairs, holding him by the arms, and brought him into the sauna. Then Nikolayev put a dark plastic bag over [his] head and, together with Beglaryan, wrapped the packet with tape from his neck to his eyes. Kipa died of asphyxiation. It seems that at this time, Sergei Safronov was nearby, serving scotch,” he said.

Bagayev then went upstairs to talk to Gagiyev about other issues, but then Bote appeared. “Don’t you want to take part in the dismemberment?,” he asked.

Bagayev refused, and Big Brother supported him, saying that he shouldn’t be forced to participate if he didn’t want to. But Bote insisted: “At least look.”

Bagayev agreed. He and Bote went down to the sauna, where Kipa’s headless corpse was lying on the floor. “Standing by the body was Beglaryan, holding an axe in his hands. I realized that it was him who was dismembering [Kipa’s] body. At that moment I saw Safronov packing his head and hands into plastic buckets,” he told investigators.

Four Letters on a Severed Hand

Now the body needed to be disposed of. One Brother who helped in this gruesome task was more reluctant than most.

Ruslan Yurtov came to the family in 2007, at the age of 25. He had been looking for work and turned to his acquaintance Nikolayev, who suggested that he visit the Lodochnaya street cafe. That’s where he first met Big Brother.

“Gagiyev started asking about me, whether I had an apartment, whether I had debts, if I served in the army. He asked if I know how to shoot, to which I answered, I can — I did serve.” Yurtov said.

Gagiyev said that he would arrange for the younger man to get a job with the police, stressing that he should “serve honestly, not take bribes, and make a career — and that he would help.”

That year, Yurtov started working for the police in the Lomonosovsky region of Moscow’s South-Western District, initially as a trainee, then as an operative within the criminal department.

Nikolayev took care of getting him into the service, negotiating with the right people. “Getting a job was done through some kind of police general,” Yurtov said.

Soon enough, the time came for him to do his part for the Family.

In early December 2007, Nikolayev asked him to come to the “distant base.”

Yurtov arrived, went into the sauna — and saw Kipa’s headless corpse in the shower. One of the Brothers ordered him to help dispose of it.

The situation unnerved the new Brother.

According to his testimony, Yurtov reasoned as follows: If he refused, they would kill him too, and then his corpse would be lying next to this one. On the other hand, this unknown man was already dead. He could do as he was told, save his own life, and then try to somehow distance himself from the Brothers.

Yurtov and others tied metal beams to the corpse and loaded it into a minibus. Behind the wheel was Yashkin, with whom Yurtov was closest among the Brothers because both had fought in Chechnya. They took the torso to just outside Moscow and threw it into a hole in the ice. Nikolayev later dumped the other body parts separately in the Tver region north of Moscow.

But they didn’t stay hidden forever. Three years later, an amateur underwater diver found several white buckets in a canal off the Volga river. He brought one to shore, opened it, and found two severed hands inside. Police later found a tattoo reading “GSVG” on one of the fingers, which they eventually deciphered as an abbreviation for Gruppa Sovietskih Voisk v Germanii (a group of Soviet troops in Germany).

The tattoo, among other clues, helped the authorities identify the body as Kipa’s.

A warehouse near Moscow’s Sheremetyevo Airport used as a base by the “Family.” Photo by Svetlana Vidanova, Novaya Gazeta.

A warehouse near Moscow’s Sheremetyevo Airport used as a base by the “Family.” Photo by Svetlana Vidanova, Novaya Gazeta.

Lasha’s Kidnapping

The Family’s pursuit of the kidnapping gang continued.

After police trainee Yurtov had committed his first crime — removing Kipa’s corpse — he tried to avoid the Brothers, citing his work. But Nikolayev, who had brought him into the Family, wasn’t having it. He told Yurtov not to concern himself with his wife or child — just his work for the Brothers — and warned him that he would never leave the Family alive. Beglaryan told Yurtov that if he kept avoiding “family affairs,” they would break his leg with a bat.

In January 2008, Yurtov got another assignment. He was to stand outside a car wash on Moscow’s Garden Ring and watch for a car with certain plates. When it drove in, he called Nikolayev.

A Chrysler belonging to the Family drove up right after, and Brothers dressed in police uniforms and balaklavas, carrying dummy Kalashnikov rifles, jumped out. They went inside, shouting “Everybody lie face down, hands behind your head! Police!”

They were looking for Lasha Avlokhashvili, Kipa’s kidnapping associate. And they found him. The Brothers grabbed Avlokhashvili along with a friend, nicknamed the Georgian, who was simply in the wrong place at the wrong time. Both were taken first to the office of the Financial Leasing Company on Makarenko Street in Moscow — a state business where Gagiyev worked and that played an important role in the Family’s financing.

“With Lasha, they were interested in the circumstances of the kidnapping of Ludwig Zaseyev’s son. [Lasha] first denied everything, but after [Bote] beat him on the chest and back with a billiard ball in a hat, and Nikolayev poured boiling water on his back, [Lasha] divulged the circumstances of the kidnapping, even how the money was divided,” Bagayev told investigators.

After Lasha confessed, he and the Georgian were taken to the base by the airport. Zaseyev was brought there as well. “[Big Brother] called Ludwig Zaseyev and said: ‘Here’s the person who kidnapped your child,’ pointing to [Lasha]. Then [Big Brother] suggested that Zaseyev kill Lasha himself, but Zaseyev refused. So [Big Brother] ordered Nikolayev to do it. Nikolayev put a plastic bag on Lasha’s head and, together with Beglaryan, wound his head with tape,” recalled Bagayev.

Just as with Kipa, by the time Yurtov arrived, he had missed the killing. Lasha was already dead. “The other man, the Georgian, was still alive. He was saying to leave him alone, he was sick with AIDS, he wouldn’t live long anyway, and wouldn’t tell anyone anything,” Yurtov recalled during interrogation. But Bote ordered the Georgian killed as well.

“One of the guys went to the store and brought a few axes, knives, sets of work clothes, rubber gloves and shoes, plastic wrap … Then they all changed and started to dismember the corpses ... Nikolayev and Beglaryan cut them apart, the others helped hold onto the body parts and bag them.”

“To make the chopping more convenient, they put something wooden — boards or timber — under the bodies. They cut the head off first, then the hands, then the arms up to the elbows, then to the shoulder, then their feet, then the leg to the knee, then to the pelvis. The body itself was not cut into pieces. Safronov kept worrying that the walls would get stained with blood.”

“This was all done at night. Before dismembering the corpses, they took off all [the victim’s] clothes, and took all their documents out. Safronov would get rid of these things, burning them in the sauna in the firebox or somewhere else on the base. The heads and hands were put in buckets, Safronov poured in some kind of mortar,” Yurtov described everything in detail.

Safronov was an important Brother who many of the others testified about.

Even as he strangled victims and disposed of their severed heads and hands by night, by day he directed a network of companies that kept the Family well financed — by stealing money from the state budget.

Chapter 5

In which Big Brother explains how he paid millions of euros to high-level officials and in which it’s revealed that he was owed big favors for sitting a prison term for a member of the presidential administration.

The Keeper of the Family’s Assets

Sergei Safronov was born in Miropol, a small town in Ukraine’s Zhytomyr region. In the 1990s he lived in St. Petersburg. It’s unclear when and how he joined the Family, but it’s clear that he played a very important economic role: Many of the assets the Brothers used were registered in his name.

For example, Safronov owned 50 percent of Tex-Master TM3, the car service on Lodochnaya street in Moscow where the cars of the Family’s victims were chopped up. He also co-owned the F-1 Ultra M café, the Brothers’ base on the same street, where Brothers could eat for free. It was also where they gathered to plan their murders.

Safronov was also the sole owner of a warehouse complex called Gruppa Attache, the “distant base” near Sheremetyevo airport. So many people were killed there that no matter how hard the Brothers tried to clean the walls, investigators still found traces of blood during their search.

Safronov’s company ties also lead in another direction.

In the very end of 2006, he co-founded a construction company called Laguna Breeze in Khimki, a city near Moscow. His partner was Irina Zhukova, the common-law wife of Anatoly Korotkov, once the head of one of the Investigative Committee’s most important departments. At least in Gagiyev’s words, Korotkov was a deputy to the agency’s head, Alexander Bastrykin – a major player both in Russian politics and in corruption.

(When questioned by reporters, Zhukova said she remembered the name Laguna Breeze, but that she didn’t know anyone named Safronov. She said she had no recollection of what this company did and didn’t know why she was listed as one of its founders.)

What connected Korotkov, who died in 2015 as a senior official responsible for stopping corruption in Russia, with the Family?

“Bastrykin’s Deputy”

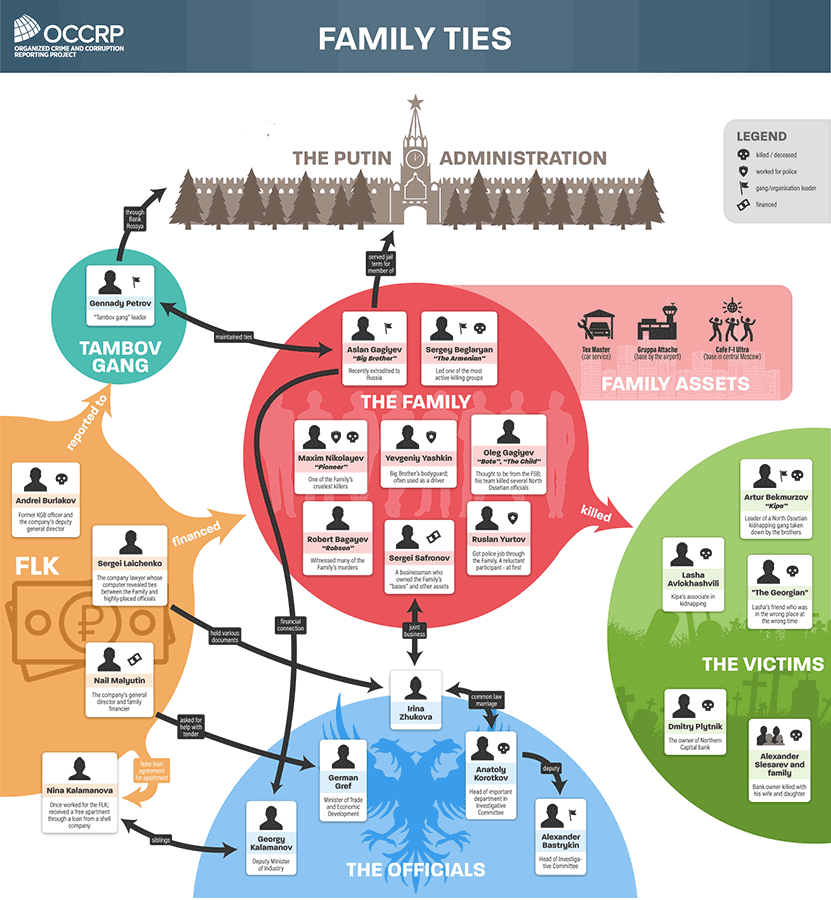

Diagram of "The Family's" connections to Russian government officials and other influential figures. Click to enlarge. Credit: Edin Pasovic / OCCRP In Austria, Gagiyev told the court how crime and business operates in Russia: He said he was paying off the country’s chief anti-corruption official.

Diagram of "The Family's" connections to Russian government officials and other influential figures. Click to enlarge. Credit: Edin Pasovic / OCCRP In Austria, Gagiyev told the court how crime and business operates in Russia: He said he was paying off the country’s chief anti-corruption official.

“All business in Russia is built in such a way that it’s impossible to do business without giving money to those who are in power. There are certain amounts for each level of business. I paid 1.2 million euros every month from my association to Bastrykin at the Investigative Committee,” Gagiyev explained to the Austrian judge.

By “my association,” Gagiyev meant the Financial Leasing Company (FLK), a state company that was supposed to develop Russia’s commercial aircraft industry. The company would buy airplanes from Russian aircraft factories and then lease them to airlines, which often didn’t have the money to buy the expensive planes themselves. To this end, the government kept allocating it billions of rubles from the budget.

Gagiyev held no official position with the FLK. But, judging by testimony from many of the company’s employees, everyone — including the directors — answered to him. Ordinary workers knew Gagiyev as Valeriy Nikolaevich. “There was a feeling that he was some kind of very important person. We decided that he was from the FSB: He looked sternly at everyone,” explained the chief accountant.

Gagiyev told the Austrian court that, at some point, the money he was paying to the Investigative Committee stopped reaching its main recipient, and that’s why the Russian authorities finally went after him.

“There was an unexpected meeting with a deputy of this Bastrykin — a director of one of the departments,” Gagiyev told the court, referring to Korotkov. “Everything was fine. I gave him money because I had a business. Then he asked me how my business was going, and I said ‘better than before.’ From that point on, I started to have problems… Either my partner didn’t give the money to Bastrykin or [Korotkov] didn’t pass the money to Bastrykin.”

Gagiyev’s testimony about passing money to highly placed Russian officials could be considered an attempt to politicize his extradition fight, except for a few points. First, Safronov’s joint business with Korotkov’s wife is a clear tie between Investigative Committee officials and the Family.

Furthermore, a set of documents found in the computer of Sergei Laichenko, the FLK’s legal advisor, show a further connection.

Investigators found these while looking into the company’s later collapse. Among them was a power of attorney in Laichenko’s name signed by the same Irina Zhukova, Korotkov’s wife. The computer also contained documents pertaining to her property in Moscow and the Black Sea town of Anapa. Laichenko also had powers of attorney from people who were selling property to Zhukova.

Gagiyev’s claims to have been bribing top Investigative Committee officials would explain why Laichenko, the FLK lawyer, would be carrying out deals for the wife of the director of one of the Investigative Committee’s most important departments.

Irina Zhukova told reporters that she didn’t recognize the name FLK, but that she did recall the name of its general director, Nail Malyutin. Zhukova admitted that she had granted power of attorney for the sale of an apartment in Moscow and the purchase of a house in Anapa to Laifchenko. But when asked who put her in touch with him, she said that she didn’t remember.

“Imagine that you got sick, and you come to your friend and ask him if he knows a good doctor. And he recommends his good friend. This is the same situation. Somebody recommended me a good and trustworthy lawyer. And I gave him a power of attorney,” she said.

She also confirmed that Korotkov had been her partner, and defended him. “By the age of 60, a man could have hundreds of contacts. Theoretically I don’t exclude that [Korotkov] could have been acquainted with somebody from [the FLK]. Lots of people revolve around big officials. And [as one of the leaders of the Investigative Committee], he talked to many people. When you meet somebody, you can’t predict whether this person will become a fraudster or killer,” she said.

But the findings relating to Zhukova weren’t the only ones that should have surprised operatives searching the home of a seemingly ordinary lawyer.

Deputy Ministers and Others

Among the files in Laichenko’s computer was a loan agreement from 2008 for 28.3 million rubles (about $1 million) between a company called Greenwood and Nina Kalamanova, who had worked at FLK from 2005 to 2009, first as a deputy director of the legal department, then as an advisor to the general director. This is a very large loan for someone in her position.

She is also the sister of Georgy Kalamanov, today Russia’s Deputy Minister of Industry and Trade (who, at the time, was director of one of the ministry’s departments).

With the loan she received, Kalamanova acquired an apartment in the elite “Solnechny Bereg” community on Moscow’s affluent Michurin Prospect.

Greenwood, which had issued the loan, had all the signs of a ghost company used for this one deal. It made no insurance payments to the Pension fund, and when an attempt was made to hold it accountable in 2009, the court simply couldn’t find any traces of it: “The organization at the indicated address did not exist.” In 2010, the tax authorities removed the company from the register of Russia’s legal entities as non-existent.

Kalamanova wasn’t in debt for long. Documents found on Laichenko’s computer show that she paid off the entire 28.3 million rubles just two months later, in cash and with interest. What was also suspicious is that according to the metadata on the files, all these documents had been created on Laichenko’s computer. Moreover, they all — the loan agreement, the receipt for depositing the cash repayment, and the document confirming that the loan was repaid — were edited on one day: May 12, 2008. This implies that the paperwork had been created to explain the money used to buy the new apartment.

All of this seems to show the FLK giving the minister, or at least his sister, a free apartment in one of Moscow’s most expensive neighborhoods.

Georgy Kalamanov didn’t reply on the request for comments.

The deals make sense if you believe Gagiyev’s testimony in Austria, where said that he had also made payments in return for a good relationship with the Ministry of Industry.

“I paid another €1.2 million to the Minister. We belonged to the Ministry of Industry. So [in total] I had to pay €2.4 million every month [to both the Investigative Committee and the Ministry of Industry]. Not only me, but my partners, with whom I worked together, had to pay. But I was responsible for the finances, to get the money to the right people,” Gagiyev said.

So how did “Russia’s No. 1 Killer” make such connections?

The Tambov and the Presidential Ties

Gagiyev had further ties to two very important people who, at first glance, appear to come from different worlds. In fact, they don’t.

One is a criminal like himself who long ago fled Russia to sunnier Spain, where he was later arrested, but fled after posting bail. The other is a shadow — an unknown, but presumably highly placed, member of Russia’s presidential administration.

A document from one of the criminal cases against the Brothers says: “According to available information, in the ‘90s, A.M. Gagiyev served a prison term for an economic crime, having taken the blame for one of the currently active employees of the presidential administration of the Russian Federation (complete personal data are unknown). This ‘debt’ did not remain unpaid, and now this ‘acquaintance’ plays an important role in the life of A.M. Gagiyev, who thanks to this acquired a number of connections with highly placed officials in the Russian Federation’s government bodies.”

The identity of this member of the presidential administration is unknown.

This same document states that Gagiyev maintained relations with leaders of the Tambov organized crime group in Spain.

Which of these connections is more valuable in modern Russia is an open question, since it’s not always clear where the Tambov group ends and the presidential administration begins.

For many years, Tambov leaders had a stake in Bank Rossiya from St. Petersburg. According to the U.S. Treasury, their fellow shareholders include members of Putin’s inner circle. (Click here for an earlier OCCRP report on Bank Rossiya, the jewel of Putin’s financial empire.)

FLK itself also seems to sit in two different worlds — the state and organized crime. Its board of directors included officials from the president’s administration and the government. They were supposed to monitor how state funds were being spent. But at the same time, FLK staff appeared to report to Gagiyev on a daily basis. And not just him. According to Spanish police, the FLK’s directors regularly reported to Gennady Petrov, a Tambov gang leader.

For many years, Spanish police monitored Petrov’s phone and the phones of those around him, to find that he is, in fact, one of Russia’s most influential people. He easily made arrangements to meet with the former Defense Minister, Anatoly Serdyukov; closely communicated with Duma member Vladislav Reznik; received information from the deputy director of the Federal Drug Control Service, Nikolai Aulov; paid medical expenses to Igor Sobolevsky, Alexander Bastrykin’s former deputy in the Investigative Committee; and had a business in common with the former deputy director of Presidential Affairs Department Ivan Malyushin, and many others.

The FLK’s general director, Nail Malyutin, was also a Petrov contact and reported to him about every decision, as if Petrov, and not the government, was the company’s main shareholder. “You’re the helmsman of the convoy, and we’re just here to hand you the shells. I wipe them down, and the others hand them to you,” Malyutin said to Petrov in a conversation intercepted by Spanish police.

Malyutin and “distant base” operator Safronov are key links in the FLK affair.

In testimony to investigators, Malyutin remembered that he met Gagiyev in 2001 through Safronov, who he knew from his St. Petersburg days.

After Putin became president, his cronies came to Moscow to take up key roles in the government. A mass invasion of the “Petersburg crew” began.

Malyutin tried his luck in the capital, too, where he could capitalize on his friendly relationship with German Gref, with whom he had worked in the 1990s in the Committee for Management of State Property of St. Petersburg. In the 2000s, Gref became Russia’s Minister of Trade and Economic Development.

“The St. Petersburg ties functioned in Moscow,” Malyutin explained to investigators. Once in the capital, he called Safronov, who invited him to play football. In the sports hall, according to Malyutin, he met Gagiyev and Andrei Burlakov, a former employee of the KGB’s foreign intelligence service, and at the time, the FLK’s deputy general director.

As Malyutin recalled, Burlakov invited him to work at the FLK, but set a condition — to help the company win a government tender to lease commercial aircraft. “Using Gref’s position, I asked him to use his influence to move FLK’s bids forward. Understanding the importance of the moment and being grateful to Gref for his very kind and selfless attitude towards me, I gave my personal guarantee that if it won the tender, FLK would fulfill its requirements in the best possible form,” Malyutin said, explaining his request to Gref.

According to Malyutin, the FLK ended up with the tender, and he was named the company’s deputy general director.

Gref didn’t reply to a request for comment.

In Malyutin’s words, he met Gagiyev again in the state company’s offices. But this time, for some reason Burlakov introduced Gagiyev as “Valeriy Nikolaevich.” Seeing Malyutin’s surprise, he explained: Gagiyev is “from the secret services, and this is the way it has to be.”

Malyutin worked at the company until 2004, then returned in 2007 to be its director, allegedly at Gagiyev’s request.

In that role, he was able to fulfill many of the Family’s needs. “Malyutin was providing for all the guys I knew, the guys in the Family. When [a Brother] was caught, Malyutin called and gave large sums of money, which were used to rent houses for the guys [who were being sought by police],” one of the Brothers, Dmitry Kodoev, said in court.

Chapter 6

In which the Family falls apart and the Brothers start killing each other, a killer writes a confessional letter, and Big Brother praises Austria.

Lots of Money — Lots of Blood

Around 2008 or 2009, as FLK employees recalled, conflicts broke apart the company’s leadership, and several decision-making centers formed. Everyone was trying to carve out a slice of the pie for themselves. Amidst the fighting, billions of rubles that the government had allocated to the company to develop the commercial aircraft industry simply evaporated.

A criminal case about the disappeared funds was opened in Russia and soon led to financial disputes among both the company’s formal and informal heads.

First, in March 2011, the Brothers kidnapped Malyutin, the FLK’s director. He was brought to a house near Moscow to speak with Gagiyev. As members of the Family recalled in their testimonies, Gagiyev reproached him for “stealing money from the company.”

Malyutin later told investigators that Gagiyev beat him and accused him of firing his people, even as the FLK was spiraling toward bankruptcy. Then Gagiyev allegedly said that he “wouldn’t be able to explain to his people if he [Malyuytin] left here alive.” Eventually, however, he let Malyutin go.

A few days later, a frightened Malyutin flew to Austria, but he was arrested and extradited back to Russia. In May 2018, he was sentenced to six years in prison for a separate episode of embezzlement from the FLK.

One could say that Malyutin got lucky. Another FLK manager did not.

Gagiyev had been looking for Malyutin’s deputy, Andrei Burlakov, for a long time. In his eyes, Burlakov, too, had stolen money from the FLK, disappeared, and refused to get in touch, Brother Georgiy Dzugutov would later tell investigators.

At the end of June 2011, Dzugutov and another member of the Family were driving near the Krasnopresnensky embankment in Moscow when they spotted a dark blue Bentley – the exact kind of car Burlakov owned. They followed it to a restaurant called Khutorok, and sure enough, Burlakov got out.

The brothers followed him for the next few months and found that he frequently came to the restaurant. On Sept. 29, 2011, Yashkin brought his fellow Brother, Yurtov, to the restaurant.

Yurtov, who had once tried been reluctant even to dispose of a dead body for the Brothers, went inside, confirmed that Burlakov was there, ordered some tea, and went to the bathroom. He put on gloves, pulled out a gun, and, coming up to Burlakov’s table, shot him and his common law wife Anna Etkina at close range.

Burlakov died at the scene, although Etkina survived.

The next year, in 2012 , the FLK was declared bankrupt. Most of the withdrawn funds were never returned.

One of the companies that never repaid the FLK was Safronov’s Gruppa Attache, which had received 24 million rubles (about $760,000) from the state company. Safronov withdrew the money and never returned. When police later visited the abandoned base, nothing but traces of blood from dismembered corpses remained.

The End of the Family

The end of the Family came about dramatically.

Robert Bagayev was put on a wanted list in 2009 because one of the Brothers had testified that he had been an accomplice to a murder. Bagayev went into a family safe house to avoid getting caught.

“Within the Family, the practice was for those who were wanted by police to live in one of the houses the Family rented specifically for this purpose. The wanted person lived a quiet life and did not appear in public places. All his needs were taken care of by the Family. While the wanted people lived at this dacha, the Family prepared documents for them with changed personal data so they could leave the country,” Bagayev explained to investigators.

As he remembered, around 2010, he and other Brothers who were hiding from the law were taken to a dacha near Moscow. Gagiyev came and explained that “the Family’s state of affairs were bad: Beglaryan and Nikolayev have lost their minds, they want to kill [Gagiyev] and all of them, so we need to find them first and kill them ourselves.”

Yurtov found Nikolayev and convinced him to talk to Gagiyev. Witnesses said that Nikolayev, the Family’s most prolific murderer, and Gagiyev talked all night. Gagiyev asked Nikolayev why he wanted to leave the Family and kill the Brothers. Nikolayev answered that Family co-founder Beglaryan had convinced him.

Everything seemed to end well: The longtime Brothers embraced. Gagiyev invited Nikolayev to come to the dacha, where the wanted him to ask the other Brothers for their forgiveness. Nikolayev seemed to agree.

But as soon as they left the base, Nikolayev took off running and yelling: “Help, police!” Nikolayev, who had ushered so many victims to their deaths himself, realized he would be next. But he couldn’t escape.

Nikolayev was brought to the dacha. Both he and Yurtov, who was part of his crew and therefore no longer trusted, were tied up with tape and left in a workout room. Gagiyev gathered all the Brothers who were in the house and interrogated his fellow Brother in their presence.

“[Nikolayev] admitted that he had been reporting information about the Family to the police, where he continued to work, as well as to their enemies,” Bagayev said, recalling the conversation, which lasted into the evening. Then, in his words, everyone went upstairs and Gagiyev asked every Brother what they thought should be done. Almost all voted to kill Nikolayev.

The Brothers went back down to the workout room. They killed Nikolayev in the same way that he had killed so many others — with a plastic bag over his head, wrapped it in tape. A bound Yurtov watched Nikolayev die.

“After Nikolayev confessed that he had planning to kill some Brothers, immediately suspicions arose about Yurtov, who had brought Nikolayev into the Family and who was heavily influenced by Beglaryan,” Bagayev recalled. But Gagiyev spoke with Yurtov and decided not to kill him, he said.

On the next day, Yurtov helped dismember his former Brother. The corpse was thrown into the forest by the side of the road, and the severed body parts burned. But two months later, in February 2011, the Brothers realized that the snow was melting and that the body could be discovered. They went to look for it, found it, and buried it more securely.

The body with no head, arms, or legs would not stay buried. It was uncovered a second time by a top-secret police unit in August 2015. It was in the woods, on the 11th kilometer of the Moscow-St. Petersburg highway, 70 meters from the road.

Next the Brothers started hunting for Beglaryan. Two attempts were made to kill the Armenian. First, he was lured to a meeting at the Lodochnaya street cafe, but the guns of both assassins failed. Beglaryan miraculously escaped the ambush.

Two years later, in 2012, they finally discovered the house where’d been hiding. The Brothers waited for him at night and shot him down in his car with a massive hail of gunfire.

Other Brothers started to fall as well.

Also in 2012, Bote, the South Ossetian counterintelligence agent, was found guilty of committing seven murders and sentenced to life in prison.

Yevgeniy Yashkin, the former interior ministry operative, was released last year by the Moscow City Court: After all of these killings he had a nervous breakdown and also developed schizophrenia. The court sent Yashkin to compulsory treatment.

His friend, the once-reluctant murderer Yurtov, is awaiting trial. From the detention center he sent a letter to Anastasia Burlakova, the daughter of the FLK director he had killed, begging for forgiveness.

“I’m very sorry and I repent what I did, that I brought grief to you and your family. I can’t forgive myself for this and have no right. I will suffer and live with this my whole life!,” he wrote.

Gagiyev fled Russia for Austria.

Big Brother Makes His Last Appeal

In his closing speech to the Austrian court in 2015, Gagiyev asked once again not to be extradited.

“I don’t have any chance of surviving. I’ve seen a lot in my life. I’m not afraid of death; since 2004 I haven’t felt like a living person, I have only a shell left, nothing more. I don’t have a single organ that isn’t damaged. So I ask you to understand me,” he pleaded.

In the end Gagiyev spoke about what Austria offered that Russia didn’t.

“I’m grateful to the whole Austrian community for the fact that my children are getting a good education and aren’t afraid to go out on the street. Since I’ve been in this country, I haven’t seen any stray dogs or cats, and this says a lot about a society’s culture. And I would like my people to live just like the Austrians do.”

He ultimately got the justice he wanted least: To be sent back to Russia, run by the cronies who once were his friends.