Italian food safety inspectors made a disturbing discovery late last month: Horse meat imported into the country from Belgium was laced with dangerous levels of cadmium, a heavy metal that is toxic to humans.

The European Union has a mechanism for alerting its member countries about such public safety risks. It quickly sprang into action, issuing an alert that pointed to Romania as the origin of the contaminated meat.

This isn’t the first time such an alert has been issued. Nor is it the first time that Chevideco, a Belgian company, has imported and resold bad horse meat from Romania. On four previous occasions, all in 2014, meat handled by the company was found to have unacceptably high cadmium levels.

The precise Romanian origins of the latest alert are not yet known. But in each of the previous four cases, Chevideco had imported its meat from a pair of affiliated Romanian companies.

This investigation is based on six months of reporting by two partners of the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project (OCCRP) — the RISE Project in Romania and the Investigative Reporting Project Italy (IRPI) — as well as Knack, a weekly Belgian newsmagazine. Using leaked inspection records and hundreds of documents obtained under Freedom of Information laws, reporters looked into how and why contaminated horse meat is still being sold in Europe.

As a new investigation reveals, these companies — Agromexim and Cetina — have on multiple occasions made use of counterfeit documents. The falsifications, which appear to have been carried out by veterinarians and Romanian officials responsible for food safety, raise questions about the meat the two firms continue to export across the European Union.

Olivier Kemseke, Chevideco’s director, says the company has continued to buy Romanian horse meat because he considers his supplier reliable, and previous problems with cadmium were quickly handled. “And we had additional tests done in Romania. Testing, testing, testing,” he says. “I think the horse today is the most tested animal in the world.”

Both Cetina and Agromexim denied responsibility for the falsifications, noting that the documents were issued by veterinarians.

One Year, Four Cadmium Alerts

Horse meat scandals are nothing new in the EU. Perhaps the biggest and best-known occurred in 2013 when Dutch meat trader Jan Fasen was at the heart of a scam in which Romanian horse meat was sold throughout Europe labeled as 100 percent beef.

But 2014 was a particularly bad year. The first negative headlines appeared in August, when Romanian inspectors found illegal levels of cadmium in the kidney meat of a horse slaughtered in the north of the country.

A map showing the path of contaminated meat that was detected by the European Union’s rapid alert system in September 2014. Click to enlarge. (Sergiu Brega, RISE Moldova)Romanian horses may be ingesting the cadmium when they eat contaminated grass. A 2015 study by researchers at Romania’s Babes-Bolyai University found that “the soil in the Baia Mare mining area is contaminated especially with lead, copper, zinc and cadmium” due to pollution and improper storage of mining waste.

A map showing the path of contaminated meat that was detected by the European Union’s rapid alert system in September 2014. Click to enlarge. (Sergiu Brega, RISE Moldova)Romanian horses may be ingesting the cadmium when they eat contaminated grass. A 2015 study by researchers at Romania’s Babes-Bolyai University found that “the soil in the Baia Mare mining area is contaminated especially with lead, copper, zinc and cadmium” due to pollution and improper storage of mining waste.

Whatever the reason for its contamination, the contaminated meat was sold across Europe. Some was subsequently recalled; some had already been consumed.

More bad news came in September, when Italian inspectors also found cadmium contamination in Romanian meat.

In both cases, the meat came from animals sourced by Agromexim, slaughtered by Cetina, and imported to Belgium by Chevideco.

It then fanned out to the shelves of large Belgian retailers like Cora and Intermarche, and was also exported to the Netherlands, Switzerland, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, and Italy.

The European Rapid Alert System for Food and Feed (RASFF noted that in France, for example, some of the meat had been sold to consumers before the alert reached officials.

In Belgium, Chevideco “strongly advised” buyers “not to consume this meat anymore, but to return it to the point of purchase where they will be reimbursed.”

The results of the recall varied in the other countries (see map).

According to Romanian law, producers that repeatedly sell meat containing illegal residues must be monitored by the authorities for at least six months, during which time they are banned from selling products or carcasses until they are cleared by lab tests.

Horse #968000002524306

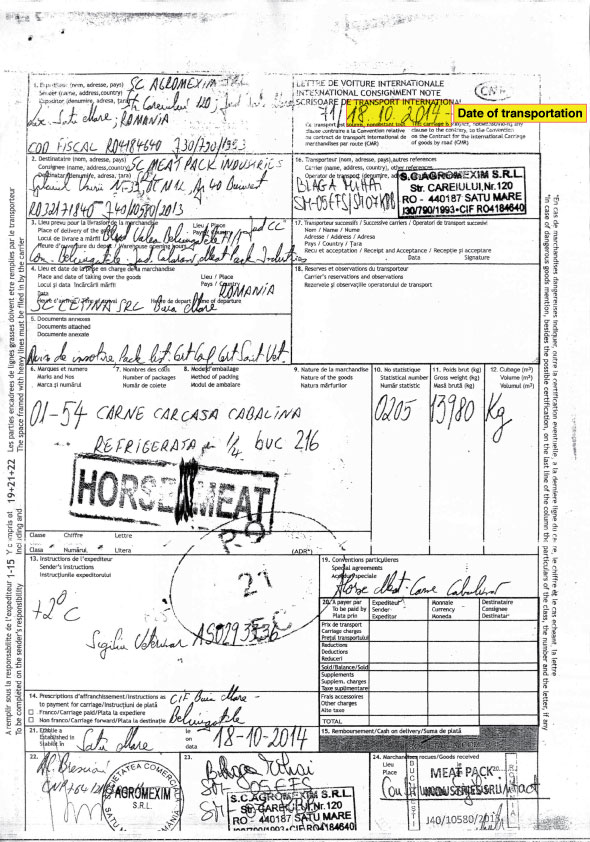

This female horse lived in Bistrita Nasaud County in north-central Romania — a region polluted by mining — until her owner sold her to Agromexim in 2014. She was slaughtered by its partner company, Cetina, also in that year, along with 53 other horses. She became part of lot #425, which weighed a total of 14,000 kilos. A government veterinarian signed a certificate confirming that the meat and organs had come from healthy animals.

Transportation documents show that lot #425 left the slaughterhouse on Oct. 18, 2014.

But according to laboratory records, the tests on the meat were only performed three days later, on Oct. 21. The results did not become available until Nov. 11, and they were not good: There was 65 percent more cadmium in the mare’s muscle tissue than is allowed by law.

By this point, the horse meat had been transported to Belgium. Some then traveled to France, where it ended up on dinner plates.

(Cetina disputes the dates in this analysis, claiming that the samples had been taken on Oct. 18 and arrived at the laboratory on Oct. 21. This is contradicted by the company’s own documents.)

Nevertheless, a third alert — again involving the two Romanian companies and the Belgian Chevideco — was issued in November.

A look at the history of the specific animal that triggered the recall shows how the meat slipped through the cracks: Though a sample had been sent to a Romanian lab for analysis, the meat was exported before the results were finalized (see box).

A fourth alert took place in December, triggered by Italy, where inspectors flagged Romanian horse meat with nearly twice the legal limit of cadmium: 0.36 milligrams per kilo, (up to 0.2 is allowed). Once again, the meat ended up in various European countries: Belgium, France, and the Netherlands.

Once again, inspectors notified the RASFF and initiated a recall.

The European Commission’s Directorate-General for Health and Food Safety confirmed that investigations are ongoing in different countries but couldn’t provide any more documentation.

“Their disclosure would undermine the purpose of ongoing investigations in the involved members of the RASFF (Italy, Belgium, the Netherlands, Romania, France, Estonia, Finland, Hungary, and Switzerland,” the directorate-general said.

Cetina’s Falsified Documents

A set of documents accompanying lot #425 which show that this horse was certified as ready to export even though the lab results — which showed unacceptable levels of cadmium — would not be ready until the following month.In all four alerts, the meat had been shipped by Meat Pack Industries, a Romanian sister company to Chevideco (the two are owned by the same Belgian umbrella company).

A set of documents accompanying lot #425 which show that this horse was certified as ready to export even though the lab results — which showed unacceptable levels of cadmium — would not be ready until the following month.In all four alerts, the meat had been shipped by Meat Pack Industries, a Romanian sister company to Chevideco (the two are owned by the same Belgian umbrella company).

This company has its own suppliers — two firms based in northern Romania called Agromexim and Cetina.

The horses are sourced and sold by Agromexim. But they are slaughtered by Cetina, which also plays another crucial role: Since Agromexim doesn’t have the authorization it needs to export meat from Romania, Cetina certifies the meat, which is then shipped by Meat Pack.

Cetina is a family-run company with 270 employees and a turnover of €11.3 million last year. It owns a slaughterhouse and a meat-processing plant that delivers more than 10 tons of cold cuts to about 50 Romanian supermarkets per day.

The company has been struggling financially for years, and owes money to the state budget.

It has also run into serious trouble — beyond selling cadmium-laced meat.

Romanian regulations require companies that sell horse meat to maintain careful records that contain information about the identity and health of the horses.

Cetina’s slaughterhouse in northern Romania. (Photo: RISE Project)

Cetina’s slaughterhouse in northern Romania. (Photo: RISE Project)

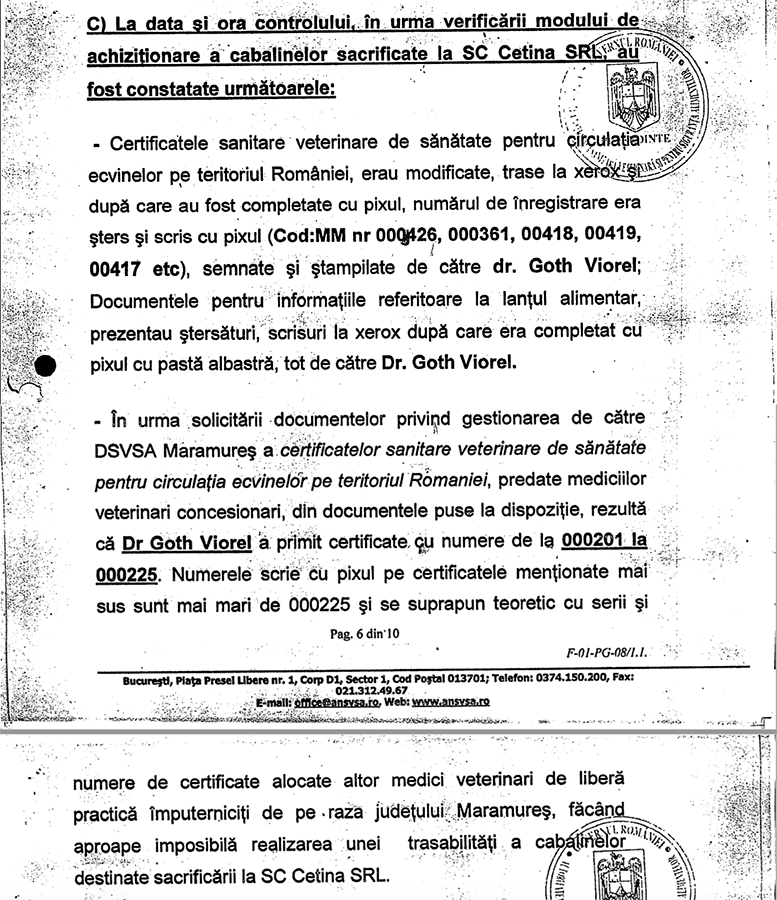

But in 2014, while investigating cadmium contamination at Cetina, Romanian inspectors discovered that several types of documents — including sanitary veterinary certificates and food chain papers — had been falsified. The counterfeit documents had often been photocopied and filled out by hand.

According to a report issued by investigators, some of the counterfeit documents had been issued by Goth Viorel, a veterinarian from Maramures County.

The section of the investigators’ report discussing counterfeit certificates issued by Dr. Viorel.Viorel had allegedly been allotted certificates with serial numbers starting with the series 000201 through 000225. Yet the numbers on certificates found in Cetina’s slaughterhouse were written by hand and had serial numbers from a later series, some of which overlapped with certificates assigned by other veterinarians.

The section of the investigators’ report discussing counterfeit certificates issued by Dr. Viorel.Viorel had allegedly been allotted certificates with serial numbers starting with the series 000201 through 000225. Yet the numbers on certificates found in Cetina’s slaughterhouse were written by hand and had serial numbers from a later series, some of which overlapped with certificates assigned by other veterinarians.

Reporters were not able to reach Viorel for comment.

In November 2014, in connection with both the falsified documents and the cadmium contamination, ANSVSA, Romania’s food safety authority, suspended Cetina’s license to slaughter horses (though the facility was allowed to continue killing other animals).

The slaughterhouse was allowed to resume operations in late August 2015. The decision was made by Viorel Vasile Pop, the deputy director of DSVSA Maramures, the local ANSVSA office.

Pop told RISE reporters that the agency had acted properly in allowing the slaughterhouse to resume its operations.

“We, the sanitary directorate, did our job by the book,” he says. “After our people did an inspection, the slaughterhouse was reopened. All the deficiencies had been addressed.”

He cut the conversation short when asked about the allegedly faked documents.

In a separate case, Pop is under investigation by anti-organized crime prosecutors, who suspect him of leading a criminal group that specializes in tax evasion, money laundering, forgery, fraud, and abuse of office. Investigators say the group registered fake animals to obtain agriculture subsidies and that veterinarians registered those animals with Pop’s help.

Meanwhile, Cetina’s troubles weren’t over. The inspectors would be back — prompted by a separate investigation that reached all the way across Europe.

Operation Gazel

In April last year, Fasen, the Dutch meat trader who had been accused of selling horse meat as beef, was arrested in Belgium for allegedly leading what Europol, the EU’s police agency, later described as an ”organized crime group” that sold meat “unfit for human consumption” across the continent.

Another 65 people were arrested in Spain, and simultaneous operations were also carried out by local police in France, Portugal, Italy, Switzerland, and the United Kingdom. All were coordinated by Europol in an operation it called “Gazel.”

Those arrested were charged with crimes against public health, document forgery, money laundering, and animal abuse.

Romania was involved too.

“We can confirm that Romania was a part of the horse meat Operation Gazel,” Tine Hollevoet, a Europol spokesperson, told Knack reporters in an email. “I can also confirm that Gazel is still ongoing. Several follow-up investigations have been initiated.”

Neither Europol nor the Romanian police would say which companies in Romania might be under investigation in connection with this probe.

Chevideco and its Romanian partners, Cetina and Agromexim, all deny any connection to Fasen.

But the Europol operation did bring investigators back to Cetina’s Romanian slaughterhouse.

At the European agency’s request, ANSVA inspectors returned in May 2017 to look into 30 shipments of horse meat, 373 tons in all, that it had made to an Italian company called Fratelli Sibilia between 2014 and 2016.

Most were found to have problems — again involving counterfeit documents.

Duelling Reports

For unknown reasons, ANSVSA sent two teams of inspectors to Cetina on the same day. The first filed a harshly critical report, but the second found virtually nothing wrong. Both reports were filed under the same number.

ANSVSA said only that “the reports contain the inspectors’ conclusions based on the documents they checked at Agromexim and Cetina.”

The second, shorter report found one mistake in a passport number and designated it a human error. It checked 43 horses and managed to identify the origins of 41 of them — a good result.

But in the first report, inspectors said they found sanitary-veterinary certificates with the serial numbers filled in by hand, after the original printed numbers had been erased. In other cases, medical records were incomplete, showing no information about diseases the animals may have suffered or treatments they’d received.

The first report also notes another issue.

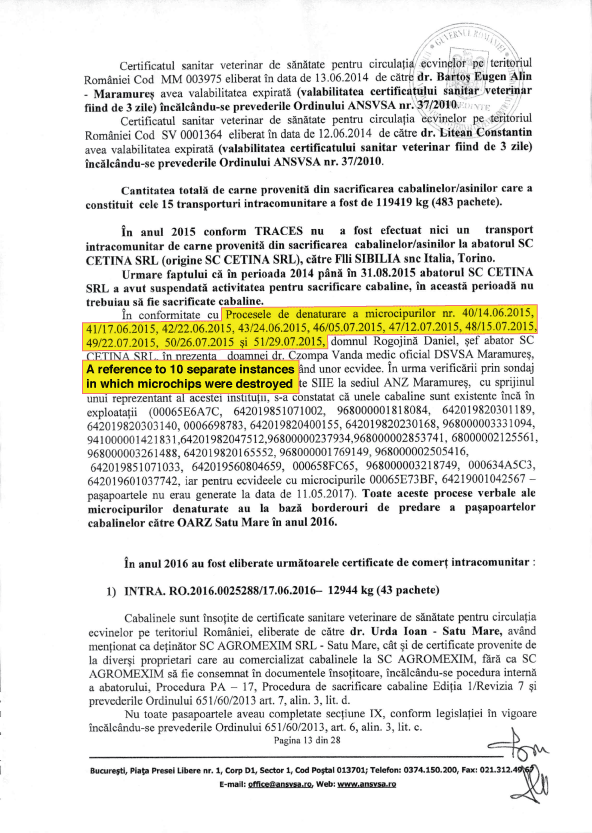

Though Cetina had been banned from slaughtering horses between November 2014 and August 2015 as a result of its earlier problems, the report found that “between June and July 2015, horses may have been slaughtered, despite the fact that it is forbidden by the suspension order.”

In Romania, all livestock raised for food must be microchipped and issued a passport to record innoculations and medical history. When an animal is killed, its microchip is to be removed and destroyed, and the slaughterhouse must sign documents along with the government veterinarian indicating how many chips have been destroyed.

Officials at Cetina apparently continued documenting microchip destruction during the suspension period.

In response to reporters’ questions, Cetina claimed that “it was one error in writing the document that attests the destruction, [a] situation that was clarified with the sanitary veterinary authorities.”

An excerpt from the investigators’ report, showing 10 separate instances in which microchips were destroyed.In fact, the investigators’ report contains a reference to 10 instances in which microchips were destroyed. It is unclear how many illegally killed horses this could represent.

An excerpt from the investigators’ report, showing 10 separate instances in which microchips were destroyed.In fact, the investigators’ report contains a reference to 10 instances in which microchips were destroyed. It is unclear how many illegally killed horses this could represent.

As for the other problematic documents, Cetina denied responsibility.

“None of [the required documents] are being issued by Cetina. After slaughtering, the passports are sent to the eminent authority, which never reported irregularities related to [these] documents, and never indicated fake passports.”

“Sometimes, [the] documents [contain] writing errors and are not complete, but in some situations, the documents have been corrected after[wards] by the same veterinarian.”

Indeed, some of the fake documents found in 2017 had been issued by local veterinarians.

ANSVSA, which oversees DSVSA Maramures, noted in its reports that the lower-level agency had failed to notice discrepancies and recommended disciplinary action.

Reporters asked Pop, the agency’s deputy director, about the newly revealed issues.

“I don’t know,” he says. “The measures have been taken accordingly. I don’t know more, I only deal with the animals’ health. More I cannot say, except the fact that inspections have been made.”

Pop ended the conversation before reporters could ask about the destroyed microchips.

Another portion of the counterfeit documents found by inspectors had accompanied the live horses that were being supplied to Cetina by Agromexim. These had been issued by local veterinarians throughout northern Romania.

In response to reporters’ questions, the company’s founder and director, Alessandro Bresciani, says that the new allegations are not his problem.

“Agromexim is a simple trader,” he says. “Meat compliance is established by the official veterinarian that was assigned to the slaughterhouse. I paid for this service.”

Agromexim had €5 million in revenue last year, selling almost 10,000 horses between 2016 and 2017. Most of the meat was exported directly to Poland, Italy, Germany; another portion is sent to Belgium via Meat Pack.

Bresciani says that he and his company are not to blame for the spread of contaminated meat throughout Europe. He says that he doesn’t know Fasen, the Dutch trader, except from the internet.

He suggests several possible explanations for the cadmium contamination.

“Pollution. Exhaust emissions,” he says. “Maybe the knife that cut the meat in Italy, the packaging, the truck that transported [it], or the hand that smoked a cigar before touching the meat.”

Agromexim has kept its customers despite the scandals. Reporters talked to one of its regular buyers, the Italian company Fratelli Sibilia.

Managers there defended their supplier. “The horses aren’t reared in a closed environment like other species,” wrote Paolo Sibilia, an owner, in an email. “This involves environmental pollution (Chernobyl, emissions into the atmosphere of various types, etc). Herbivores can absorb some of this pollution, especially through grass and water, if it is contaminated.”

Sibilia has continued to work with Agromexim. According to Bresciani, the most recent shipment was delivered on June 23.

After the ANSVSA’s 2017 report, Romanian police asked the local prosecutors’ office from Maramures County to open a criminal case for abuse of office and forgery. The case was redirected to the prosecutor’s office from Baia Mare city, and is ongoing.

A Chevideco facility in Belgium. The company has imported and resold cadmium-laced horse meat from Romania. (Photo: Kristof Clerix / Knack)

A Chevideco facility in Belgium. The company has imported and resold cadmium-laced horse meat from Romania. (Photo: Kristof Clerix / Knack)

More Bad Meat

Last year, the Agromexim-Cetina partnership generated a new European alert for cadmium- contaminated meat — its fifth one.

The meat was sold to the Italian company Boventi SPA, which sent it on to Germany and Hungary.

The source of the cadmium contamination has never been identified, according to the Romanian authorities.

Meanwhile, Chevideco, the Belgian buyer, continues to buy horse meat from Agromexim.

A tour of his clean and orderly facility revealed horse carcasses hung from hooks in refrigerated rooms and spotless delivery trucks.

Labels on boxes packed with horse steaks indicated Romania as the origin.

“[Agromexim director Alessandro Bresciani] has been selling us up to 70 horses per week for the past 15 years,” Kemseke says. “We are still working with him today. Of course. He is a correct and loyal supplier and has a good reputation.”

Kemseke says he saw no reason to abandon someone for “running a red light once.”