But according to a new investigation by hetq.am, a partner of the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project (OCCRP), the Moscow lab at the heart of the Russian scandal helped a group of Armenian weightlifters use banned drugs to win Olympic medals in Beijing in 2008 and London in 2012.

Seven members of the national weightlifting team, including two medalists, provided details of the doping program to reporters. Three spoke on the record and the others asked to remain anonymous. The head of Armenia’s anti-doping agency, Areg Hovhannisyan, as well as an official from neighboring Georgia, also spoke with reporters and provided additional information about the cooperation with Moscow.

The picture that emerges is of a complex operation that used several different methods to evade international anti-doping testing. These included helping athletes obtain performance-enhancing drugs, warning them ahead of time when urine samples would be taken, storing clean samples to outwit the system, and, above all, performing repeated tests to ensure that only athletes that could submit clean samples faced international scrutiny.

Any test results that came back positive were falsified as clean — with Moscow’s help.

Tigran V. Martirosyan, who was awarded a silver medal for his 2008 performance in Beijing, told hetq.am that Armenian officials made sure team members were clean before sending them to any competition. “They took the samples so they could tell if we were clean or not,” he said. He has never failed a drug test.

Aghasi Aghasyan, a former member of the Armenian national weightlifting team, confirmed that Armenian athletes who might test positive for drugs were screened to protect them from consequences on the world stage. “We’d send our samples before the competitions. If they saw, for example, that my sample was clean, I’d be sent to compete,” he said. “If another weightlifter wasn’t clean, he wouldn’t go.”

“Everything was done so that no one was caught. I can’t say for certain who sent the test samples -- but the [Armenian Weightlifting Federation] was working to see that no one got caught.”

All of the samples were sent to Grigory Rodchenkov, former director of Russia’s anti-doping center in Moscow; though some of the athletes have admitted that they were doping, the lab certified them all as clean.

Pavle Kasradze, the head of the Anti-Doping Agency in neighboring Georgia, says it was well-known that “if one wanted to falsify the results, you’d have to go to Rodchenkov.”

Hovhannisyan, the head of Armenia’s anti-doping agency, confirmed this assertion: “They sent [the samples] to Rodchenkov and paid him in cash.”

Areg Hovhannisyan, head of Armenia’s anti-doping agency. (Photo: Ministry of Sport and Youth Affairs)

Areg Hovhannisyan, head of Armenia’s anti-doping agency. (Photo: Ministry of Sport and Youth Affairs)

The former Russian sports official has since become widely known as a whistle-blower, revealing extensive details of the Russian lab’s operations to the New York Times, the US broadcast news magazine “60 Minutes,” and in the Oscar-winning documentary “Icarus.”

The athletes told hetq.am that the Armenian doping program was no secret in the weightlifting world. They said they either purchased the drugs themselves or that the Armenian Weightlifting Federation (AWF) provided them free of charge.

In the end, the Russian program was exposed — and the Armenian athletes were caught in the aftermath. The scandal continues to cost them dearly.

Two of the team members were stripped of their Olympic medals. Armenia's national team is not competing in the European Senior Weightlifting Championship, which began yesterday in Romania.

And along with eight other countries — Russia, Kazakhstan, Belarus, Azerbaijan, China, Ukraine, Moldova, and Turkey — Armenia was slapped with a one-year suspension from all international weightlifting competition. According to Armenian sports officials, that decision was due to be reviewed by the IWF board on March 26, but no conclusions have yet been published.

To Win at Any Cost

Officials and athletes agree that Armenia’s doping program dates from Samvel Khachatryan’s tenure as president of the AWF from 2006 to 2012 and that it grew out of the country’s intense desire to win Olympic medals in 2008 and 2012.

“The doping began at the time of Samvel Khachatryan,” said one athlete who insisted on anonymity. “They didn't force you to use, but you had no choice. If you didn’t use, someone else would. And he or she would take your place on the team.”

Khachatryan left the team after the 2012 games. Reached by phone, he refused to comment. “I don’t want you to question me,” he said, and hung up.

The sanctioned Armenian weightlifters took anabolic steroids as performance enhancers. Data later collected by the International Olympic Committee (IOC) shows that the most commonly-used were Stanozolol and Turinabol.

These substances help athletes get stronger faster than those who train drug-free. They can be detected in urine for months, which is why the World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA) has instituted increasingly rigorous testing across all sports. The athletes are usually tested in their home countries, but only a few labs are certified to manage testing results. The entire program is overseen by international officials.

And this was the program Armenian officials helped their weightlifting team to subvert. It began with helping some of the weightlifters gain access to steroids.

“They would get performance enhancers at a low price from Ukraine and sell them here,” declared another athlete on condition of anonymity. “They weren’t sold to the national team, but given free. The drugs weren’t expensive; 100 [pills] for 20,000 dram ($42).”

“In my case, I didn’t have the money to buy vitamins. But I had 1,000 dram ($2) to buy the enhancers. [The drug] was cheap and sold in drugstores. I was a kid. I bought and used it,” says former team member Aghasyan.

Next, a number of ruses were used to avoid detection.

One involved warning athletes in advance that tests were coming.

In 2009, WADA certified Armenia’s own anti-doping agency, known as ARMNADO, to administer drug testing within the country. (Armenia does not have its own testing laboratories; it is not known where ARMNADO sent its samples for tests in its first two years of operation.)

The international rules were clear: According to WADA rules, ARMNADO was to conduct testing without giving prior notice to officials, coaches, or athletes.

But Hovhannisyan, who has headed ARMNADO since 2009, says that the weightlifting federation would contact the agency in advance by official mail, requesting tests and specifying exactly who should be tested.

The Armenian athletes say they were told on what date they should stop using to allow enough time for the drugs to clear their bodies so they could test drug-free. Nobody flunked a test administered in Armenia.

Hripsime Khurshudyan, a bronze medalist at the London Olympics in 2012, told the Armenian news agency Mediamax: “We didn’t use any drug, even vitamins, without the permission of the doctors. But if they tell the athlete that the body can clean itself [of any substance] in 10 days, we believe it.”

Hripsime Khurshudyan returns home from the 2012 Olympic Games in London. (Photo: PHOTOLURE / Hayk Badalyan)

Hripsime Khurshudyan returns home from the 2012 Olympic Games in London. (Photo: PHOTOLURE / Hayk Badalyan)

Still other techniques were used when international doping officers came calling.

In some cases, athletes were warned in advance. “When official testers from overseas would visit, we’d more or less know which day our urine would have to be clean, so we could pass one test. This continued until the [2012] London Olympics,” one athlete said on condition of anonymity.

The athlete also said that, in other cases, the visitors were given refrigerated drug-free urine samples.

Hovhannisyan at ARMNADO confirms this technique. “The doping testers would call in advance. The athletes would hand over old samples. This was a well-known practice.”

To Russia With Love

Starting in 2011 and until 2014, all samples were sent to the WADA-accredited Moscow lab run by Rodchenkov. Several sources told hetq.am that other post-Soviet countries also used the lab.

This was where, according to Pavle Kasradze, head of Georgia’s anti-doping agency, the results for that came back dirty were falsified in collusion with Armenian officials. “When you talk about cheating mechanisms, don’t exclude [the possibility] that the samples were dirty but the results were clean,” he said.

When athletes tested dirty, they were protected from disqualification by the Moscow falsifications. But they still needed to ensure their subsequent samples were clean in order to make sure they would not be disqualified in separate tests at any upcoming competitions.

The athletes said on the condition of anonymity that, between 2008 and 2012, the AWF warned them they’d end up paying out of their own pocket if they sent in a dirty sample. “They told us that it cost 120 euros to analyze each sample at the Moscow facility, and we’d have to pay if a second test was needed," one athlete said. "If the first sample turned out dirty, a second sample was sent.”

This athlete added that many were tested twice, so they would know how long it would take their own bodies to become clean of the performance-enhancing drugs.

Officials at ARMNADO would send samples from athletes in other sports to different laboratories, including one in Austria, as it does today. But for weightlifters, the samples were always sent to Moscow.

Though the Armenian records are incomplete, and only show collaboration with the Moscow lab for 2013, the fact that the lab was used from 2011-2014 is confirmed by the Annual Operations Report of RUSADA, the Russian Anti-Doping Agency.

Questionable Oversight and Misleading Paper Trails

The Eastern European Regional Anti-Doping Organization (EE RADO) is based in Tbilisi. In theory, the participation of this separate, higher-level body would ensure that the Armenian athletes weren’t cheating. But, in practice, the official listed in the annual reports as representing EE RADO in Armenia, Karen Stepanyan, was an Armenian who also used to collaborate with ARMNADO. Kasradze, the head of both EE RADO and Georgia’s anti-doping organization, describes this a cost-saving measure.

According to WADA’s World Anti-Doping Code, “Anti-Doping Organizations shall, at least annually, publish publicly a general statistical report of their Doping Control activities, with a copy provided to WADA.”

But ARMNADO did not publish reports for 2009, 2010, 2014 and 2015. Its website no longer works. Other countries (including Georgia, Azerbaijan, Ukraine, Kazakhstan and Moldova) have also failed to publish frequent annual reports.

The End of the Affair

The Armenian operation came to an end after the Russians’ own program began to unravel.

In 2015, WADA declared that the Russian Anti-Doping Agency was not in compliance with the World Anti-Doping Code, and Rodchenkov’s lab was suspended.

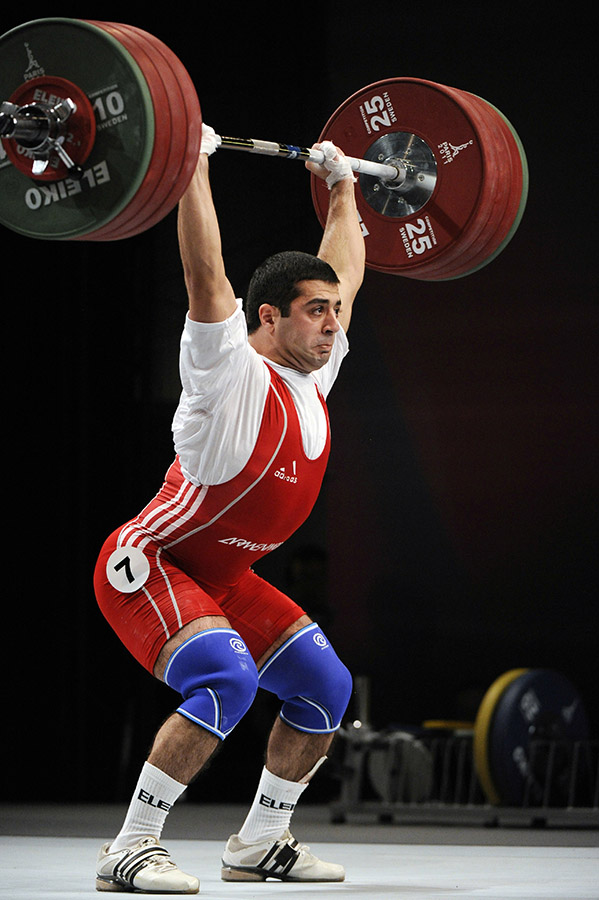

Tigran G. Martirosyan competes during the finals of the 2011 World Weightlifting Championships on November 10, 2011 in Chessy, near Paris. (Photo: AFP PHOTO / BERTRAND GUAY).Further damaging evidence of Russian doping was revealed in the 2016 WADA investigation, also called the “McLaren Report,” which led to Russia being banned from competing under its own flag at this year’s Winter Olympics in South Korea (though lifetime bans for 28 individual Russian athletes were later overturned by the Court of Arbitration for Sport, which decided Rodchenkov’s evidence was insufficient to prove their guilt).

Tigran G. Martirosyan competes during the finals of the 2011 World Weightlifting Championships on November 10, 2011 in Chessy, near Paris. (Photo: AFP PHOTO / BERTRAND GUAY).Further damaging evidence of Russian doping was revealed in the 2016 WADA investigation, also called the “McLaren Report,” which led to Russia being banned from competing under its own flag at this year’s Winter Olympics in South Korea (though lifetime bans for 28 individual Russian athletes were later overturned by the Court of Arbitration for Sport, which decided Rodchenkov’s evidence was insufficient to prove their guilt).

In 2016, the IOC decided to retest samples originally taken during the Summer Olympics in Beijing and London. The focus was on countries that had used the Moscow lab. Athletes whose samples failed the retests faced suspension from competition and, in some cases, revocation of their medals.

This was where the Armenian cheating was caught on an international level.

As a result of the retests, on Oct. 20, 2017, Armenia was one of nine members of the International Weightlifting Federation slapped with a one-year suspension from international competition for illegal drug use. Two Armenian weightlifters were stripped of their Olympic medals, the AWF had to pay a fine of $50,000.

The two who lost their Olympic medals were Tigran G. Martirosyan, who won bronze in Beijing in 2008, and Hripsime Khurshudyan, who won bronze in London in 2012. None of them contested IOC’s decision. (Tigran G. Martirosyan is not related to Tigran V. Martirosyan, who won silver in 2008 and has never tested positive.)

Coach: Everyone Was Doing It

In 2016, when it was announced that Armenian weightlifters had to return their Olympic medals, head coach Pashik Alaverdyan of the men’s national team said at a press conference: “Athletes from everywhere were using those drugs. But 100 or 120 days before doping tests, you had to be clean."

Pashik Alaverdyan, head coach of the men’s Armenian national weightlifting team. (Photo: Armenian National Olympic Committee)

Pashik Alaverdyan, head coach of the men’s Armenian national weightlifting team. (Photo: Armenian National Olympic Committee)

Hetq.am asked Alaverdyan, who has been head coach since 2015 but has served as general secretary of the federation since 2012, how much he knew about the doping program.

“I didn’t send test samples,” he said. “Nor did I know the results. I had nothing to do with it. I can’t answer any questions. I’ve been in charge for three years now, and no one has even had a bloody nose. Please write that I know nothing.”

The athletes who spoke to hetq.am agree that Alaverdyan wasn’t involved in the sale or distribution of performance enhancers.

The two Olympic bronze medal winners who lost their medals, Martirosyan and Khurshudyan, had each been awarded 10 million dram (worth about $20,800 in 2018) by the Armenian government.

In response to a hetq.am inquiry as to whether the award money would be repaid or seized, the Ministry of Sport and Youth Affairs wrote: “The money hasn’t been returned to the government coffers. There are no laws specifying deadlines on return or seizure of the awards.”

Armenia’s Minister of Sport and Youth Affairs, and the ex-Secretary General of National Olympic Committee of Armenia, Hrachya Rostomyan, blame neither the institution he leads nor the athletes for the doping scandal. He claims that the guilt lies with the former management of the weightlifting federation.