Prince Michael of Kent has long enjoyed a measure of celebrity in Russia. Sporting a familial resemblance to his distant relative Nicholas II, Russia’s last tsar, the prince built up a cult following among nostalgic monarchists, who showered him with gifts and flew him around on private jets.

Over the years, Queen Elizabeth II’s cousin has lent his name to everything from Russian educational charities to property developers. His royal credentials allegedly gained him access to President Vladimir Putin’s inner circle — contacts that The Sunday Times reported he offered to sell to the highest bidder.

Prince Michael has previously denied having any special relationship with Putin. But it now emerges that two of his business partners have worked extensively for oligarchs who rank among the Russian president’s closest childhood friends.

The prince and Sergey Markov, a former Soviet diplomat and lawmaker who served as a director in the prince’s charitable foundation and several companies where he held stakes, first got into business in 2005. Later, the prince partnered with another Russian businessman, Maxim Viktorov, who in 2012 was an advisor to the country’s defense minister.

All three took stakes in RemitRadar Ltd., a U.K. tech company that promised huge profits by offering migrant workers insurance deals and links to ways to send money back home. After being appointed the company’s global ambassador, Prince Michael used his name to raise its profile while also privately lobbying Middle Eastern governments and pulling strings at the U.K. foreign office. Despite the royal seal of approval, RemitRadar failed to get off the ground.

A new leak of thousands of emails and documents, obtained by IStories and OCCRP, has revealed how Viktorov and Markov helped blacklisted billionaire Boris Rotenberg, a childhood friend of Putin’s, get around the financial, legal, and reputational problems caused by sanctions. The emails, dubbed the Rotenberg Files, reveal that the two men helped Rotenberg dodge sanctions at the same time Prince Michael was flexing his royal credentials to drum up business for their shared interests. (There is no suggestion that Prince Michael was involved in or knew about any efforts to help Rotenberg dodge sanctions.)

About The Rotenberg Files

The Rotenberg Files is an investigative project based on a leak of over 50,000 records, including nearly 30,000 emails and some 12,000 documents, that shed light on how Russia’s most infamous oligarchs, the Rotenberg brothers, dealt with being sanctioned by the West.

Around the time Prince Michael became RemitRadar’s ambassador, Markov and Viktorov were hiring lawyers to get Rotenberg’s accounts unfrozen. A few months later — as the British royal was representing RemitRadar to Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates — the Russians set up a secret meeting with Rotenberg and the head of a Luxembourg bank in Monaco.

Dame Margaret Hodge, a U.K. MP and chair of the All-Party Parliamentary Group on Anti-Corruption & Responsible Tax, criticized the prince for retaining shares in a company alongside Markov and Viktorov at a time when the U.K. government is discouraging business with Russia following its invasion of Ukraine.

“The idea that [Prince Michael] can act in a way that is contrary to British foreign policy and the U.K. government’s approach is utterly reprehensible,” said Hodge.

“He should be an exemplar of best practice. He has a duty, his status makes him a representative of Britain.”

Responding to OCCRP’s reporting partner, The Times, Markov denied being an associate of Rotenberg, saying he had only met him once, and had never received money from him nor done business with him.

“As an English speaker I helped other people several years ago with some communications related to Mr Rotenberg’s wish to seek legal advice or explore banking relationships in the EU,” Markov said in an email.

Viktorov did not respond directly to questions about his relationship to Prince Michael or investments alongside the prince. But he said neither he nor any of his companies had ever violated any laws, “in particular, the U.S. and EU sanctions legislation.” He described reporters’ findings as “erroneous.”

Boris Rotenberg and his family members did not respond to emailed questions.

After Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine last year, the EU and U.K. joined the United States’ earlier sanctions of Rotenberg, and Prince Michael publicly distanced himself from the Kremlin. But he remains a shareholder in RemitRadar alongside Markov and Viktorov.

Prince Michael declined to comment for this story. Nick Chance, the royal’s private secretary, spoke to reporters in an interview but did not respond to follow-up questions.

Royal Ambassador

Prince Michael burst onto the scene in Russia in 2004, when he made a whirlwind tour of the country as patron of the Russo-British Chamber of Commerce. Breathless media reports from the time described how the prince partied in a Chekovhian mansion and was “showered with gifts,” including a factory in Siberia.

His friend, the Marquess of Reading, reportedly described him as "Her Majesty's unofficial ambassador to Russia.”

That June, the nonprofit Prince Michael of Kent Foundation was set up to support cultural and educational programs in Russia, backed by two companies owned by the billionaires Vladimir Evtushenkov and Dmitry Pumpyansky, who were both sanctioned last year as part of a package of U.K. measures against Russian oligarchs following the invasion of Ukraine.

Two months later, Markov was appointed as the foundation’s director.

By that time, he had already served a long diplomatic career. After graduating from the Ministry of Defence’s Institute of Foreign Relations, Markov held posts in several Latin American countries in the 1980s and early 1990s. In 2012 he was elected to local office in central Moscow as a deputy for the socially conservative “A Just Russia” party, campaigning on an anti-corruption ticket that took direct aim at Putin’s government.

Yet, while Markov was in office, the emails show, he was also acting for Rotenberg, who made billions from state contracts through his ties with the president.

Chance, the private secretary, said Prince Michael was patron of the Russian National Orchestra, then directed by Markov. “They met over a mutual love of music,” he told OCCRP.

Photos on the foundation’s website showed Prince Michael and Markov attending a ceremony to give an eight-ton bell to a monastery in the historic Russian city of Kostroma and meeting dignitaries at Saint Petersburg’s Pushkin House cultural center.

"[The prince’s] name was the main asset of the Prince Michael Foundation,” former senior employee Evgeniy Aksenov told OCCRP. Markov supported the prince when the royal visited Russia and often accompanied him to meetings, he added.

Markov and the prince soon became close business associates. In 2005, public records show Prince Michael set up a property firm called Arts House with Markov as the director.

It’s not clear when they first met, but Markov and Viktorov, a lawyer who did his military service with Russia’s KGB in the early 1990s, crossed paths at the prince’s foundation, where Viktorov was a board member from 2006, and at Arts House. Viktorov’s foundation and company paid as much as $660,000 for a majority of shares in Arts House, business plans, emails, and court papers in the leak suggest.

Prince Michael, Markov, and Viktorov had ambitious plans: Viktorov invested in Arts House just as it was considering building a $150 million, 2,300-seat concert hall and hotel complex in central Moscow, though in the end it was never built due to a lack of funds.

Around the time Arts House developed plans for its concert hall, Prince Michael and Markov became co-shareholders in another Russian investment and property management firm named New International School of Prince Michael of Kent. That project, too, failed to get off the ground.

In 2011, Prince Michael’s consultancy, Cantium Services, invoiced Viktorov’s Legal Intelligence Group for $2,500 of “general consultancy” work. An email chain from 2018, which was forwarded to Viktorov, shows Markov discussing a deal, with Chance in copy, that at one point stood to earn Cantium more than a million British pounds ($1.3 million) in “Structuring and Success Fees” from the sale of a fund. There is no confirmation the deal went through. Chance and Markov did not respond to questions about it.

‘Exceptional Privilege’

The trio are also co-shareholders in RemitRadar, a U.K.-registered tech company. Markov and Prince Michael became shareholders in 2016, acquiring five and one percent of the company respectively — Prince Michael’s private secretary, Chance, also picked up a one percent share. Russia-registered Investment Programs Foundation, run by Viktorov and his family, took another five percent two years later. Viktorov’s company Legal Intelligence Group Limited also acquired shares in 2021.

The company had multiple other shareholders, but Markov became the CEO and ran it.

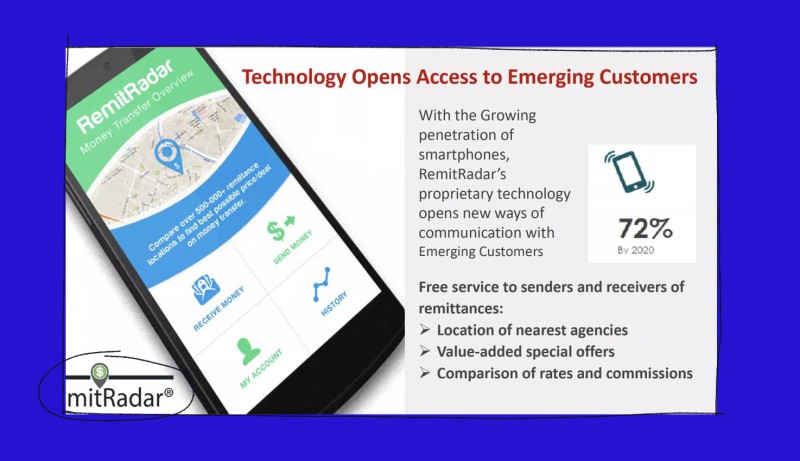

RemitRadar aimed to provide a platform for insurance companies and money transfer organizations to reach billions of new clients, including hundreds of millions of migrant workers. In return for sharing their personal data, these people would get access to better deals on remittances and even free insurance policies.

In a promotional video, the prince portrayed his work for RemitRadar as a push for “migrant workers' financial inclusion,” but he has not publicly discussed his shareholding.

Prince Michael soon set to work using his contacts to promote RemitRadar’s business — both publicly and, the leaked emails show, by using his royal contacts.

In late 2017, his foundation hosted a launch event for RemitRadar in Moscow that featured him and Markov as speakers. According to an internal memo, the Prince Michael of Kent Foundation was even empowered to sign agreements with partners on RemitRadar’s behalf and did so, including with a subsidiary of state-owned Russian bank VTB.

Behind the scenes, Prince Michael was also lobbying Middle Eastern monarchies for RemitRadar. One letter from Saudi Arabia’s ambassador to the U.K. welcomed his overtures and praised “Your Royal Highness’ efforts to better the circumstances of the foreign working communities.”

The leak indicates Prince Michael’s office also contacted the Crown Prince of Abu Dhabi, whose undersecretary said his proposal deserved “further study.” It’s unclear exactly what Prince Michael proposed, but business plans, which appear in the leak, show the United Arab Emirates became a priority market for RemitRadar, with Markov planning to target up to 400,000 migrant laborers a month in the country.

Documents show that the prince’s staff pulled strings in the U.K. to enable Viktorov to join Prince Michael and Markov as a shareholder of RemitRadar. In late 2018, Prince Michael’s private secretary contacted a senior U.K. diplomat in Moscow, asking for Viktorov’s visa application to be expedited so he could attend a board meeting to finalize his investment in the company.

“Anything that you might be able to do … would be enormously appreciated,” wrote Nick Chance in an email to the diplomat on November 26.

Responding the same day, the diplomat said he had “been in touch with the visa team.” Two days later, emails show, Viktorov bought a Moscow-to-London plane ticket.

It was at this board meeting, held at a private club in London’s upscale Mayfair district, that Viktorov bought into RemitRadar, taking a five percent share for 111,000 euros ($126,000) through Investment Programs Foundation, the foundation run by Viktorov.

“It’s completely and utterly inappropriate for any member of the royal family to abuse their position to try and get access or speed up a visa. It’s using his platform and his power to provide a favor for a friend. It offends the very integrity and reputation on which Britain is built and trades,” Hodge, the British M.P., told OCCRP.

RemitRadar said it “undertakes due diligence on all individuals and companies that are associated” with it, and that it “is not aware that any improper pressure or lobbying took place” over Viktorov’s expedited visa.

Chance did not respond to questions about his role in contacting the U.K. diplomat in Moscow.

The U.K.’s Department for Business and Trade said “Where there is a clear national interest – such as to support inward investment – requests for visas can be expedited. The applicant applied using our Priority Visa Service, and his application was processed in the usual timeframe of five working days.”

Reflecting the hype around fintech companies, Goldman Sachs estimated RemitRadar to be worth $200 million in 2018, predicting it would grow to $318 million by 2023. Speaking at a 2018 United Nations conference on migration, Markov said the company offered “an all-round, win-win solution that works for everyone, everywhere.”

But soon after, things fell apart.

In a 2019 memo in the leak titled “Where has it gone wrong?,” Markov detailed how RemitRadar’s relationship with its insurance partner in Russia had broken down after it failed to strike deals with money transfer companies.

Aksenov, who also worked at RemitRadar, told OCCRP the company initially attracted several thousand migrant workers from Central Asia, but it couldn’t secure enough funding to continue. Chance told OCCRP RemitRadar “never got off the ground” after one of its co-founders withdrew, then the COVID-19 pandemic hit.

“The company came to a juddering halt,” he said.

Chance was in the process of selling his share, he said, and Markov and Viktorov are “considering what to do next with the company.”

Mystery Russian Business Partner

After Putin ordered a full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, Prince Michael said he would return a presidential Order of Friendship that he had been gifted in 2009 and resigned as patron of the Russo-British Chamber of Commerce. The Prince Michael of Kent Foundation’s website, once covered in smiling pictures of the prince and his Russian charitable initiatives, was taken offline.

But the British royal hasn’t entirely cut ties with his Russian business partners.

Prince Michael and Markov remain shareholders of RemitRadar. Viktorov’s foundation and U.K.-registered Legal Intelligence Group also still hold shares in the company.

And despite RemitRadar’s apparent failure as a business, it managed to attract another Russian business partner. In 2021, a Russian closed-end investment fund called Consul purchased around 4 percent of RemitRadar.

Consul, which was set up around a year before the investment, is managed by Viktorov’s Russian asset management firm, Evocorp, but its ultimate beneficiary is a mystery: In Russia, organizations like Consul, called ZPIFs, aren’t obliged to enroll with the state register of legal entities or publicly disclose who ultimately owns them.

Leaked minutes from a June 2017 meeting at the Russian Central Bank list 13 ZPIFs managed by Evocorp — all of which were owned by or linked to the Rotenberg brothers.

Markov told OCCRP partner The Times that “neither Boris Rotenberg nor Rotenberg family members hold any stake in RemitRadar directly or indirectly.