At a meeting in May, Tajikistan’s president sternly lectured a room full of bureaucrats about the pitfalls of corruption.

Central Asia’s poorest nation faces regular budgetary shortfalls, he said, because “unscrupulous” officials turn a blind eye to the smuggling of undeclared goods across the border.

“How do we fill the budget? Where are you looking? Hundreds of millions, billions, are bypassing the budget,” President Emomali Rahmon said at the gathering of state employees in the capital city of Dushanbe.

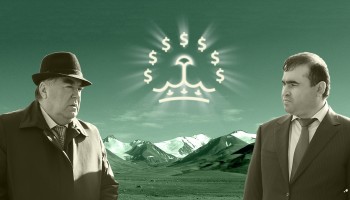

President Rahmon, who has been in office for 27 years, may berate public servants about the country’s budgetary shortfalls — but documents obtained by OCCRP show that his campaign to enforce the rules doesn’t apply to his inner circle.

A March decree exempts three companies — two of which are linked to the president’s family — from paying import duties and value-added tax on many different types of construction materials that can be used to renovate health spas and hotels, including tiles, laminate, and showers.

The companies were given permission to import hundreds of toilets, thousands of tons of steel rebar, and over 10,000 square meters of ceramic floor tile, all duty free. A supplementary decree issued in July grants tax exemptions for another set of items that can be used in later stages of renovation, including furniture and pine trees, for which other companies are required to pay customs fees.

OCCRP reported last year on the sprawling business interests of Shamsullo Sakhibov, who is married to one of President Rahmon’s seven daughters. The investigation exposed how Sakhibov has benefited from his ruling family connections, dominating numerous industries in Tajikistan through the conglomerate Faroz, and squeezing out local competitors.

OCCRP has now uncovered that the Sakhibov clan is also behind two of the companies that just received exemptions to upgrade their resort investments. The decrees demonstrate the extent to which the president’s relatives are afforded special treatment.

Soviet to Swanky

The Zumrad health spa was built in the 1970s on the banks of the Isfara River in northern Tajikistan, a picturesque region that borders Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan. The resort was famous across Central Asia for its mineral water and mud baths.

Today the resort can provide accommodation for 500 clients at a time, charging them $11–$25 per day for use of its facilities. The average monthly income in Tajikistan is about $135, making Zumrad spa hardly accessible to most of the country’s citizens.

In April 2015, the government announced plans to privatize Zumrad and valued the company’s assets at almost $1.1 million. By the end of September, a company called Somon-Sugd had acquired the company’s shares for approximately $950,000 and obtained 600 hectares of surrounding farmland for about $91,000. That company’s beneficial owners are two brothers-in-law to President Rahmon, and the head of the company is Narzullo Sakhibov, brother to the president’s son-in-law.

Narzullo Sakhibov has been deputy director of a government agency since 2014, and as such is prohibited by the country’s anti-corruption laws from having private investments.

Zumrad, which is currently undergoing renovations, is listed on both the March and July decrees as exempt from paying duties on imported construction and decoration materials.

Another historic health spa and resort, Shohambari, was sold in June 2016 for $395,000 to Ruhafzo-2015, also linked to Tajikistan’s first family.

Built in the 1950s, Shohambari resort is nestled into the hills of Hissar, just a 45-minute drive from the capital city. It boasts treatments for gastrointestinal, musculoskeletal, and neurovascular diseases through mineral water baths, bowel cleansing and spa treatments, and accommodates up to 1,000 clients per day, in 500 rooms. Its value at the time of sale is unknown.

The new owner, Ruhafzo-2015, was co-founded by Zainullo Sakhibov, another brother of the president’s son-in-law, and a company called Samoh. It is unclear who is behind Samoh, but as recently as 2016 the company co-founded another entity with Sakhibov called Farahnoz-1.

Like Zumrad, Ruhafzo-2015 is listed on the March and July decrees, receiving exemptions on duties for importing decorative and construction materials for the renovation of Shohambari, which these days is covered in scaffolding.

Mahmadzoir Sakhibov, who is married to the president’s eldest daughter, regularly visits both Zumrad and Shohambari resorts to check on the progress of the renovations, according to employees and news reports. In one set of photos published on President Rahmon’s official website, Mahmadzoir Sakhibov can be seen personally giving a tour of Zumrad to his father-in-law.

A third company, construction firm Dario-2015, is also listed in the tax-exemption decrees, but it is unclear whether it is linked to the first family. The company is building an 11-floor hotel in Danghara district, President Rahmon’s birthplace. He attended the hotel’s groundbreaking ceremony in 2016.

Family Fortune

The first family’s omnipresence in Tajikistan’s economy is well documented. Faroz, the company headed by the president’s powerful son-in-law Shamsullo Sakhibov, dabbles in many industries and receives advantages over its competitors.

For example, in 2015, Faroz purchased land rights to Tajikistan’s only ski resort at a steep discount. At the resort’s unveiling ceremony the following year, President Rahmon praised a “patriotic businessman” for the project, without naming his son-in-law. In 2018, the government introduced a series of tourism-related tax and duty breaks, including for the ski resort.

When Faroz invested more heavily into the driving school business in early 2016, the government shut down nearly two thirds of existing driving schools, citing inadequate instruction quality. Those schools that remained on the market were required to operate using autodromes owned by Faroz.

Faroz and its affiliate also received the only licenses in the country to harvest, process, and export asafetida, the gum resin of the ferula plant used in cooking and traditional medicine. Prior to a 2008 presidential decree banning the activity, many poor Tajiks earned a living by collecting the naturally growing plant and extracting its resin to sell abroad.

At the end of August, in a letter to Tajikistan’s government and the country’s Tax Committee, Faroz CEO Azamat Kosimov announced plans to dissolve the company, citing financial insolvency. But some experts suspect the company is simply being restructured following negative attention.

In addition to their investments in Tajikistan’s winter sports, driving schools, and medicinal plants — as well as banking, mining, customs terminals, and more — President Rahmon’s relatives can now count both Zumrad and Shohambari health spas among their sprawling business interests.

They can also thank the government for tax breaks on products used to upgrade the resorts.